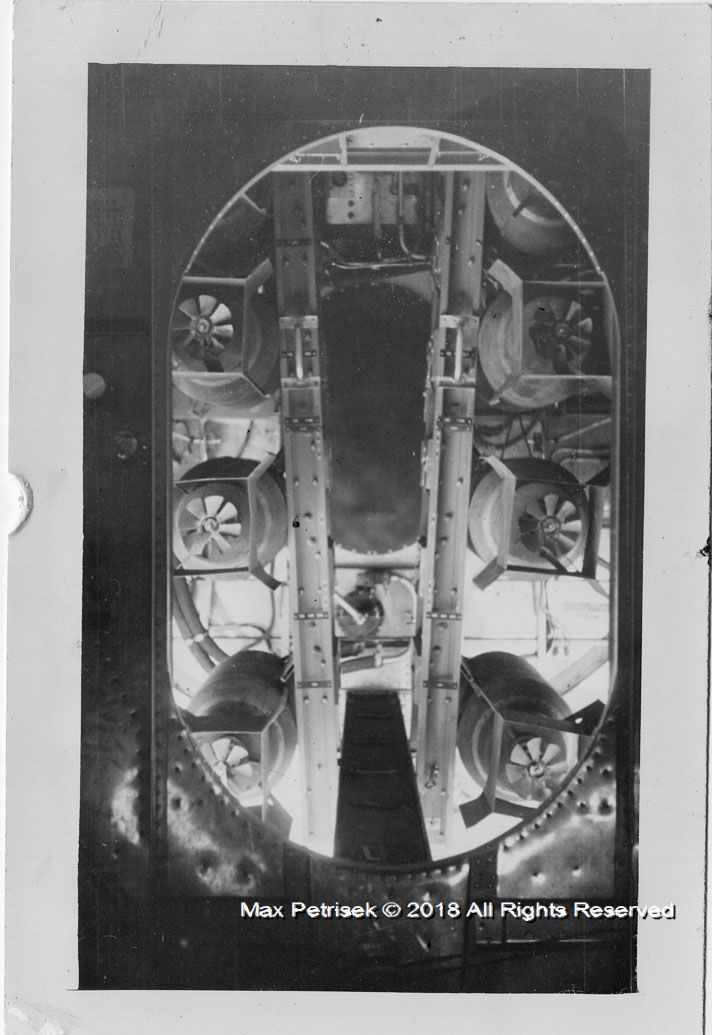

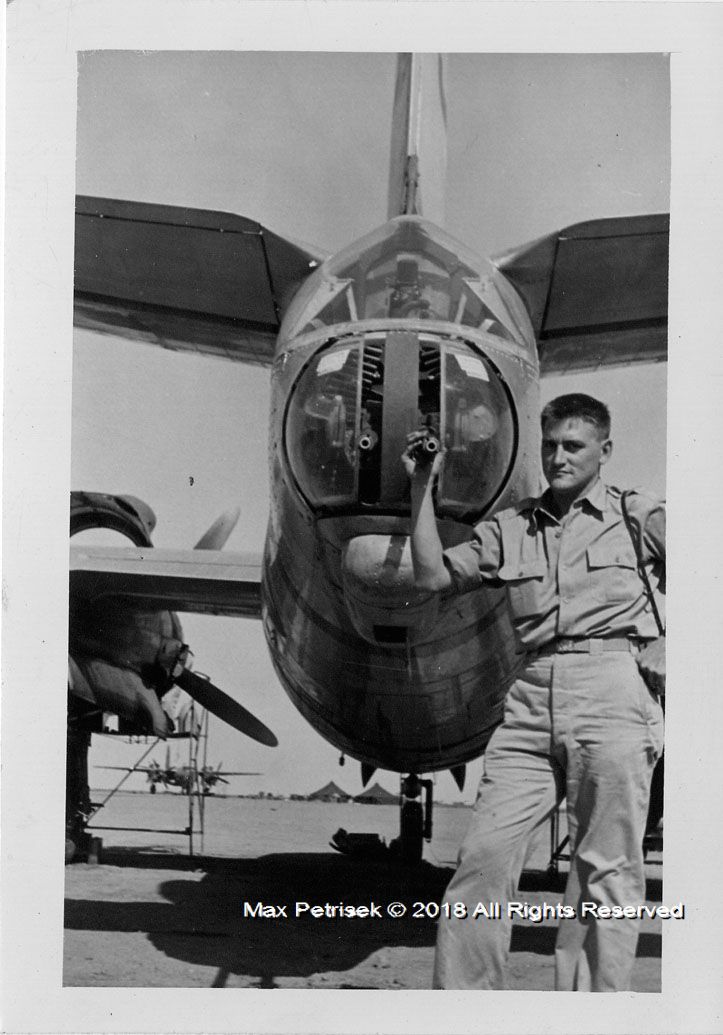

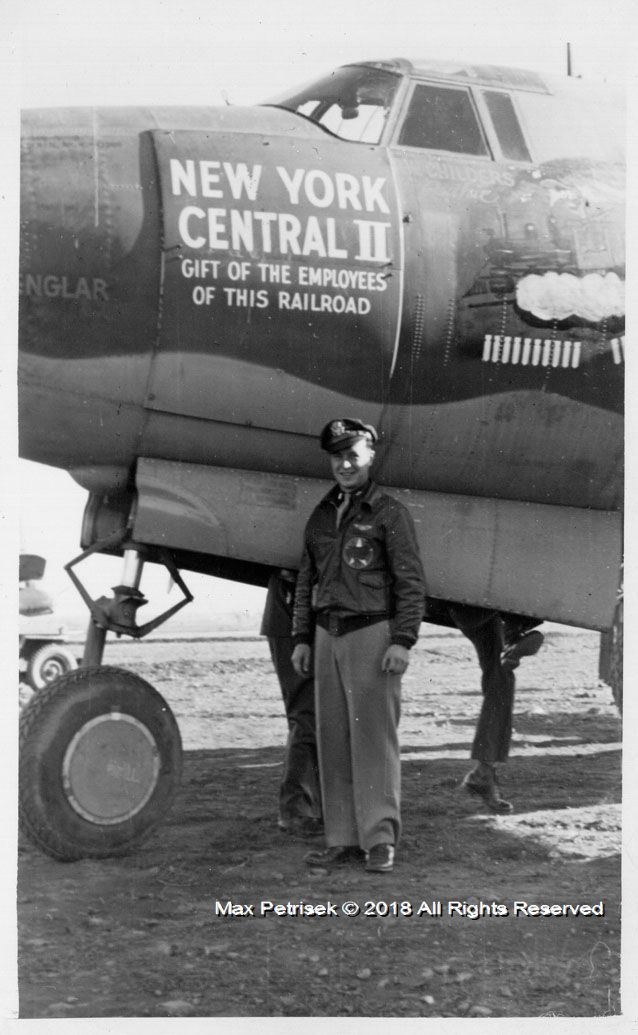

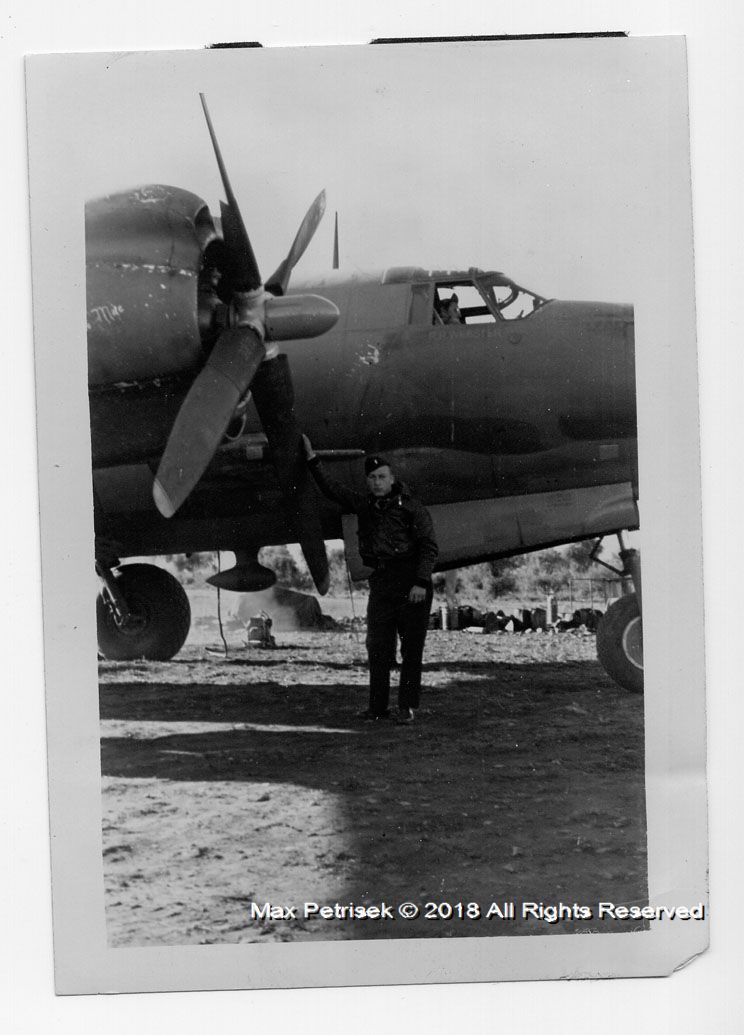

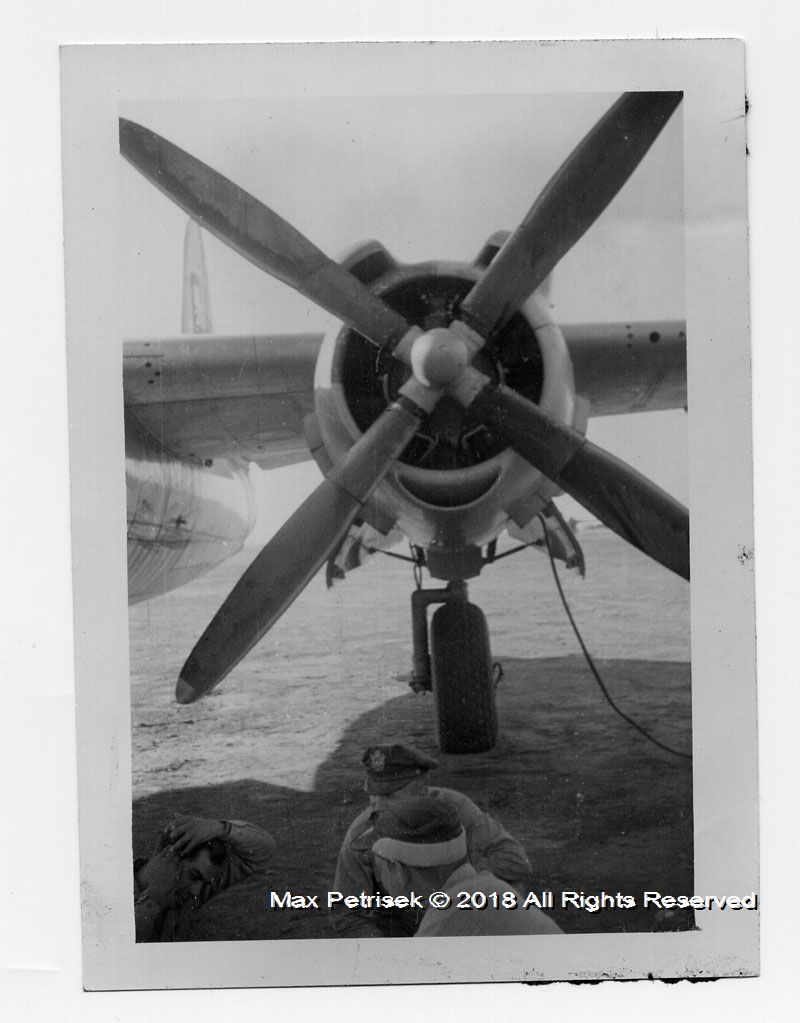

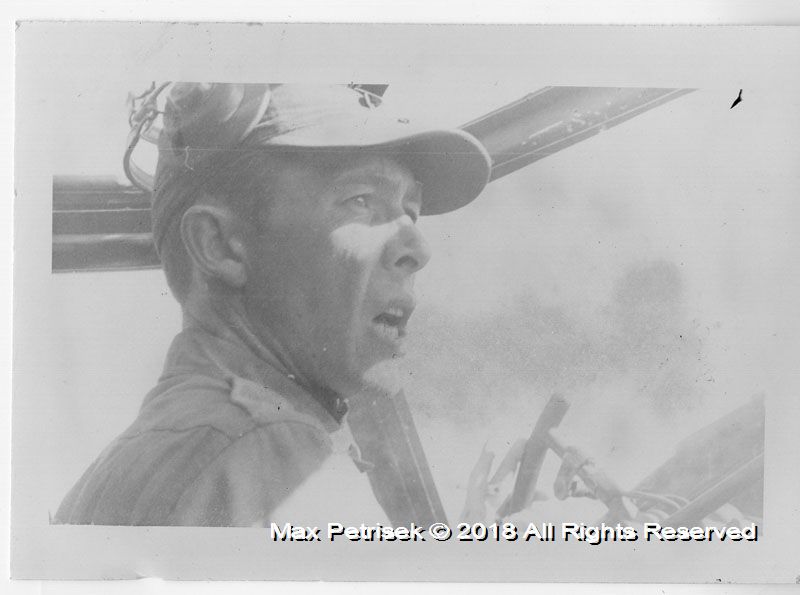

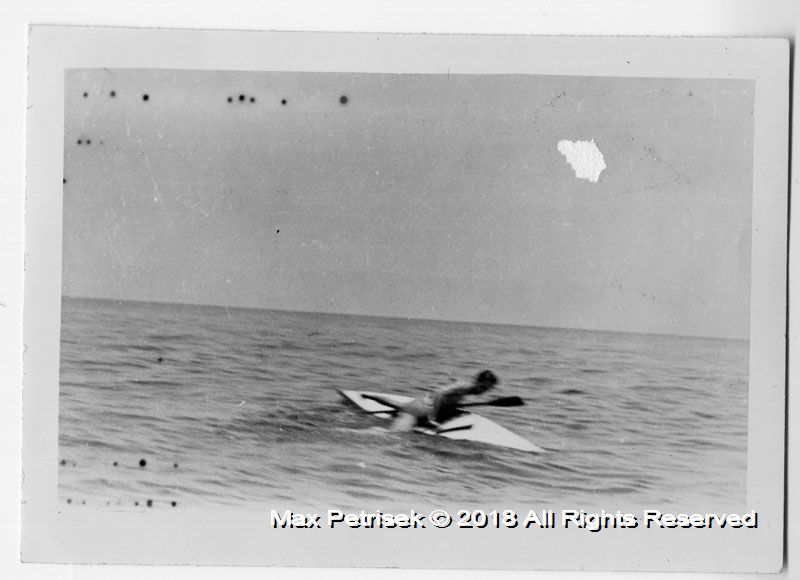

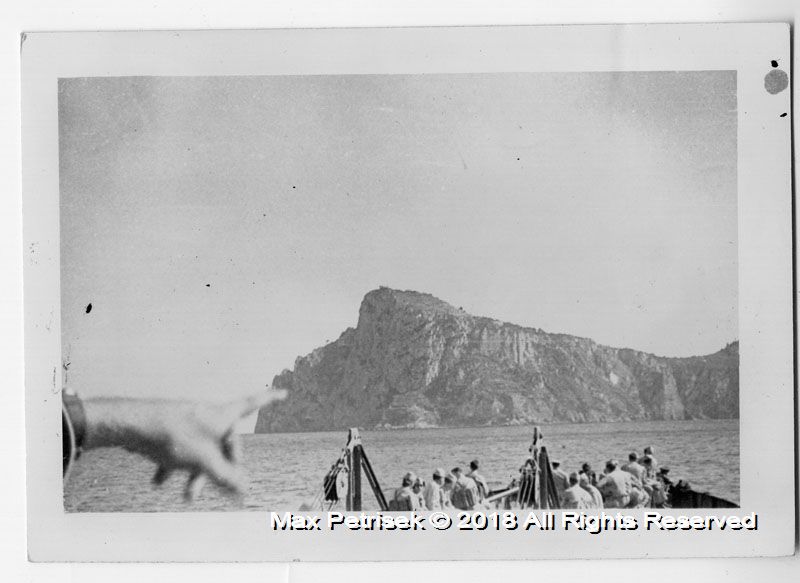

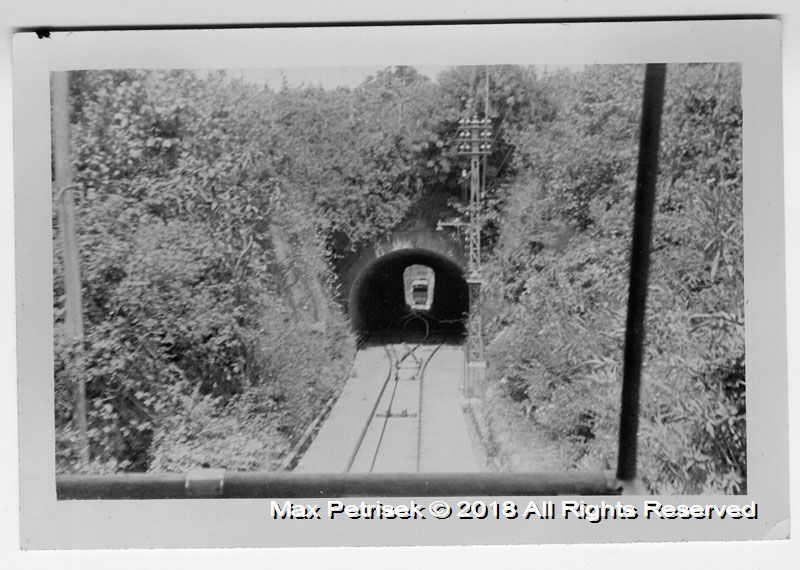

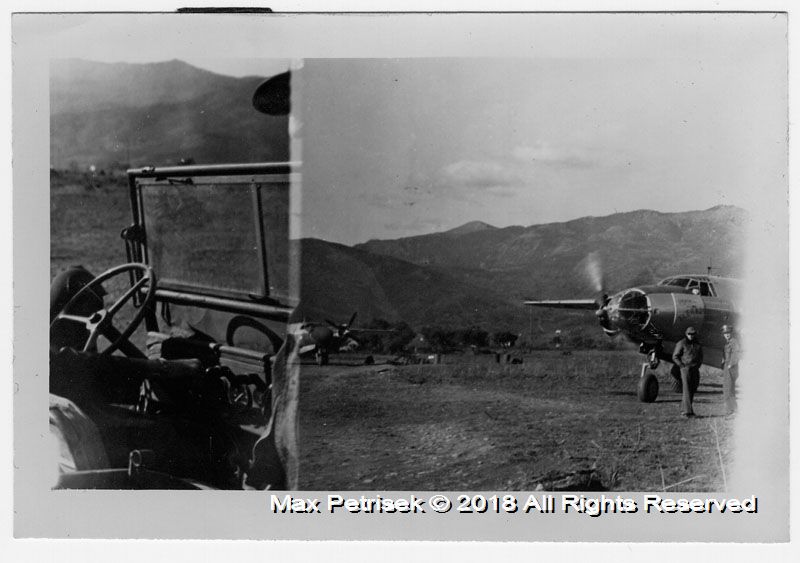

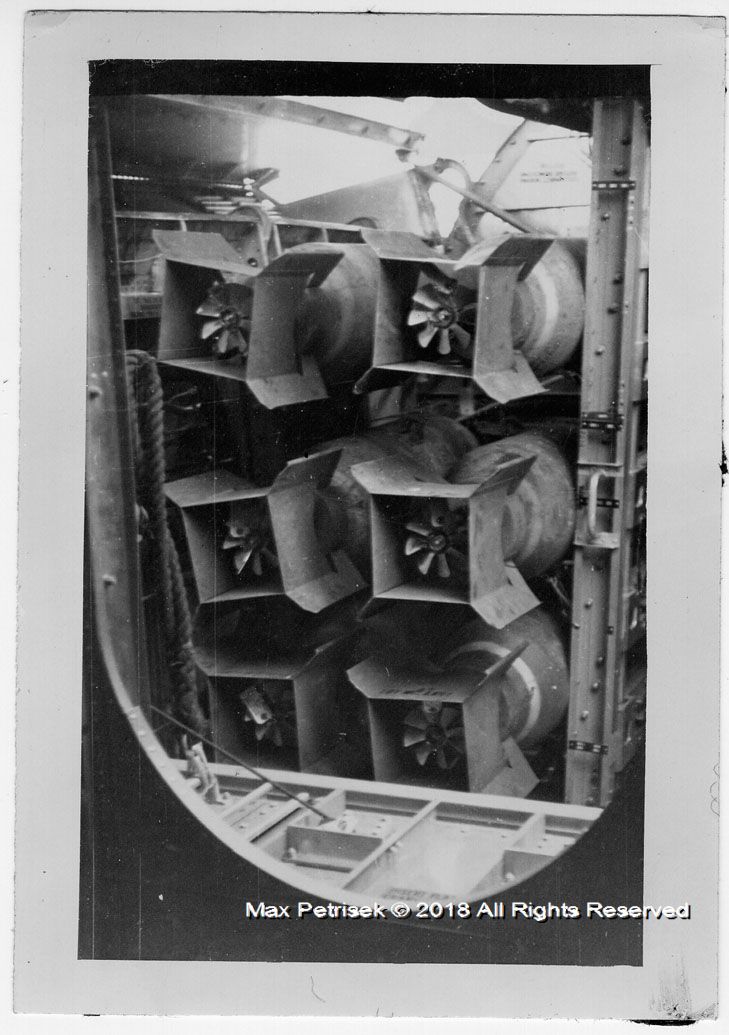

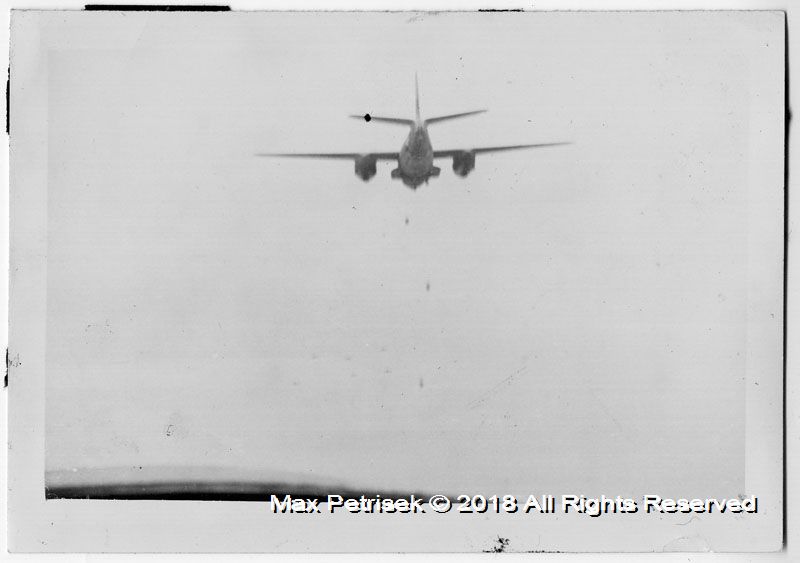

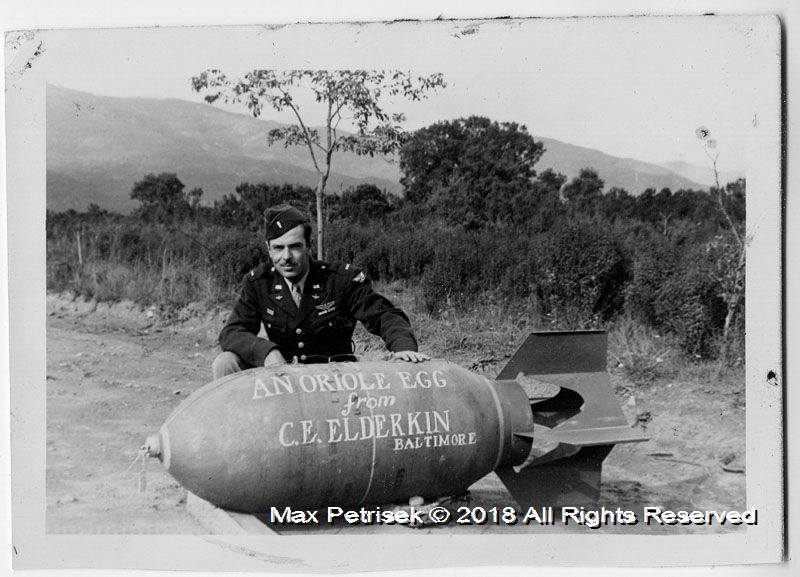

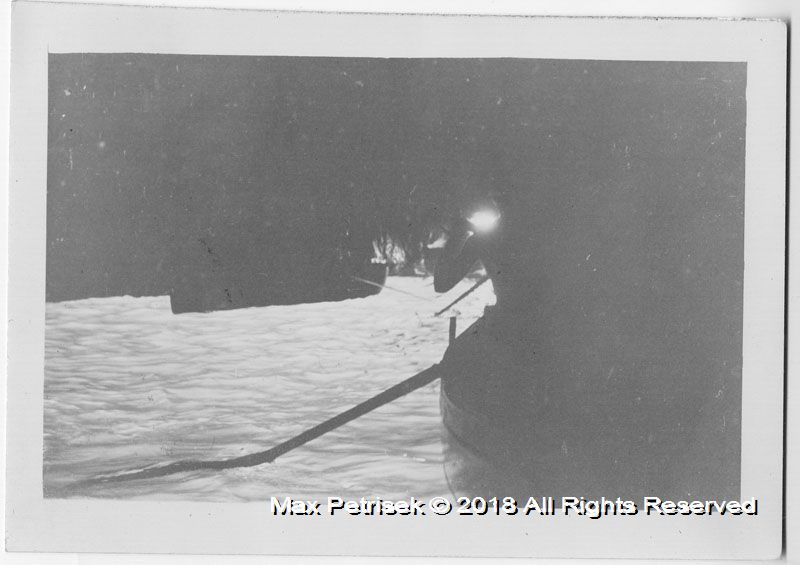

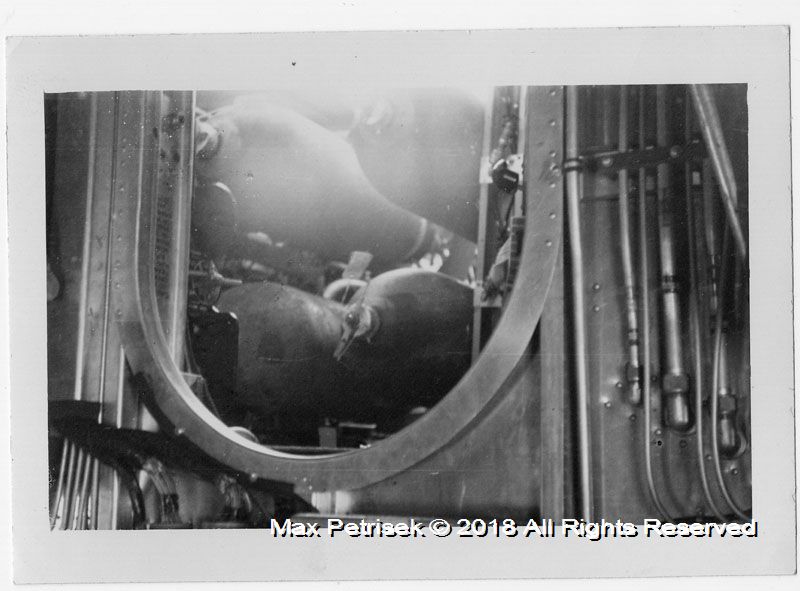

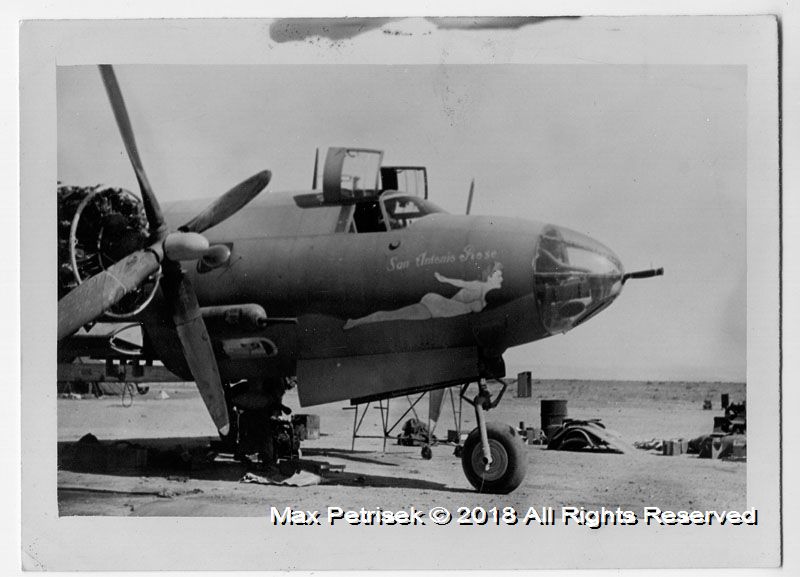

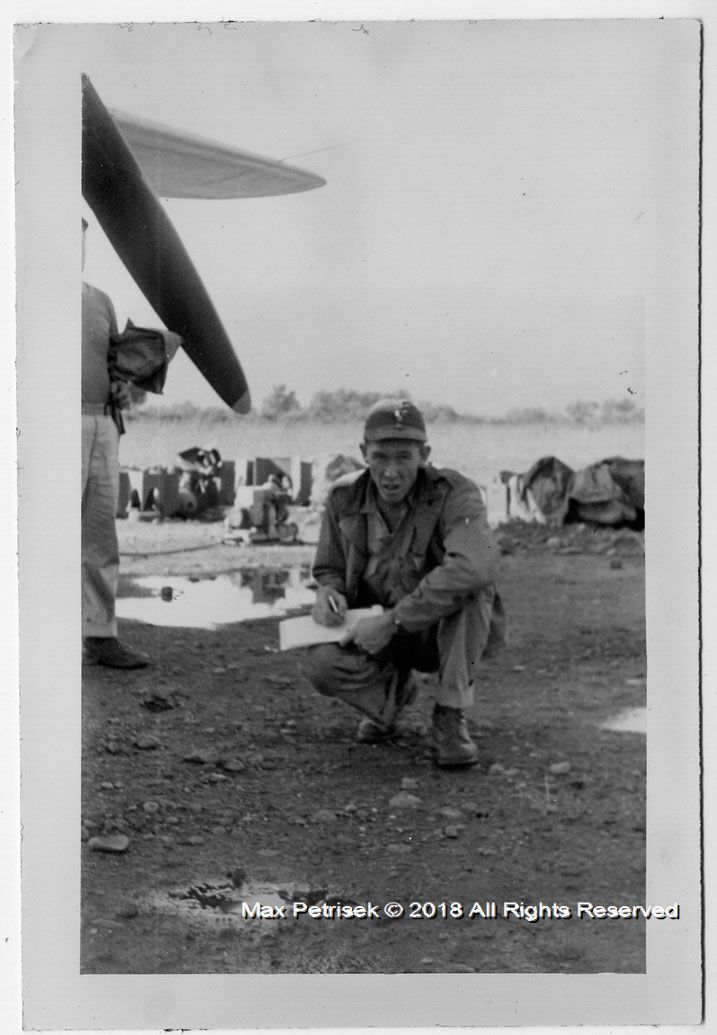

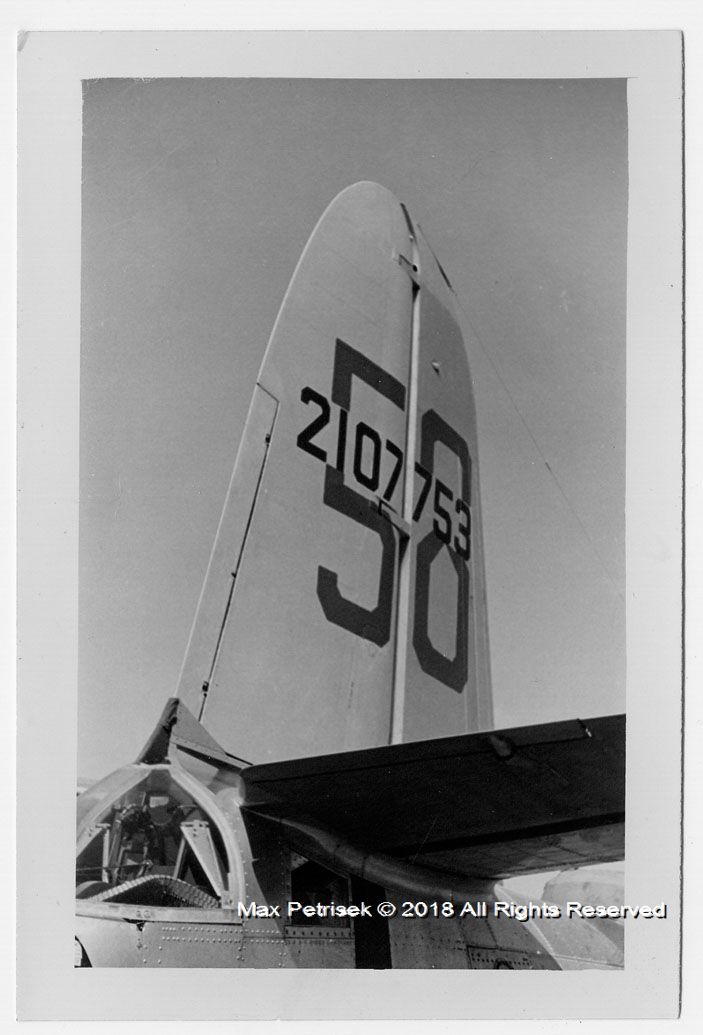

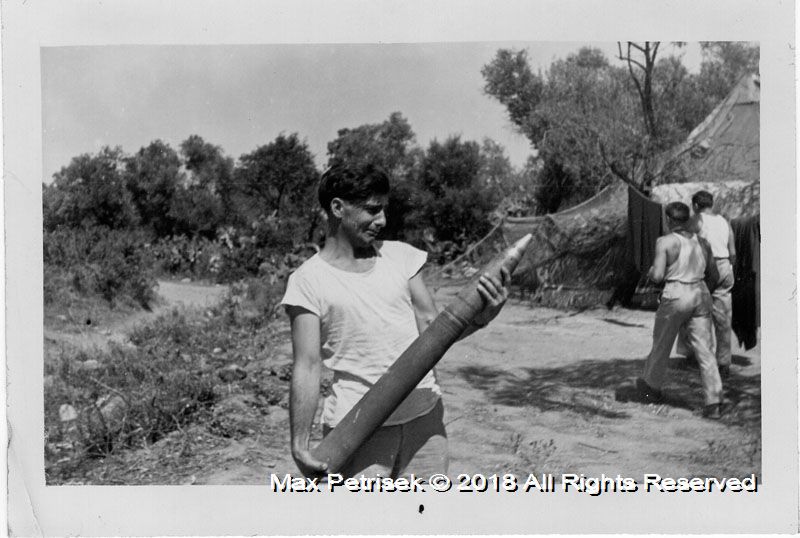

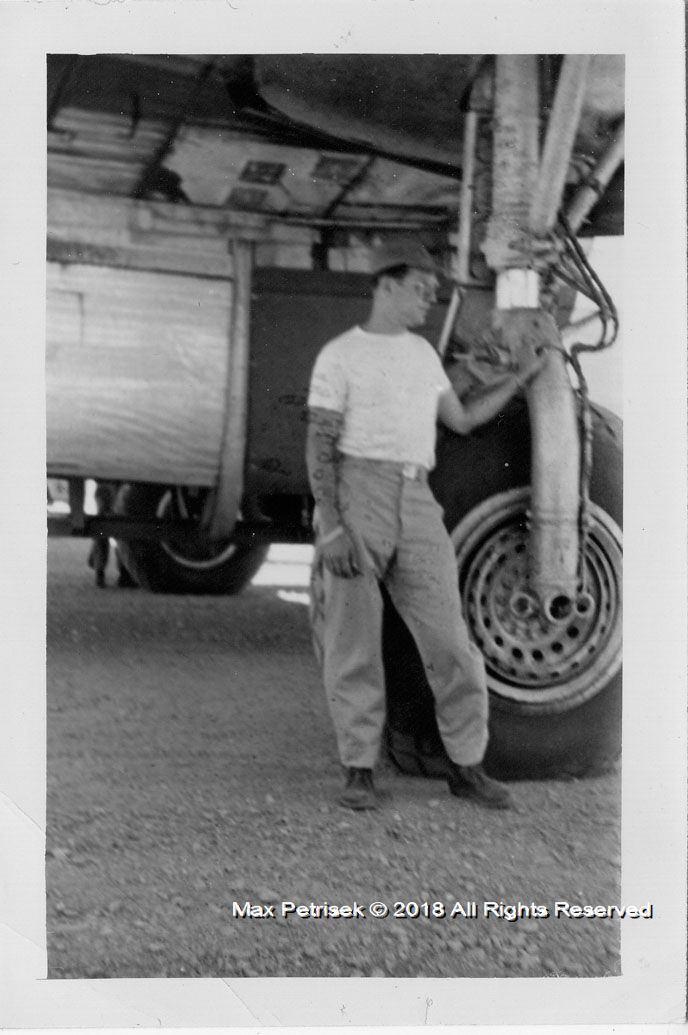

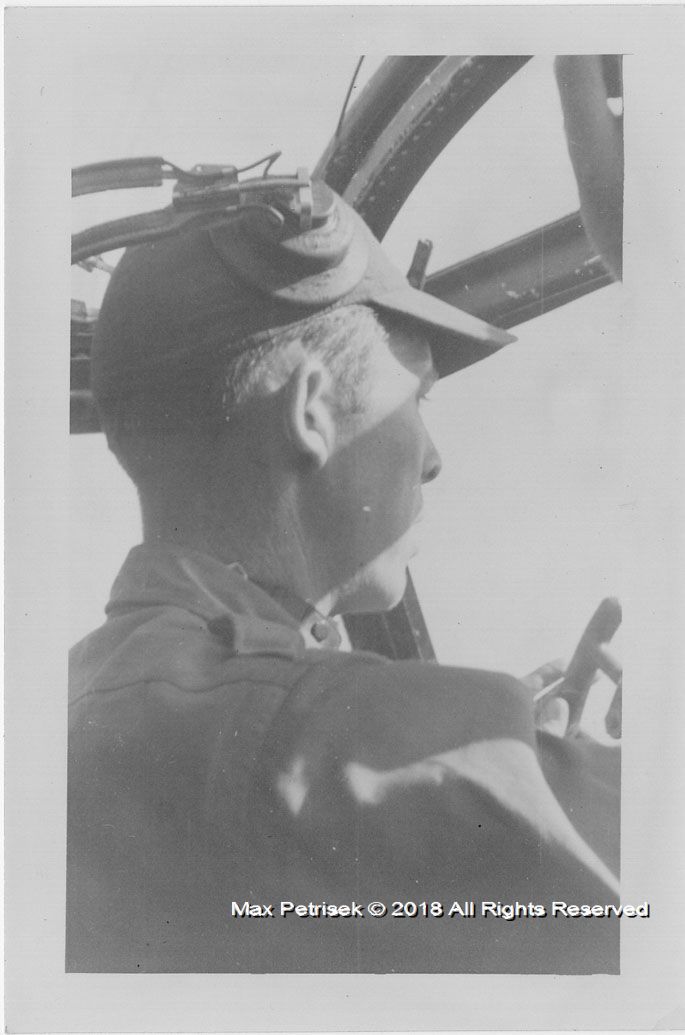

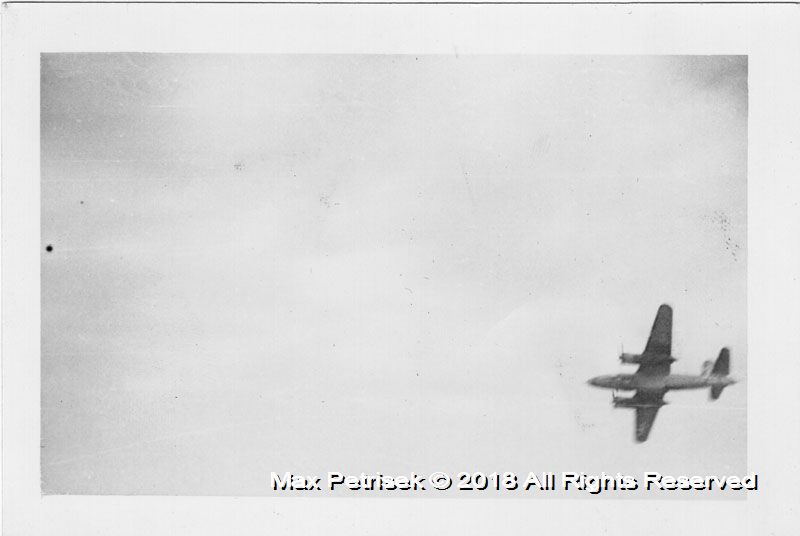

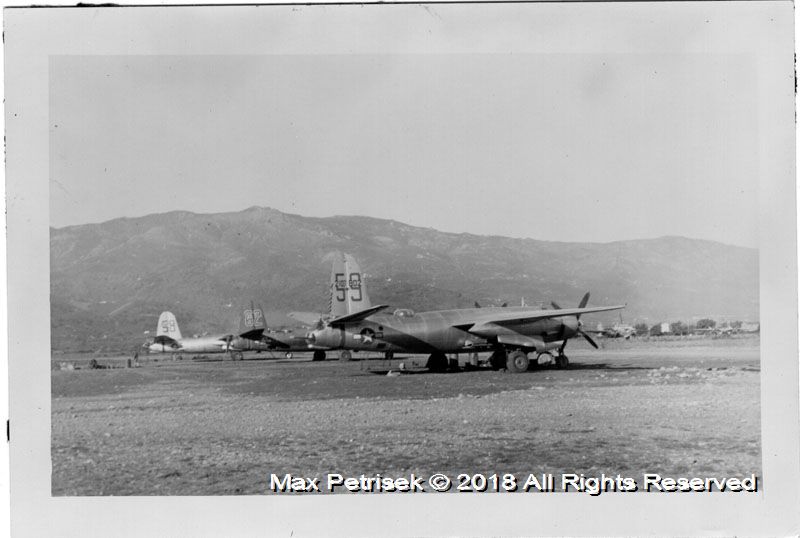

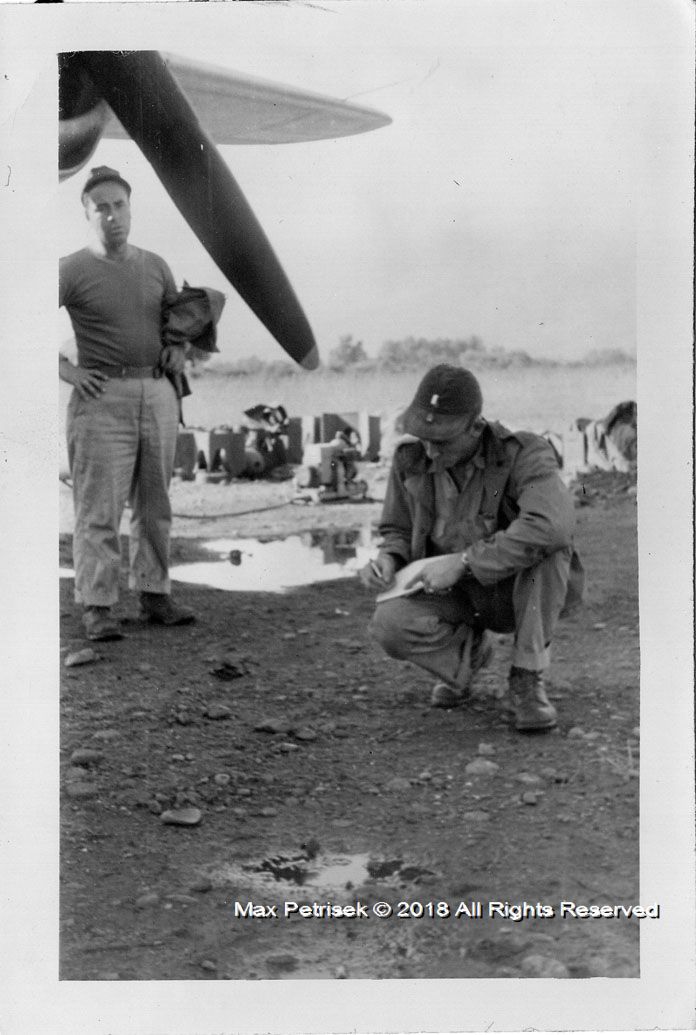

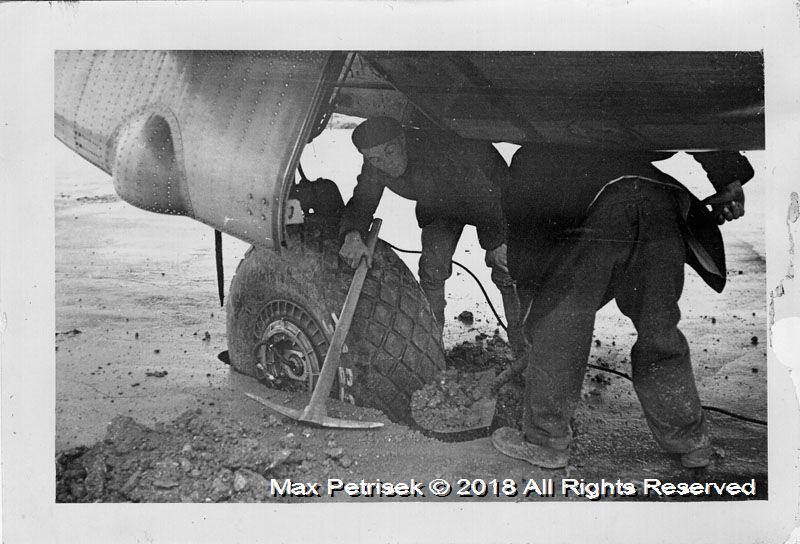

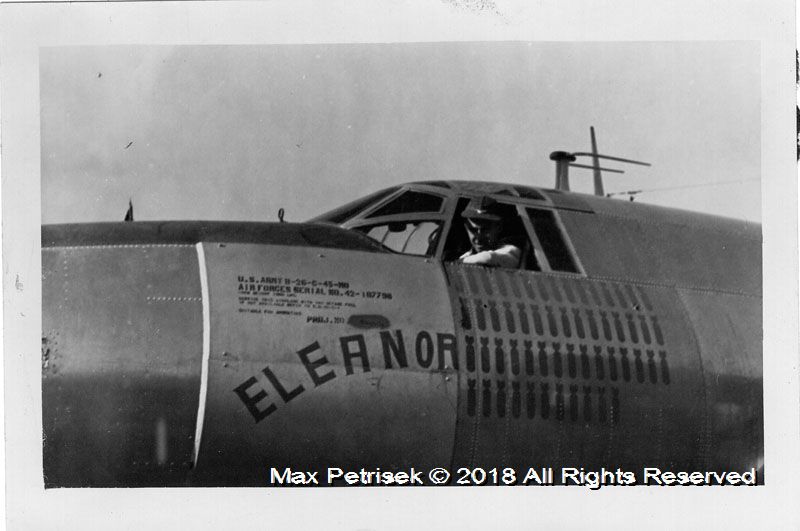

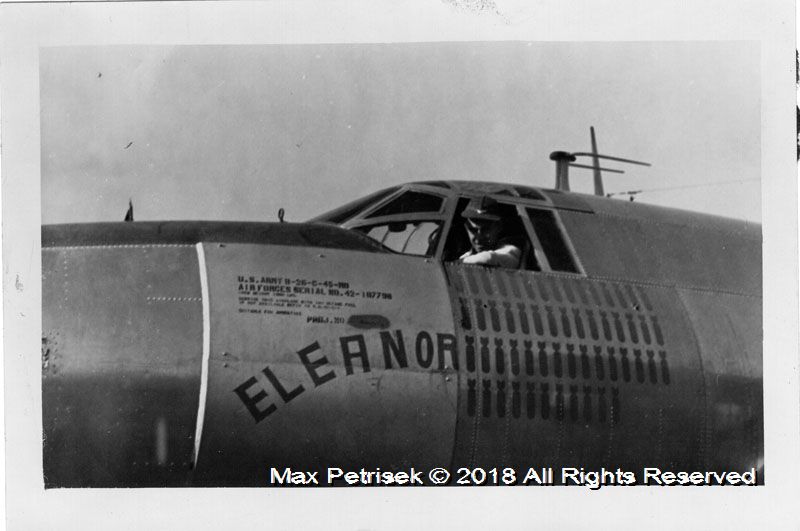

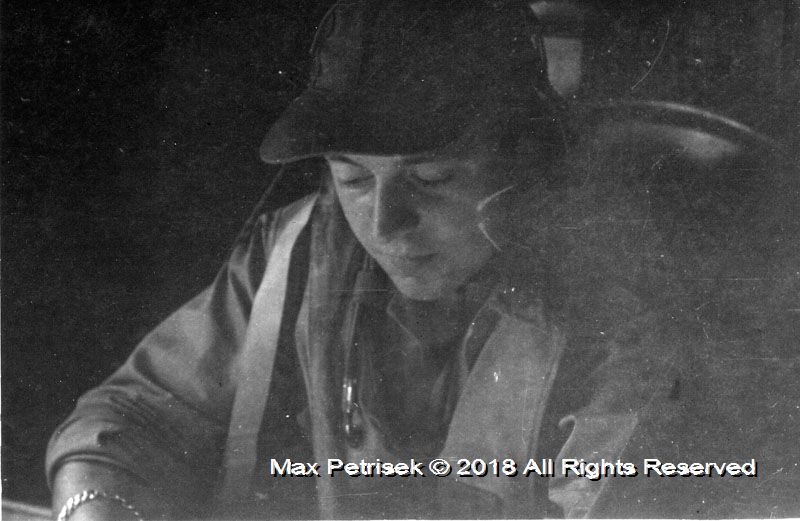

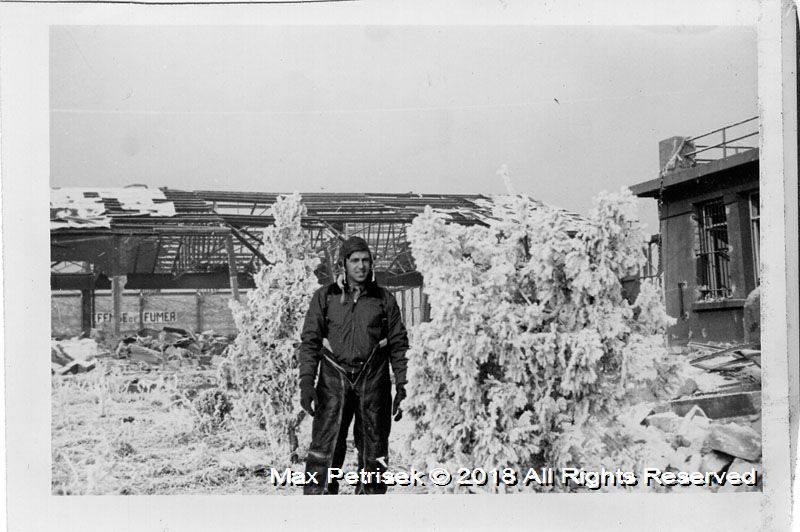

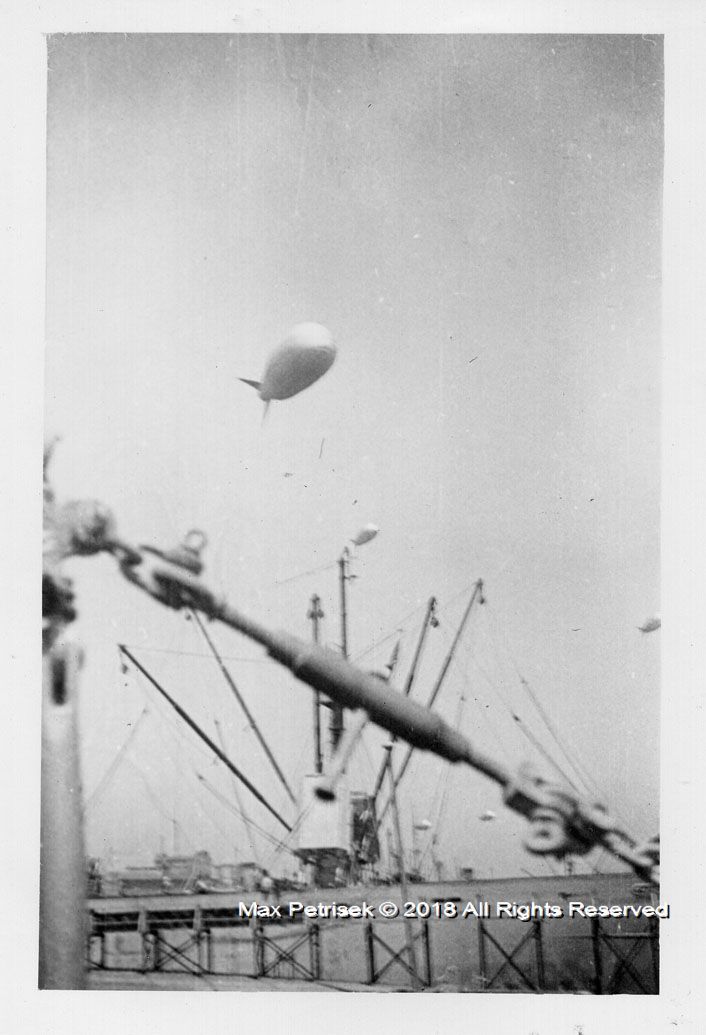

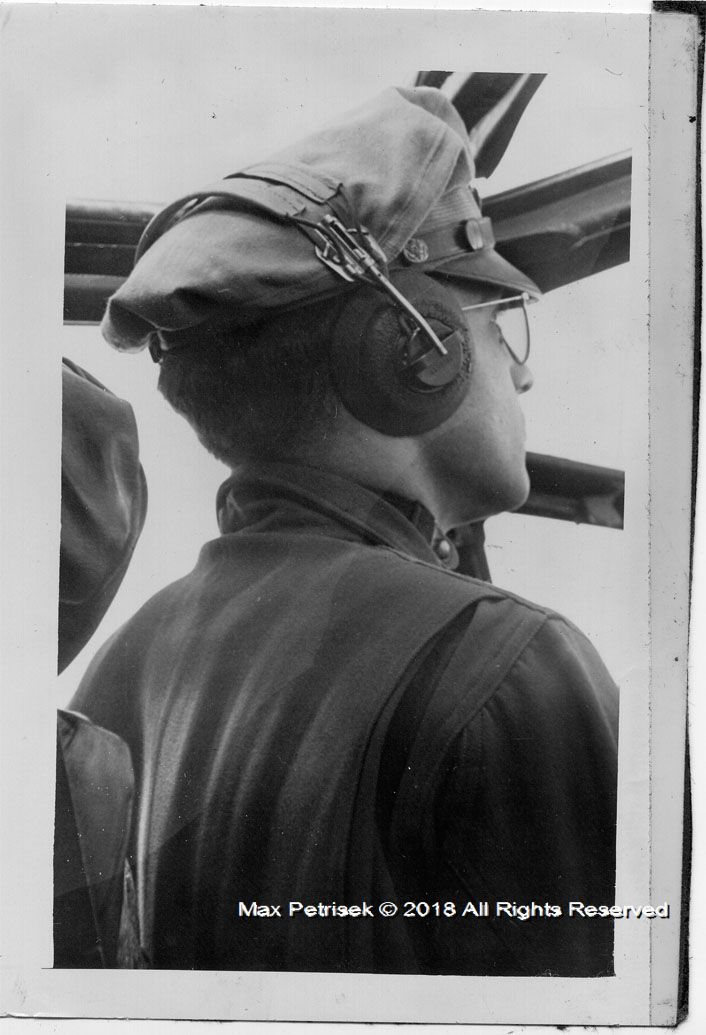

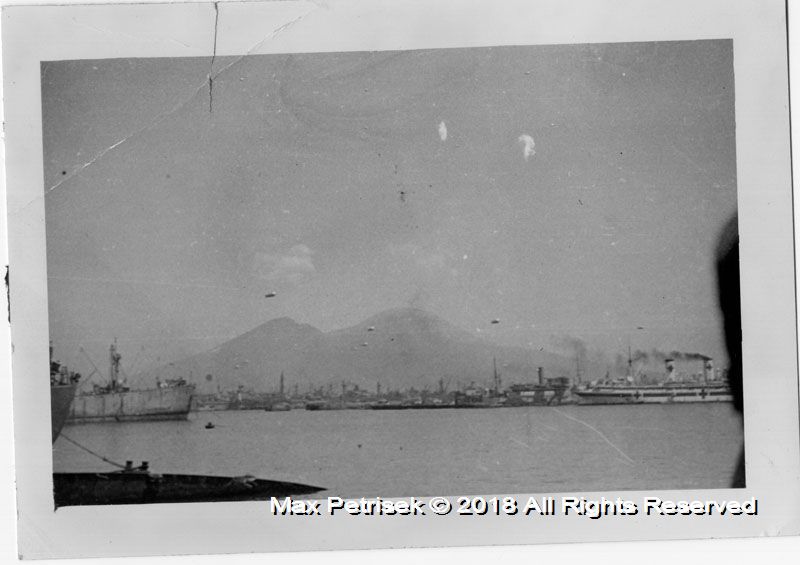

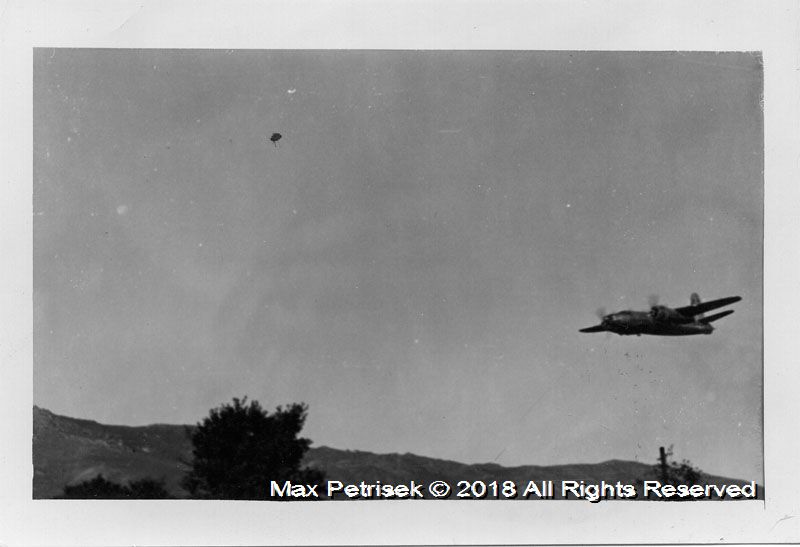

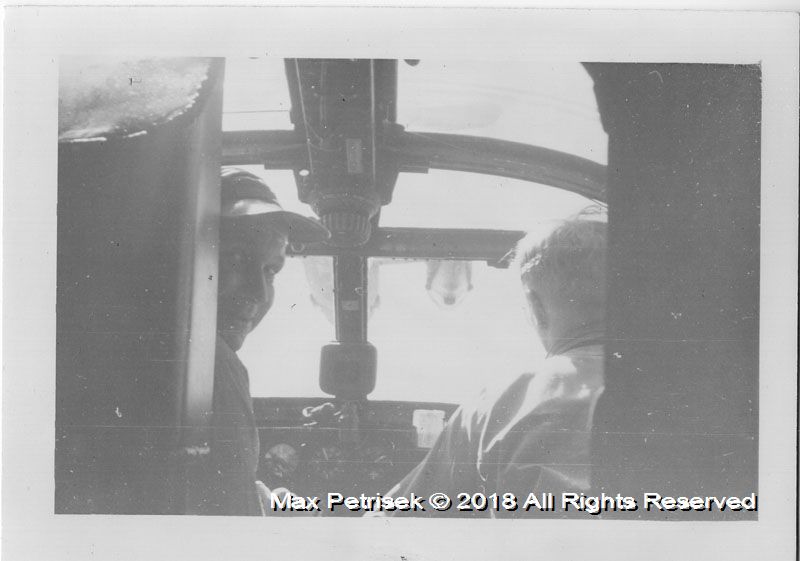

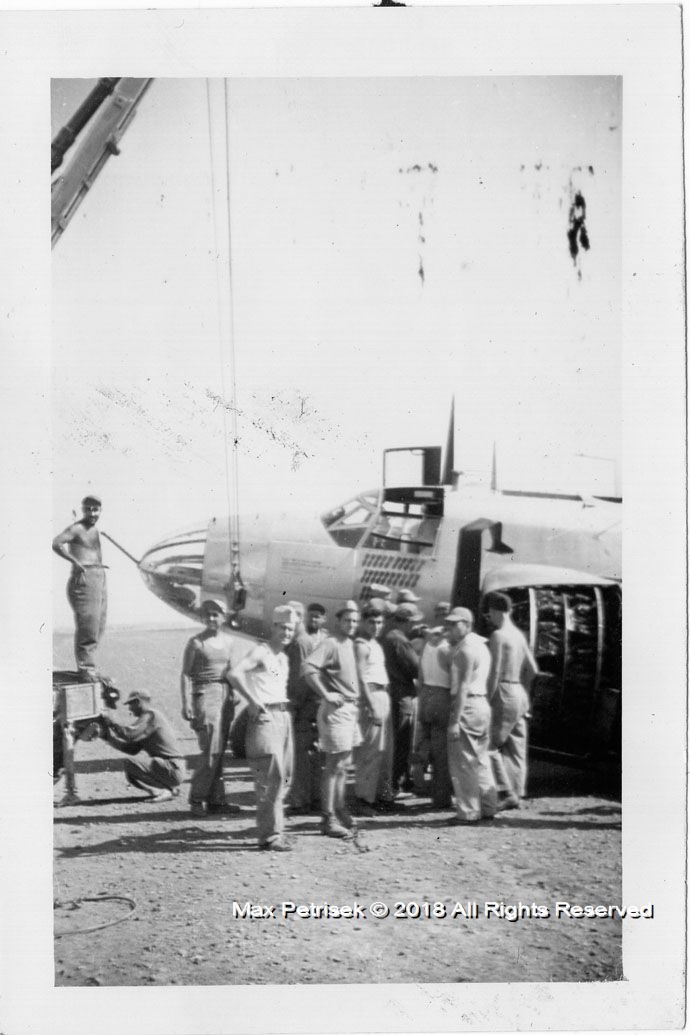

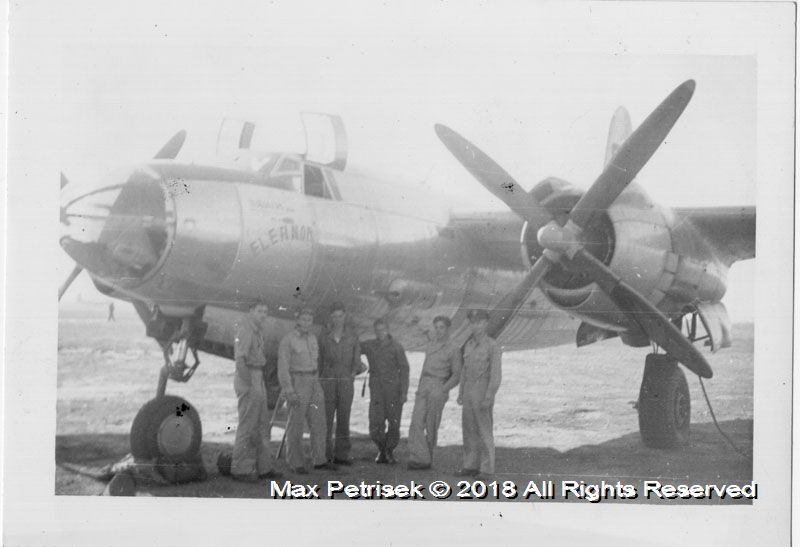

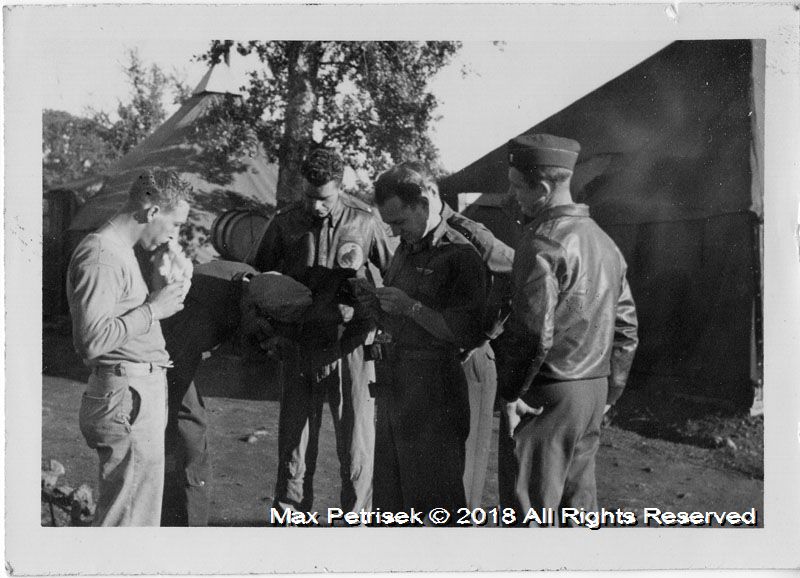

- "While on a mission to bomb the Rovereto railroad bridge, the B26

piloted by Capt Max Petrisek and crew was hit by a flak shell just

behind the bomb bay. It did not explode on impact but exited above the

rear gunners position and exploded there killing the tail gunner, Sgt

Gunnels, and severely damaging the stabilizer controls. Capt Petrisek

landed at a British airfield near Ancona. Sadly, this was Sgt. Gunnels

last combat mission prior to returning to the USA." Trevor Allen,

historian B26.com

-

-

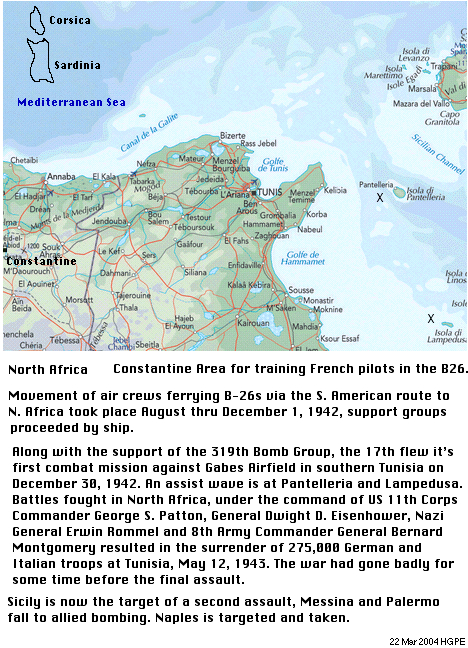

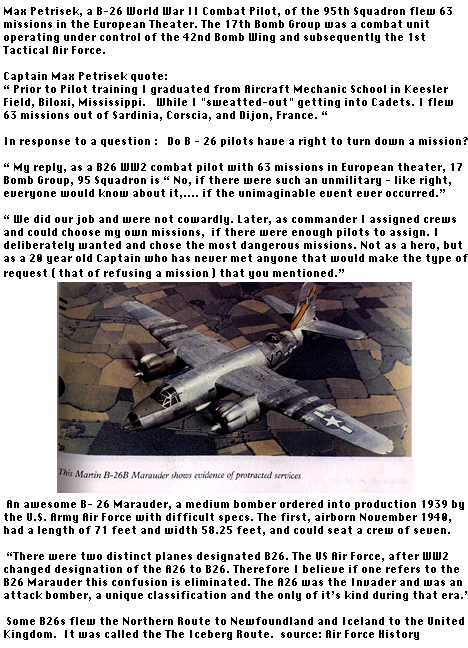

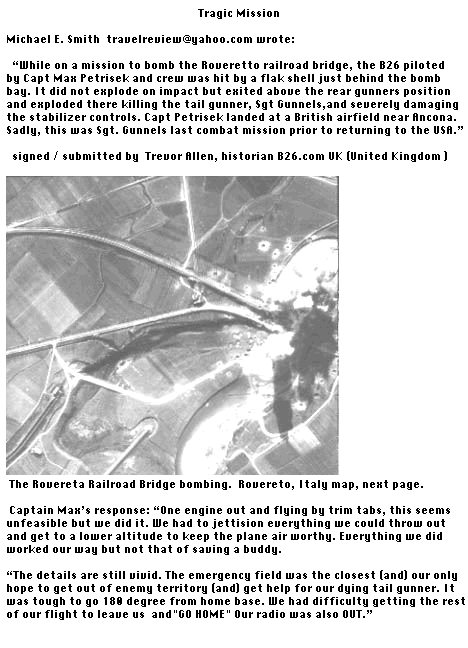

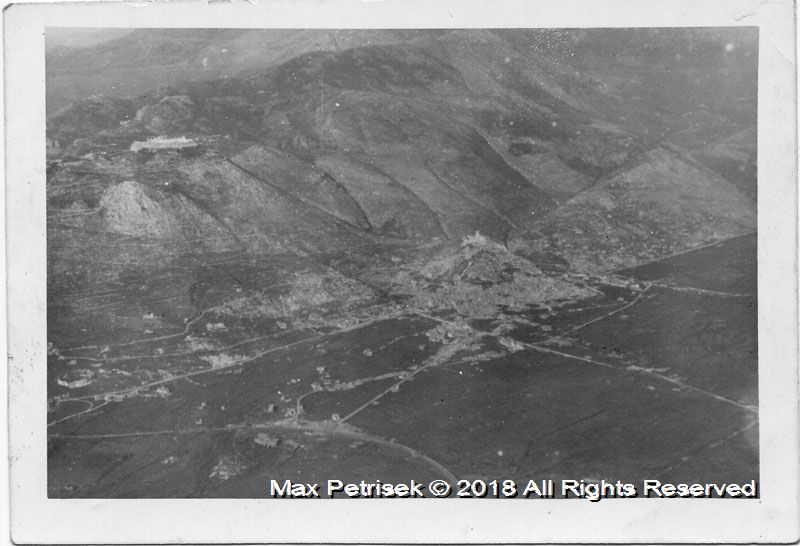

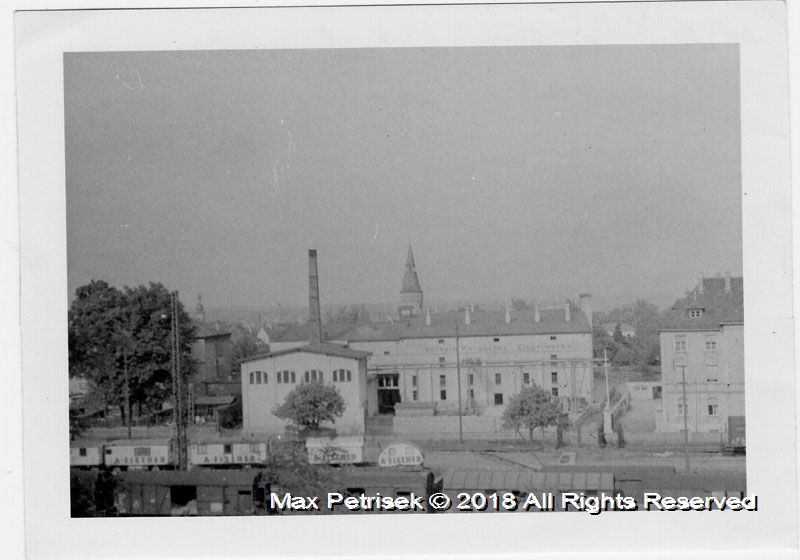

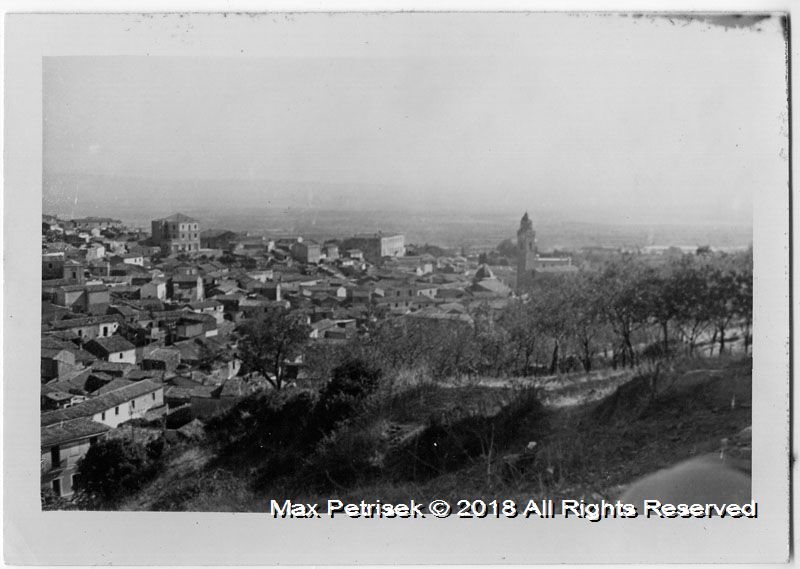

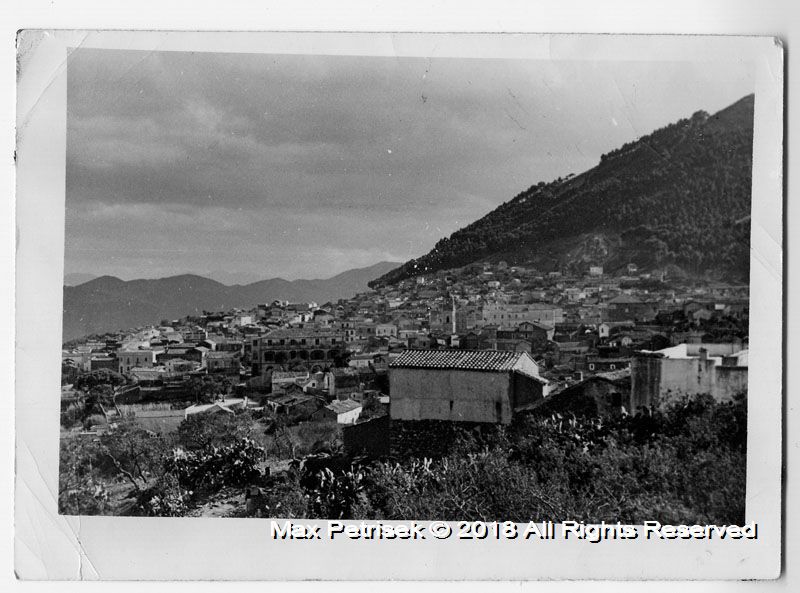

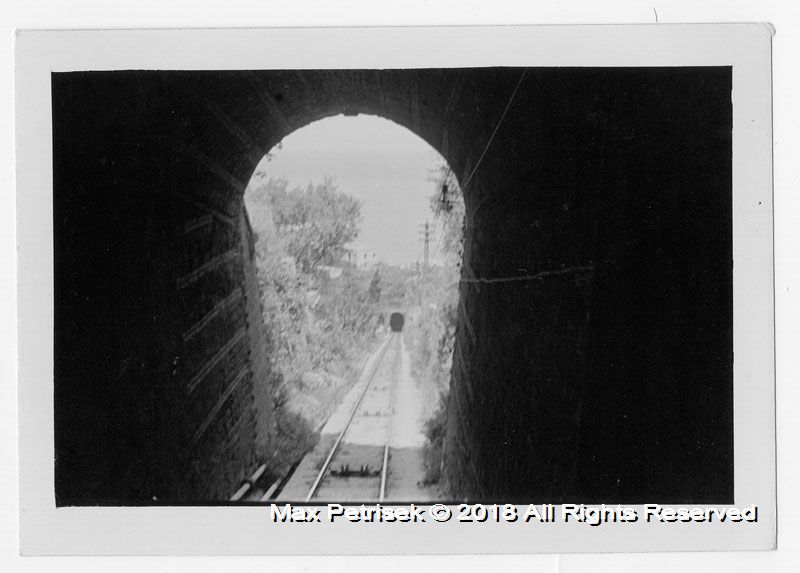

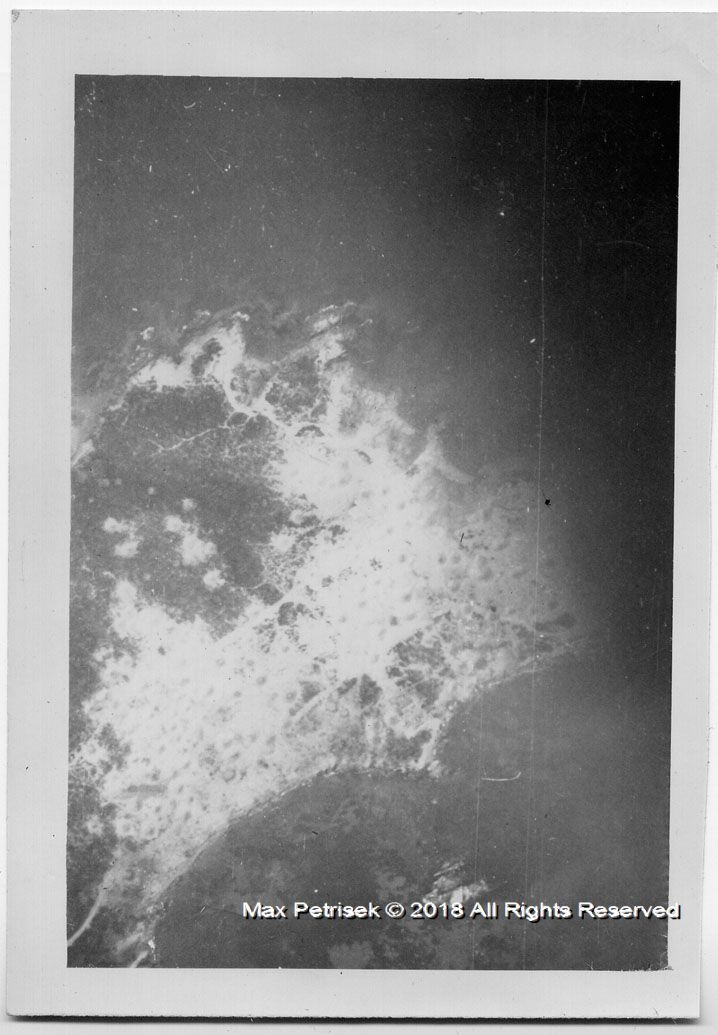

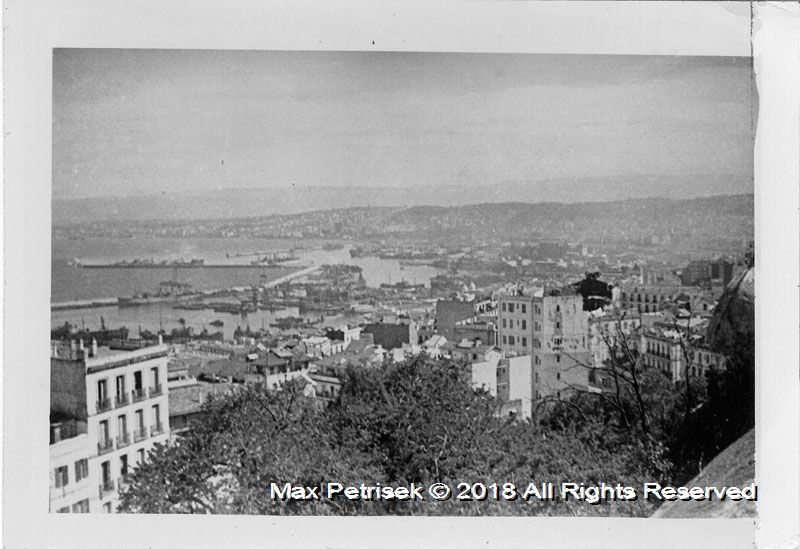

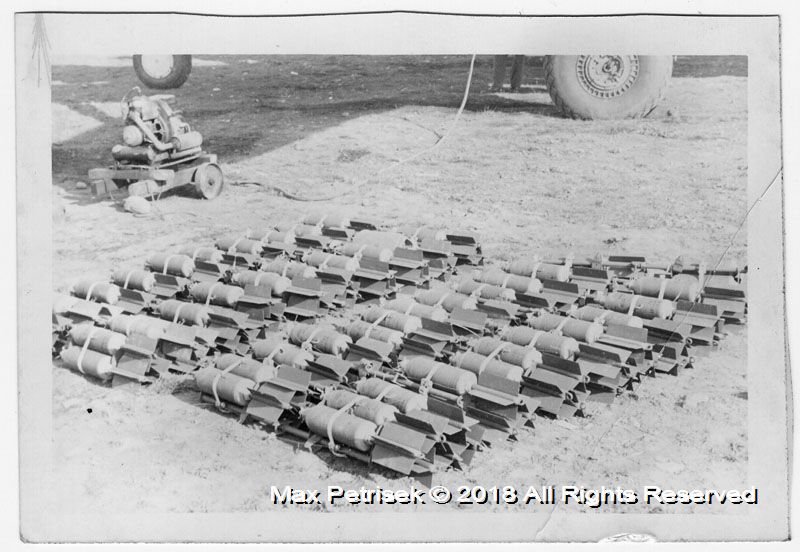

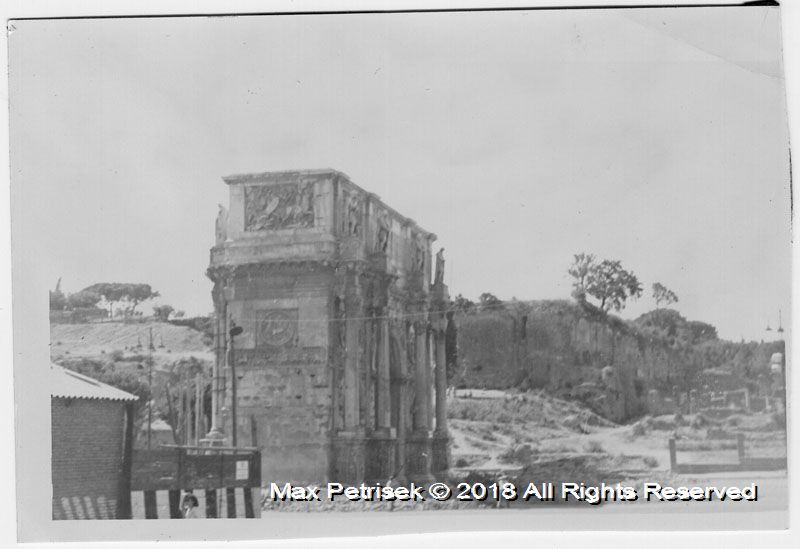

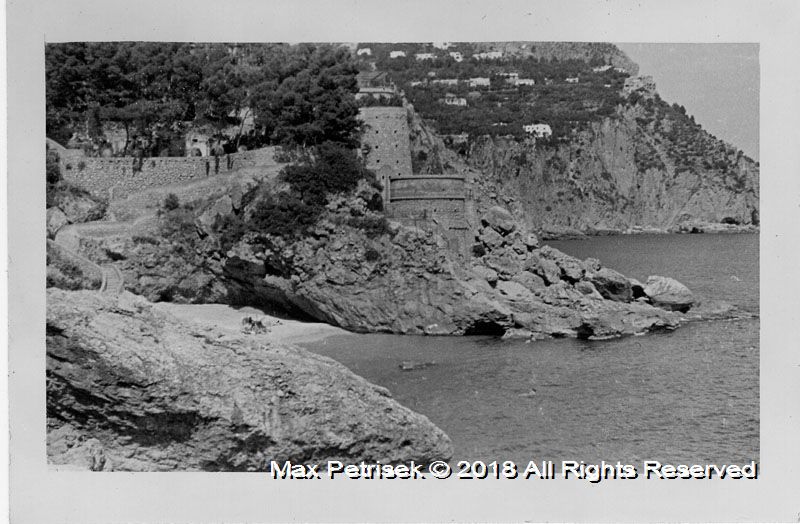

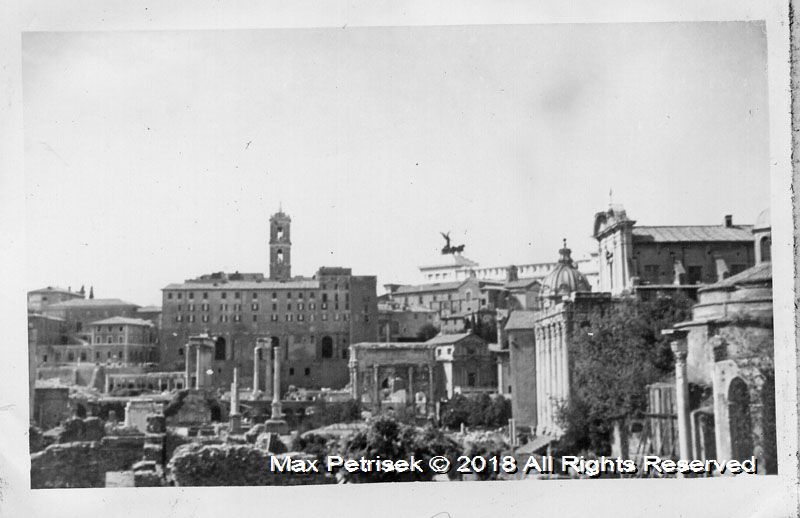

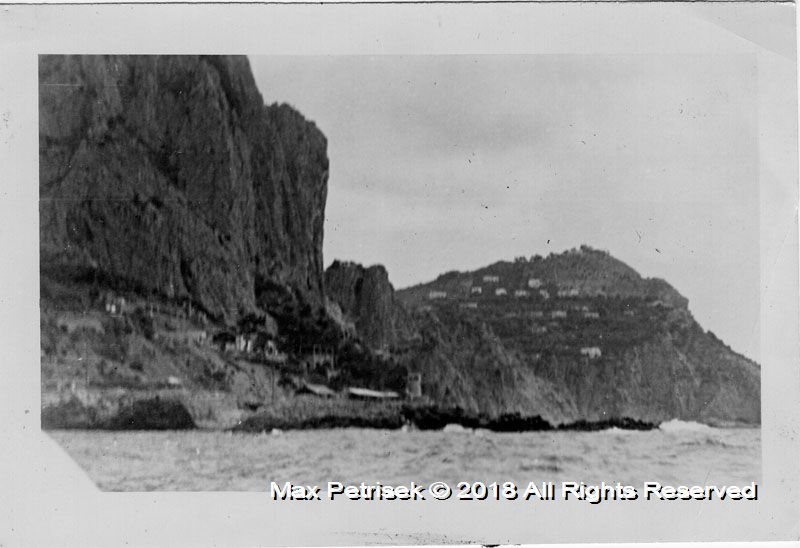

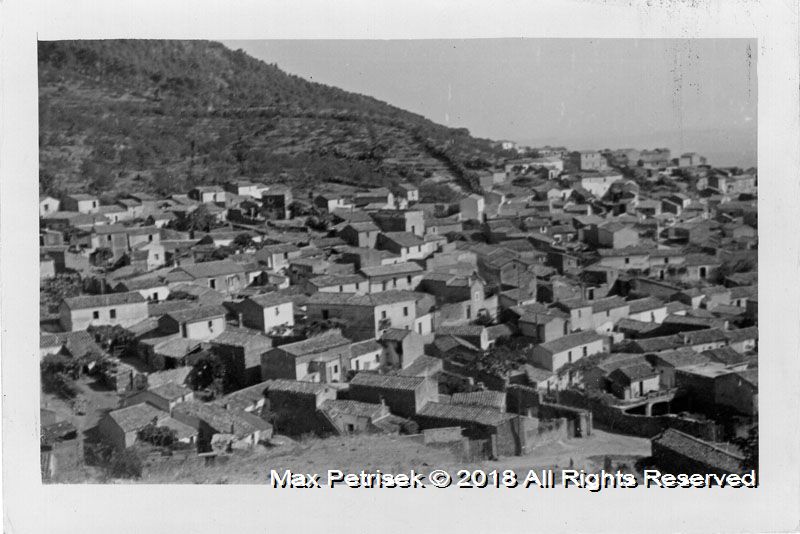

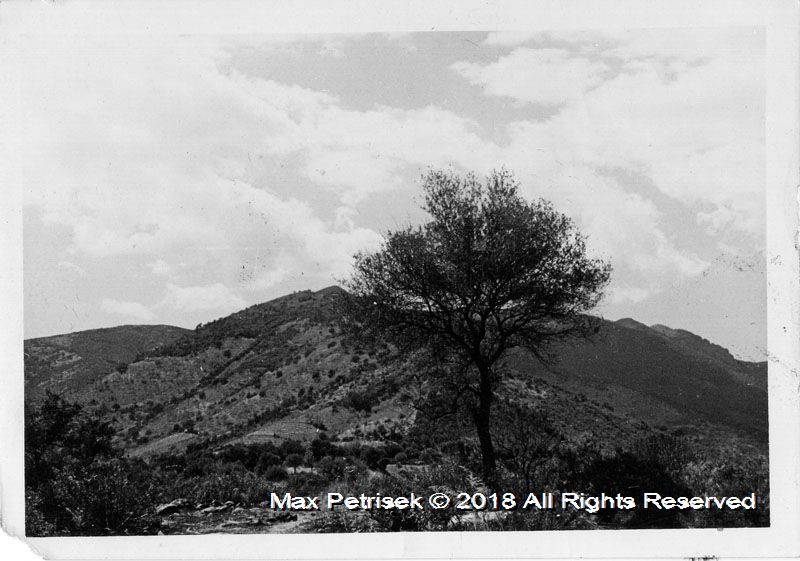

- The Rovereto Railroad Bridge bombing. Roveretto Italy map.

-

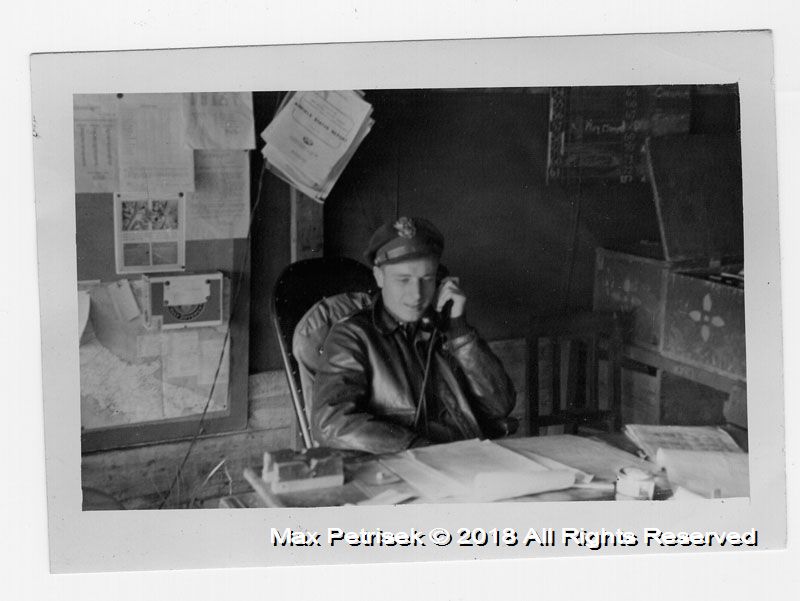

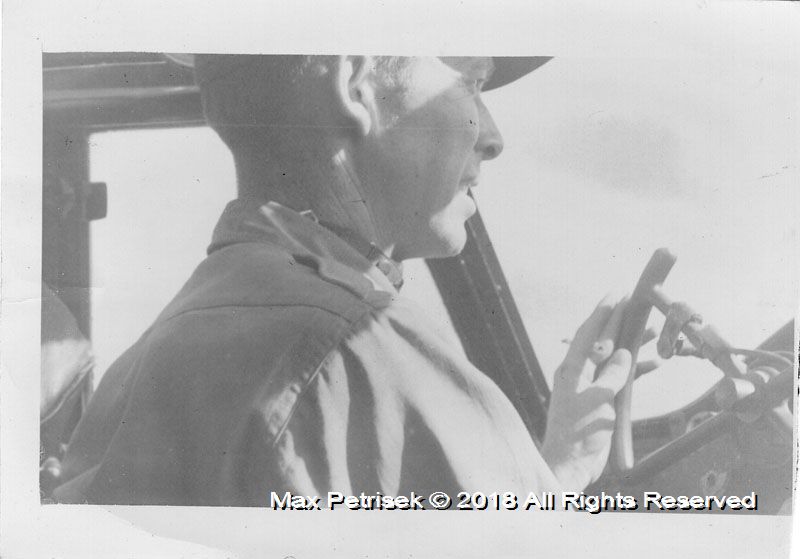

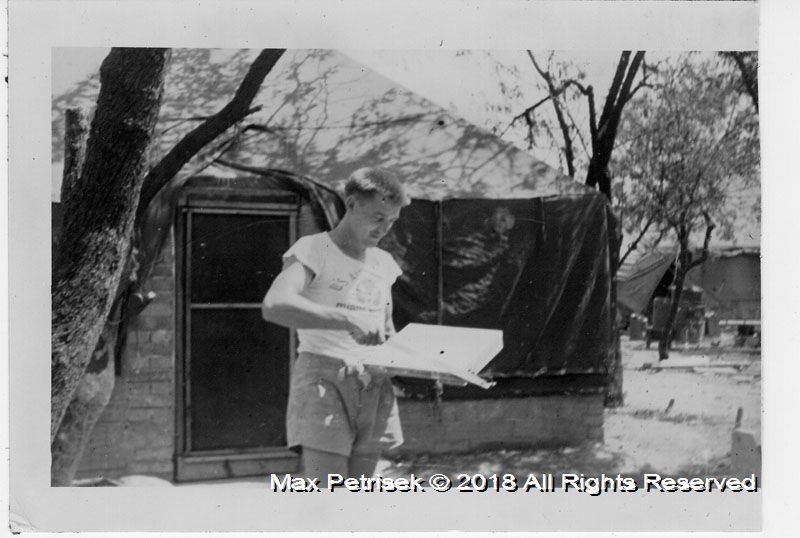

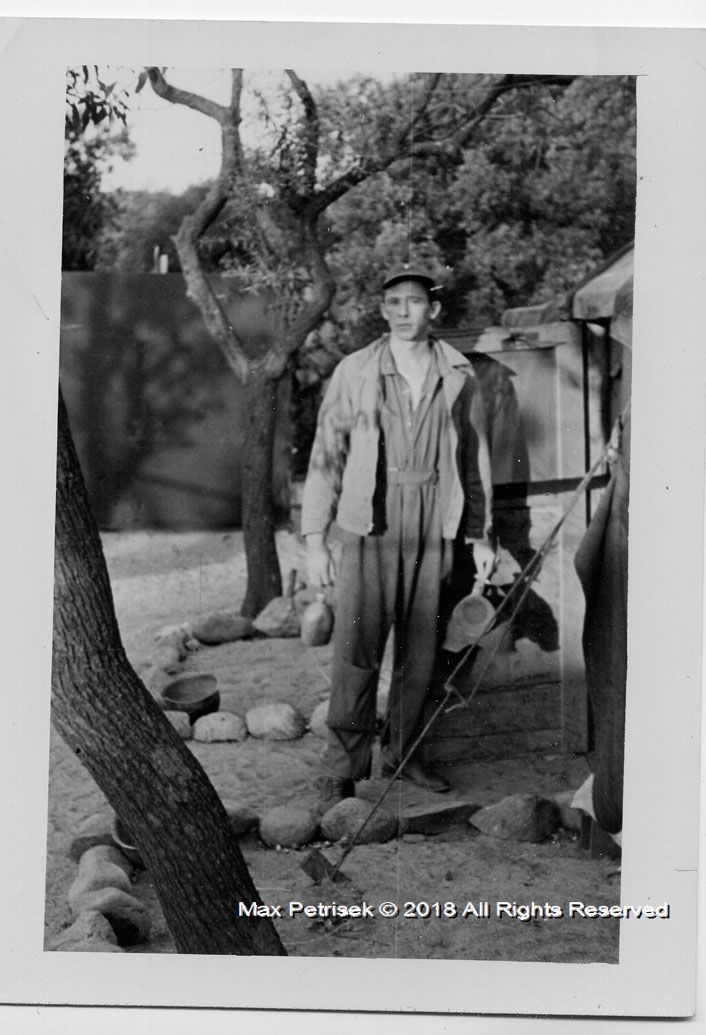

- Captain Max's response: "One engine out and flying by trim tabs,

this seems unfeasible but we did it. We had to jettison everything we

could throw out and get to a lower altitude to keep the plane air

worthy. Everything we did worked our way but not that of saving a buddy.

-

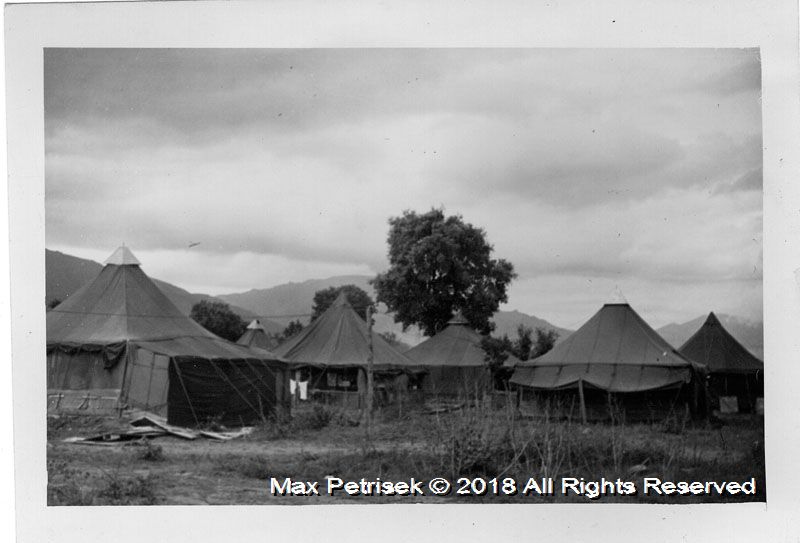

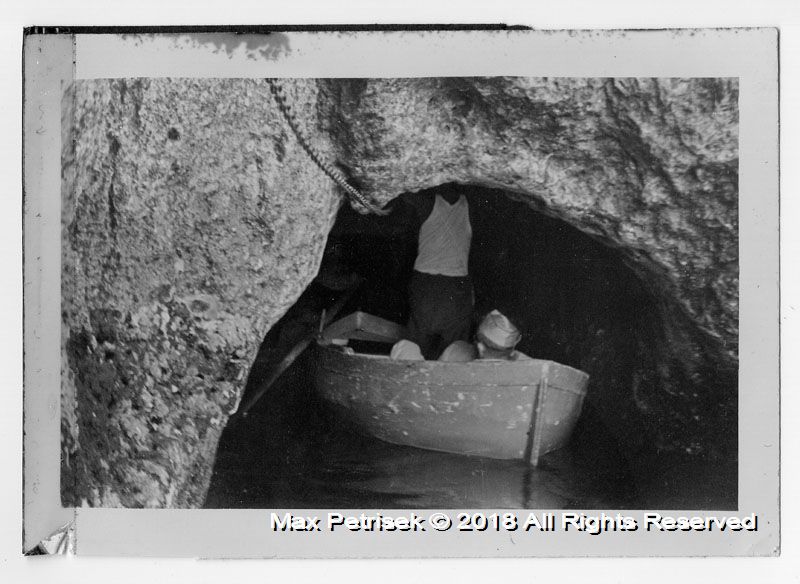

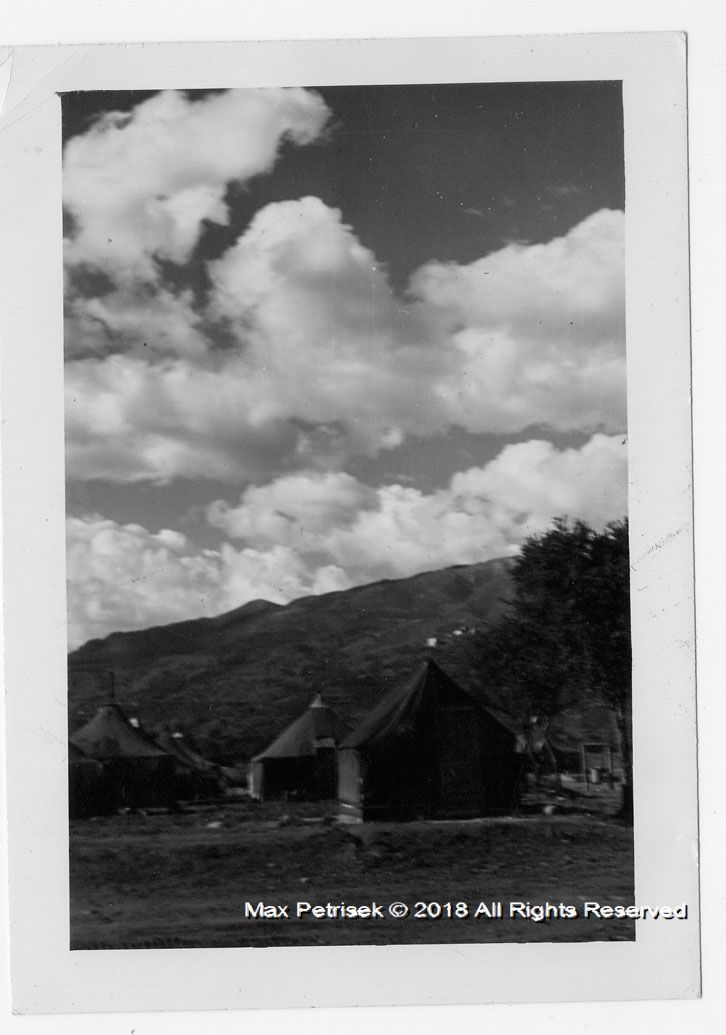

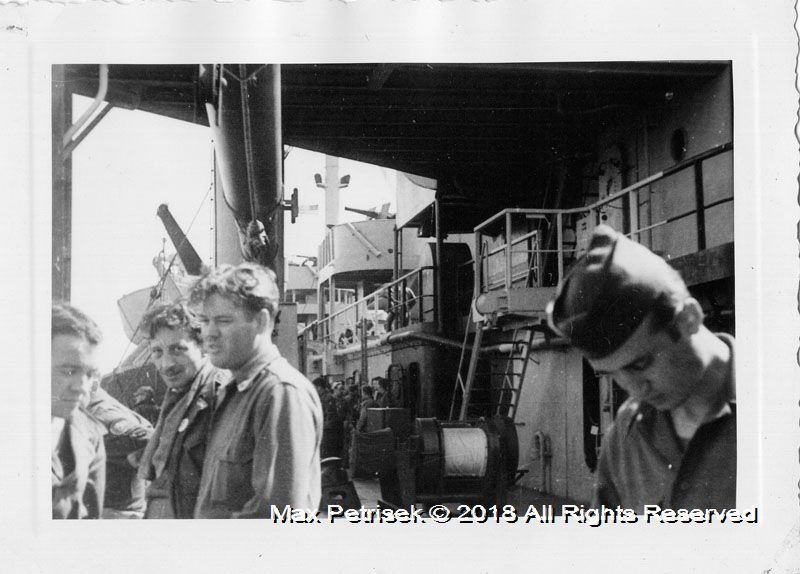

- The details are still vivid. The emergency field was the closest

(and) our only hope to get out of enemy territory (and) get help for our

dying tail gunner. It was tough to go 180 degree from home base. We had

difficulty getting the rest of our flight to leave us and "GO HOME". Our

radio was also OUT.

-

-

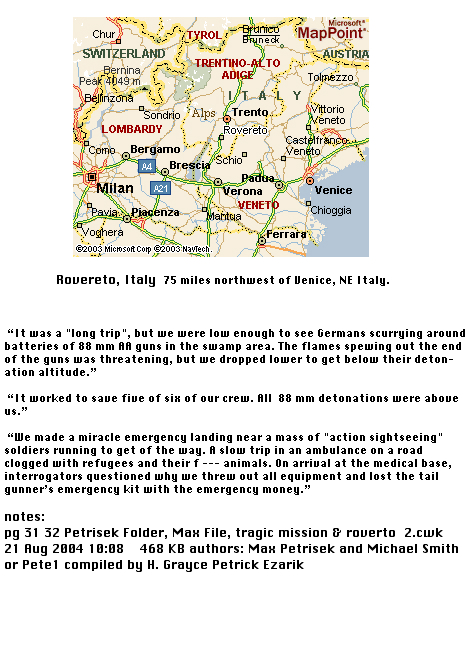

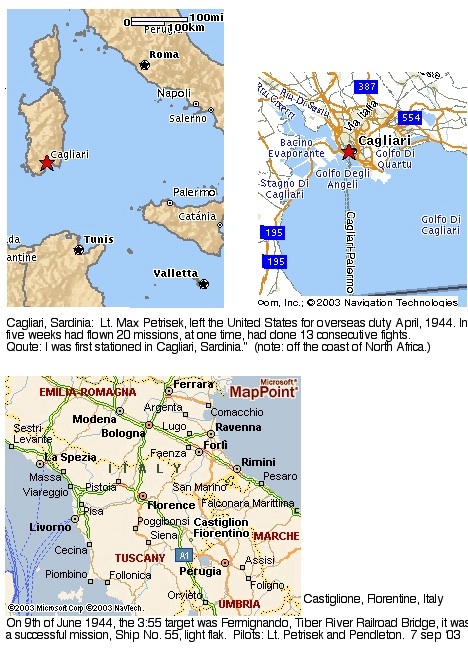

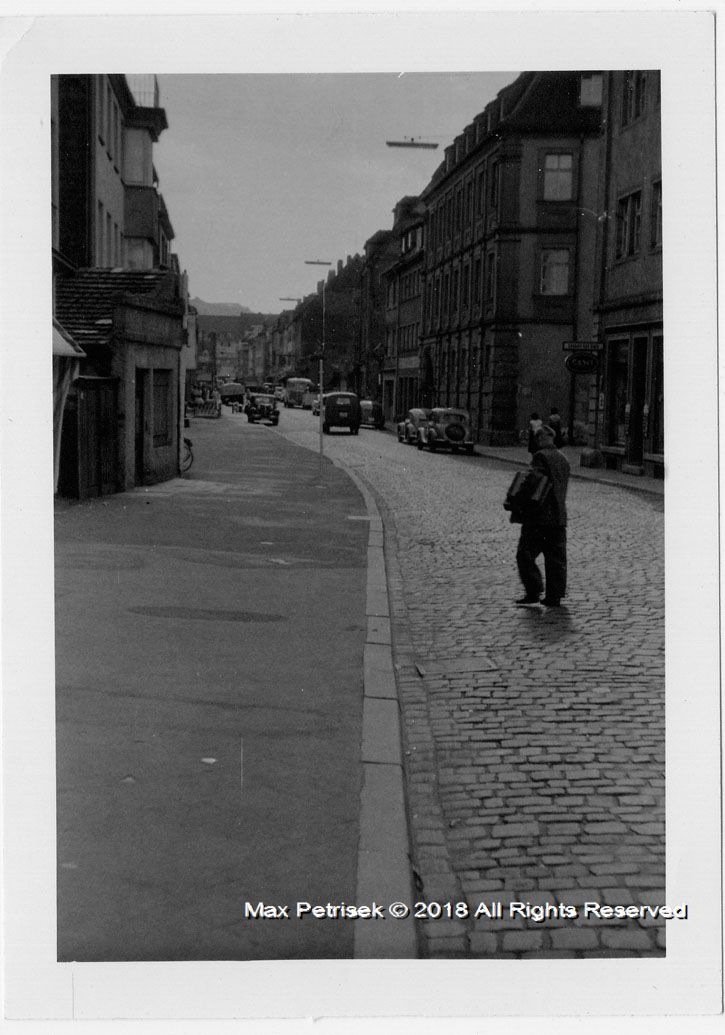

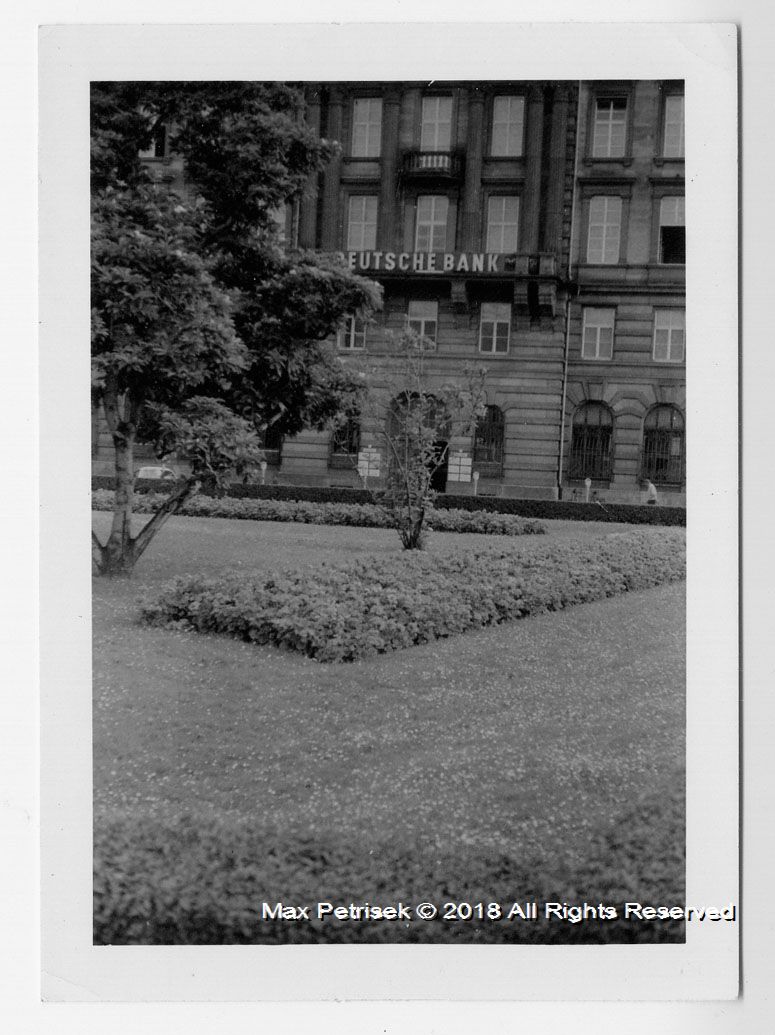

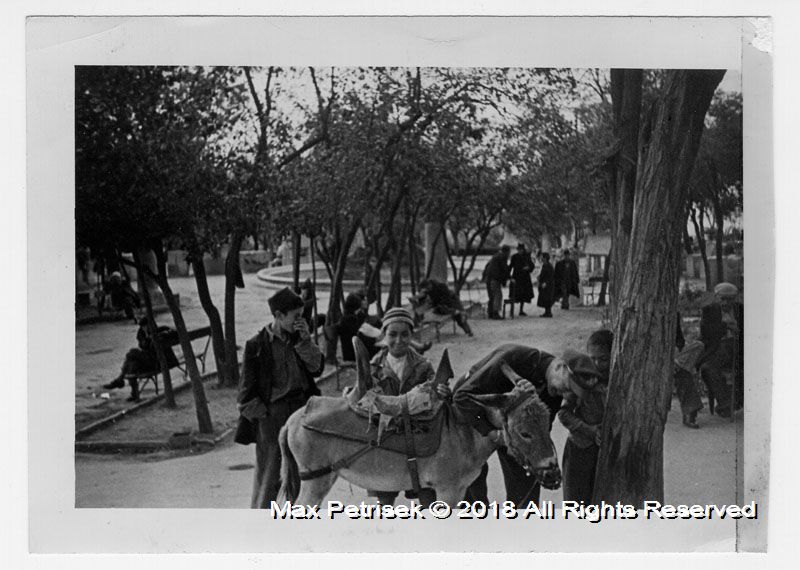

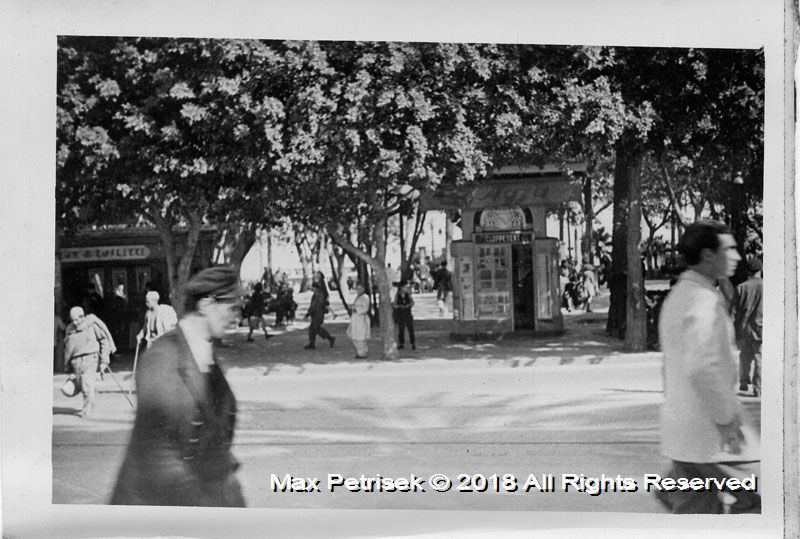

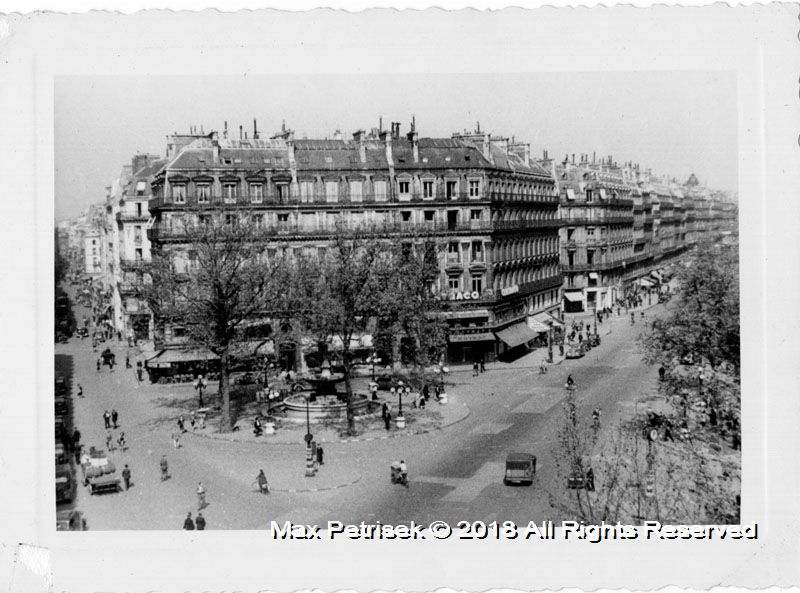

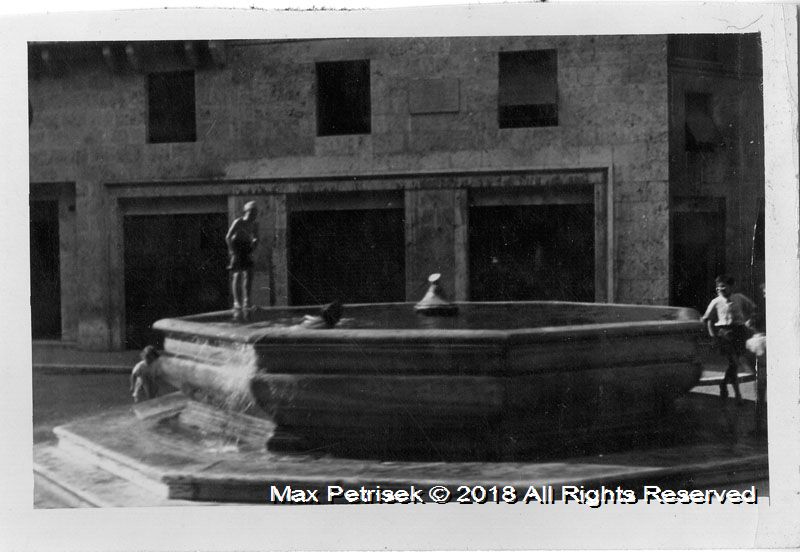

- Rovereto, Italy 75 miles northwest of Venice, Italy.

-

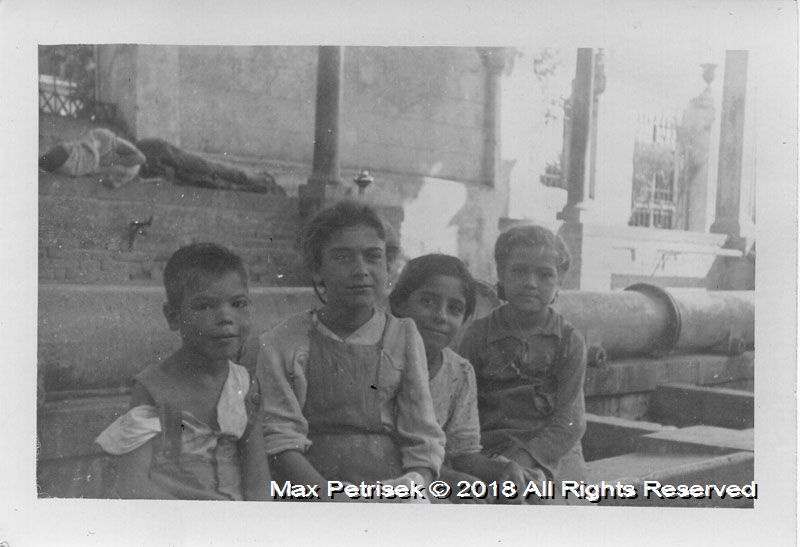

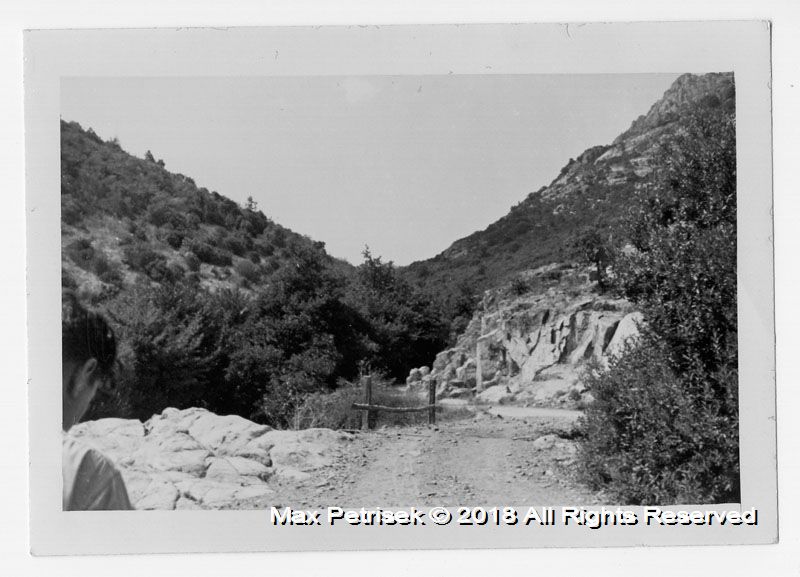

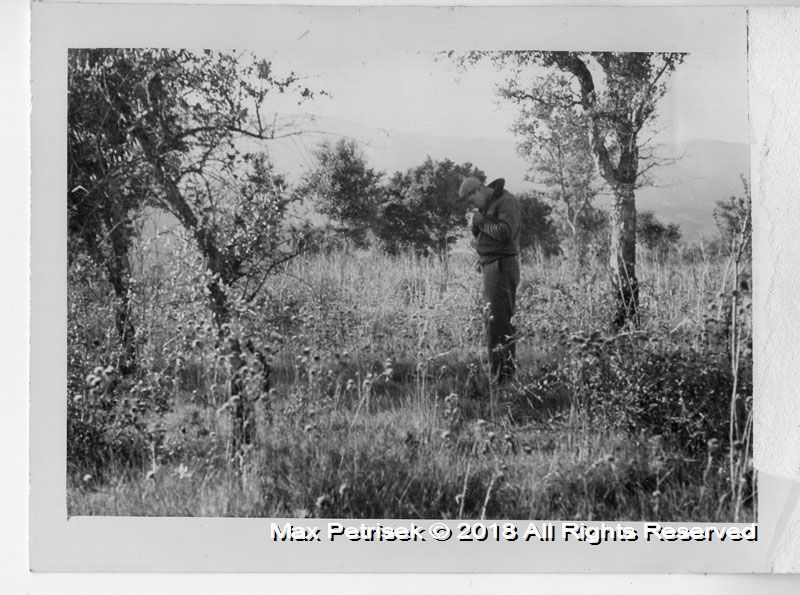

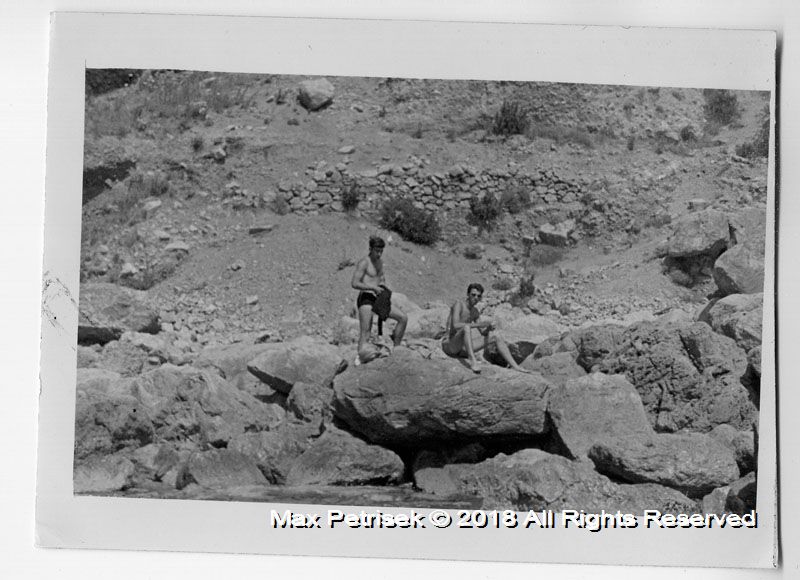

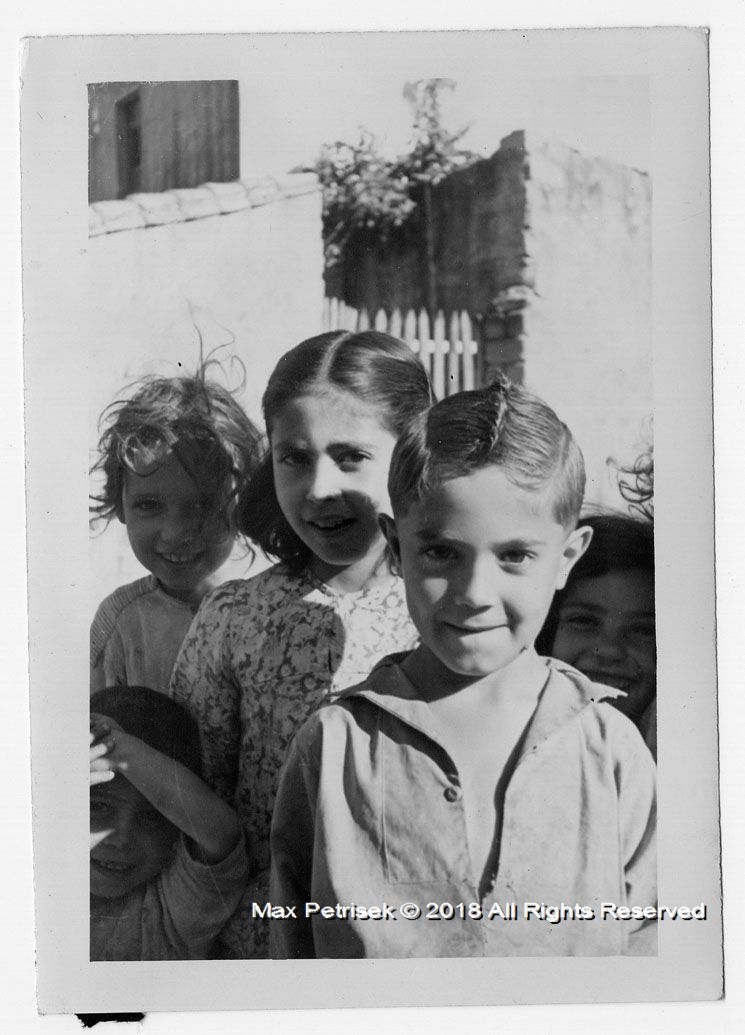

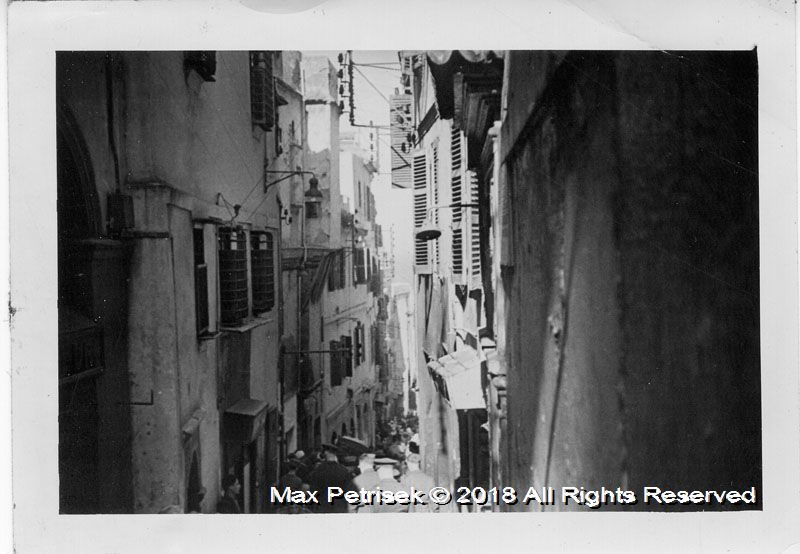

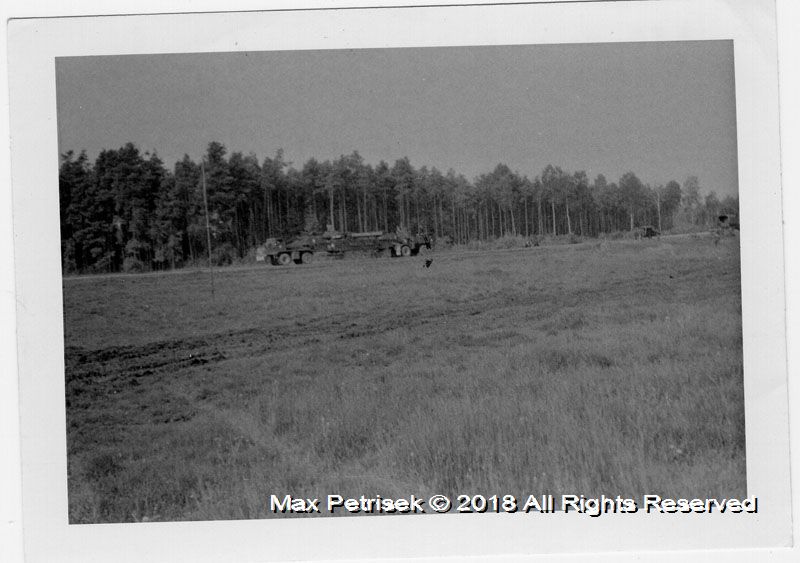

- It was a "long trip", but we were low enough to see Germans

scurrying around batteries of 88 mm AA guns in the swamp area. The

flames spewing out the end of the guns was threatening, but we dropped

lower to get below their detonation altitude.

-

- It worked to save five of six of our crew. All 88 mm detonations

were above us.

-

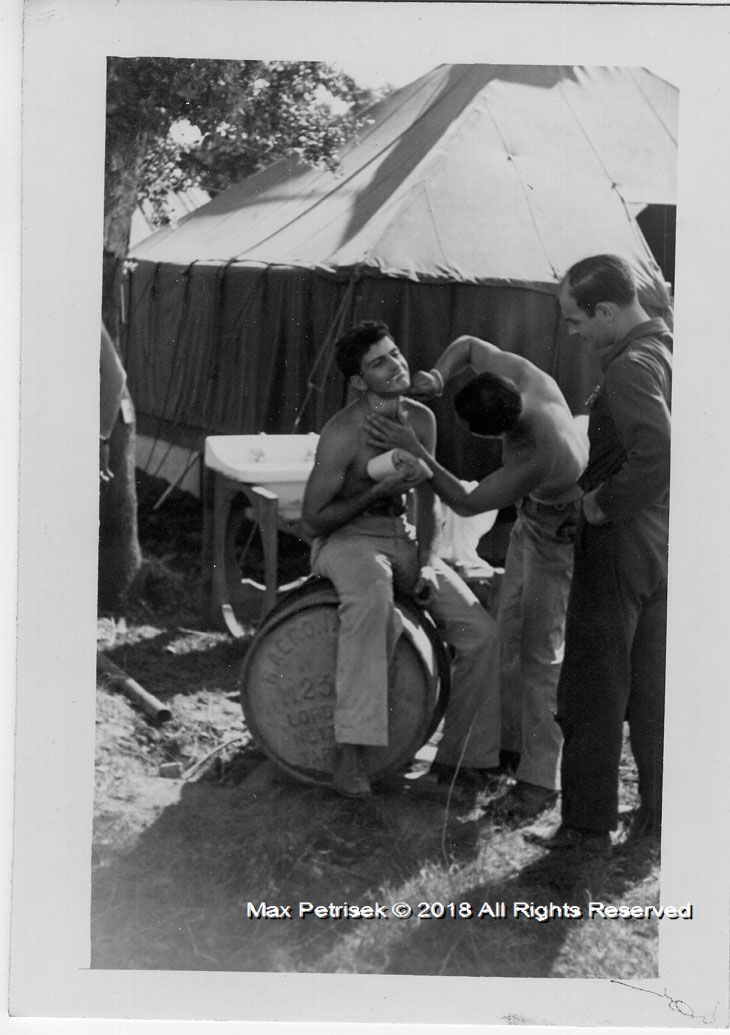

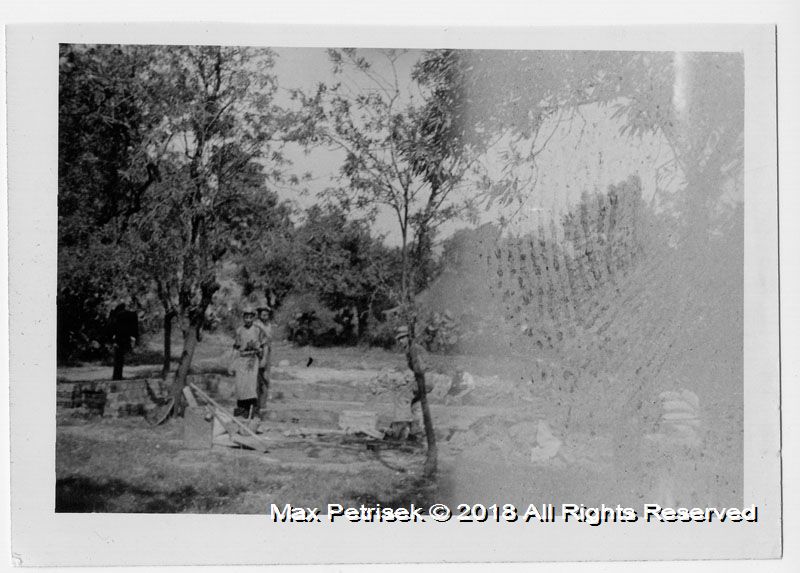

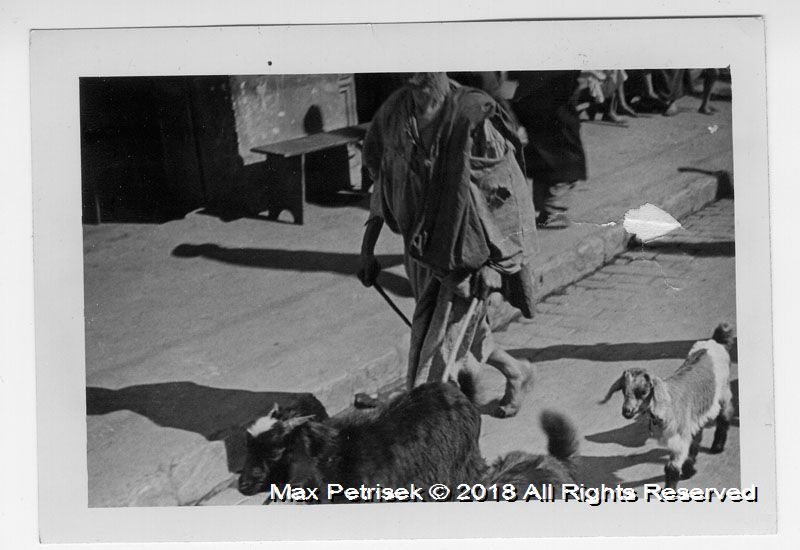

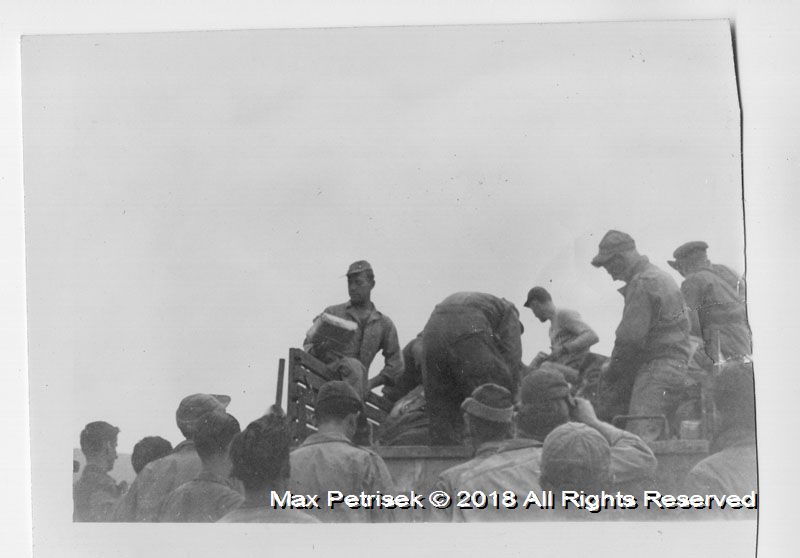

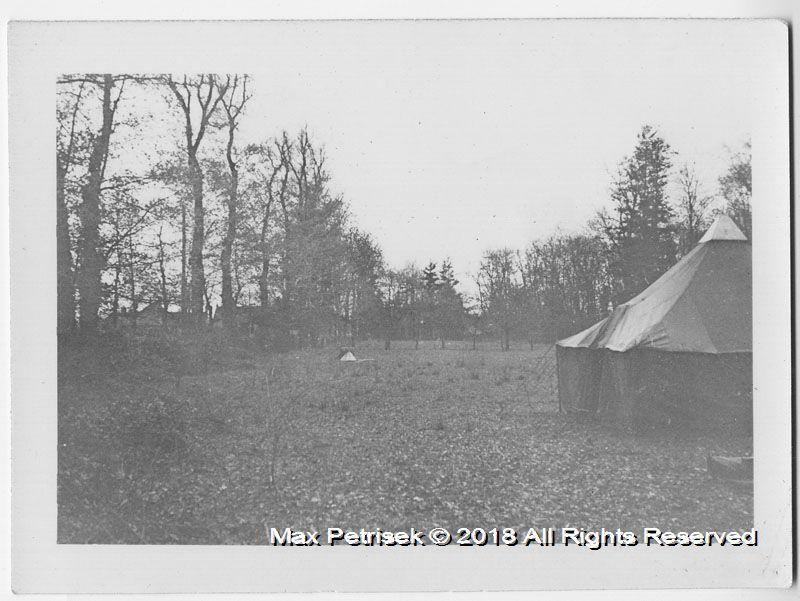

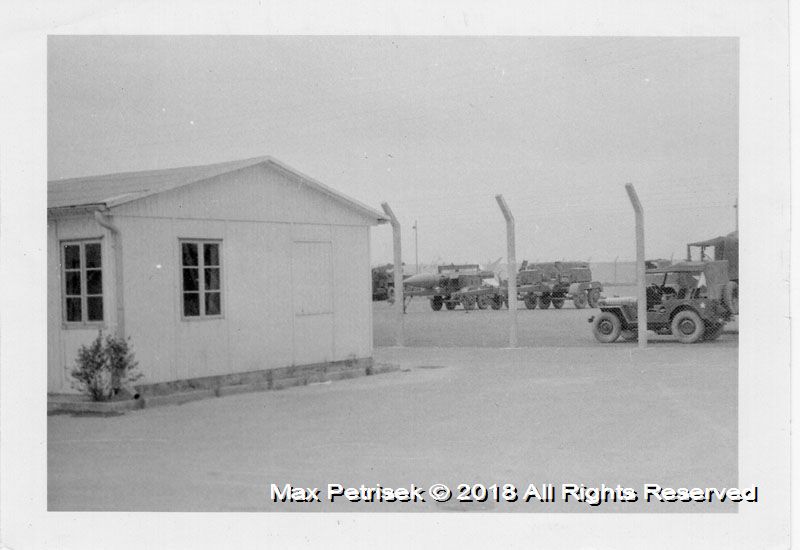

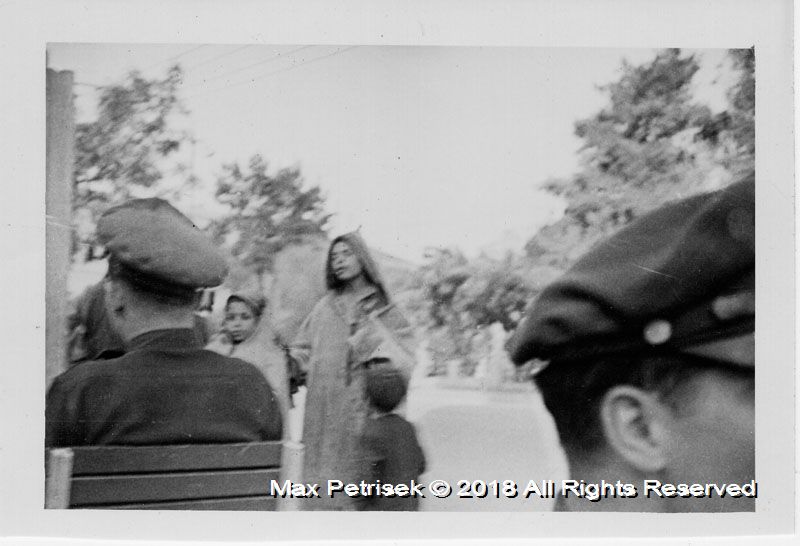

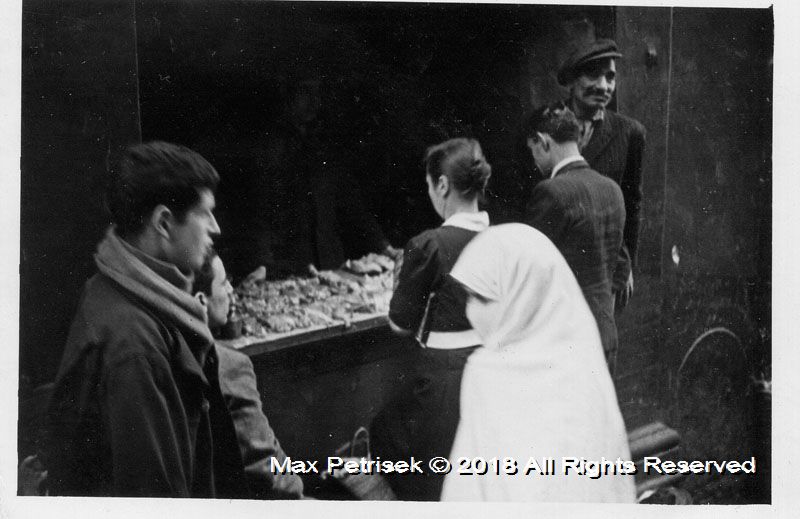

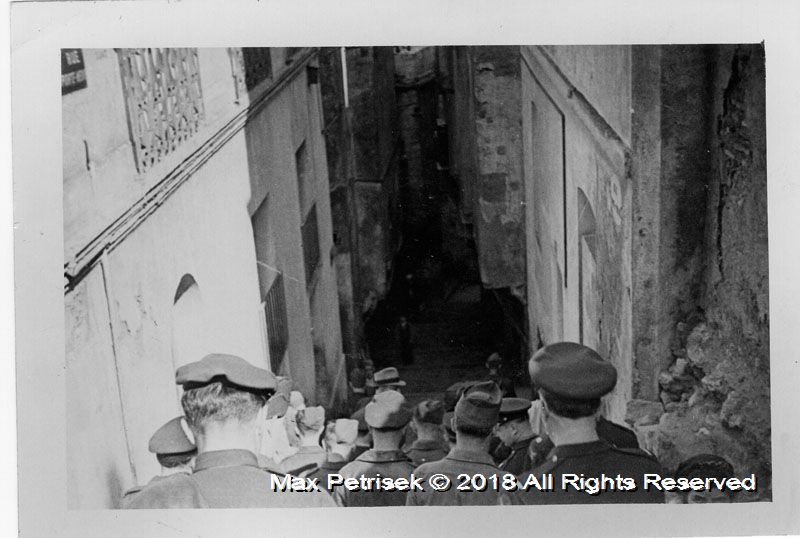

- We made a miracle emergency landing near a mass of "action

sightseeing" soldiers running to get of the way. A slow trip in an

ambulance on a road clogged with refugees and their f --- animals. On

arrival at the medical base, interrogators questioned why we threw out

all equipment and lost the tail gunner's emergency kit with the

emergency money."

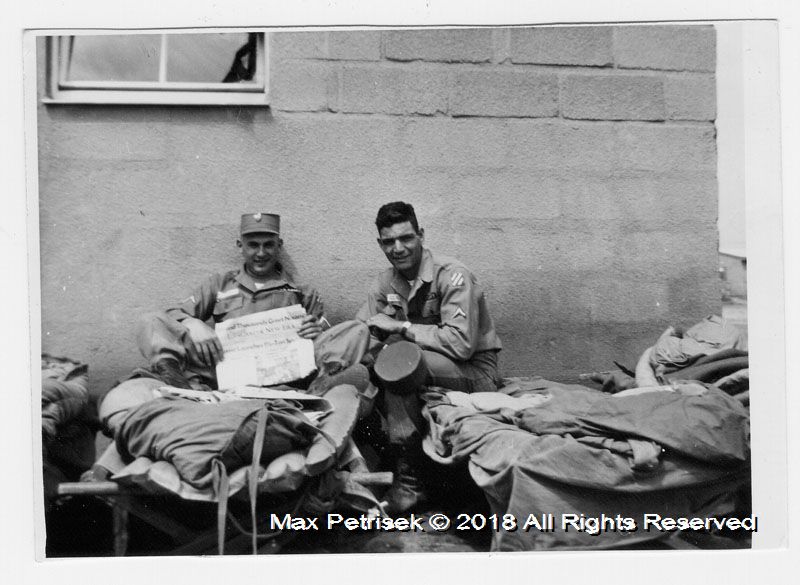

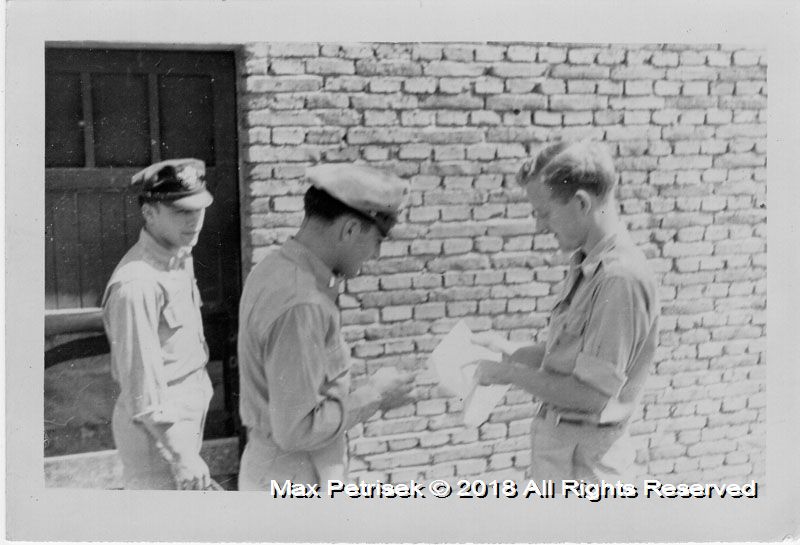

Related story from Bill Churchman,

provided by Max Petrisek.

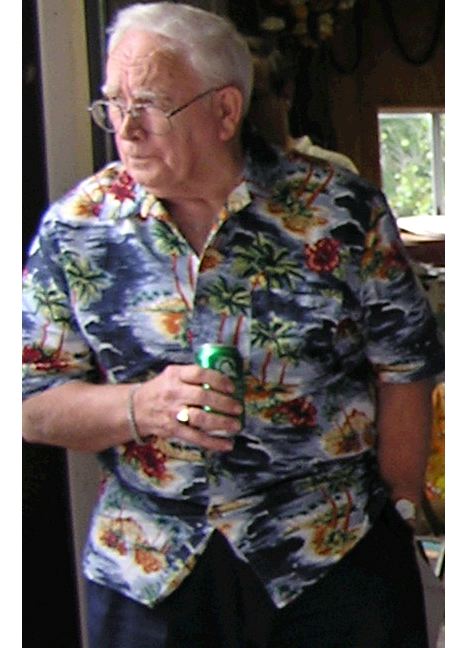

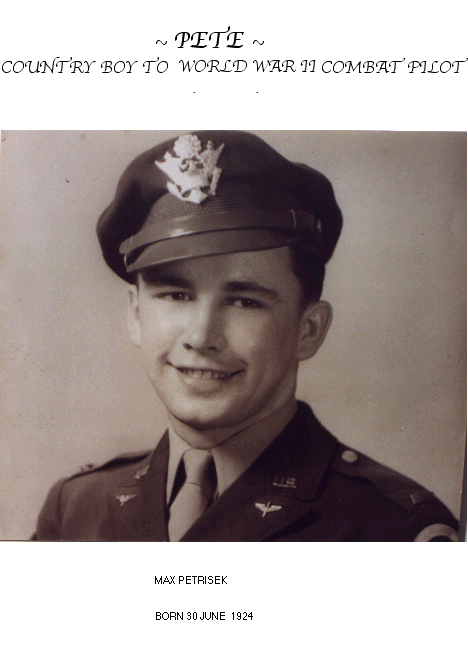

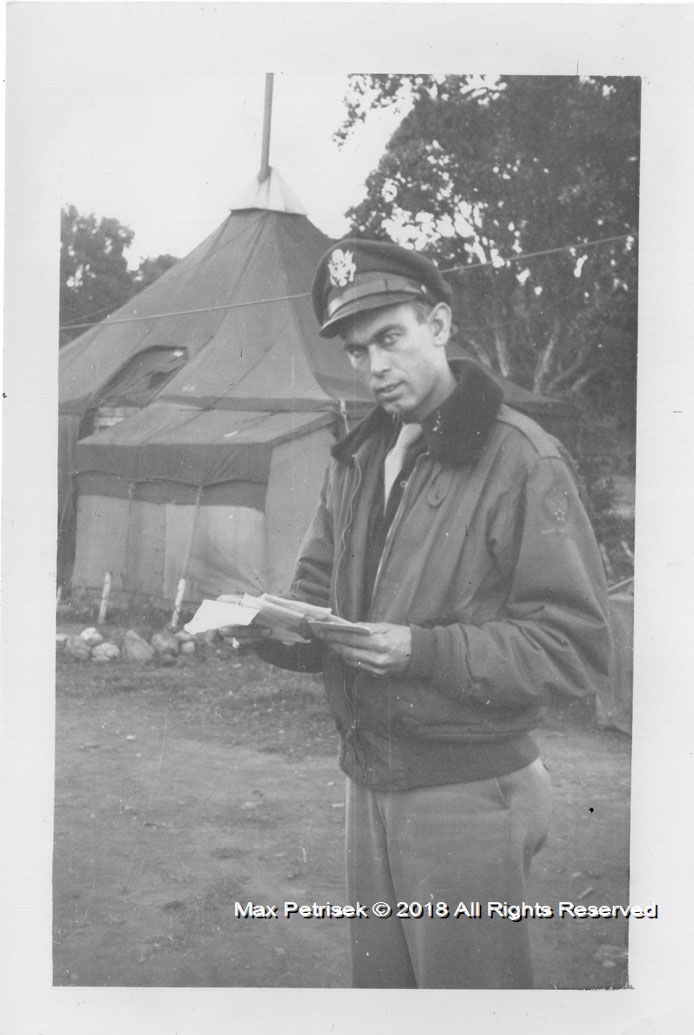

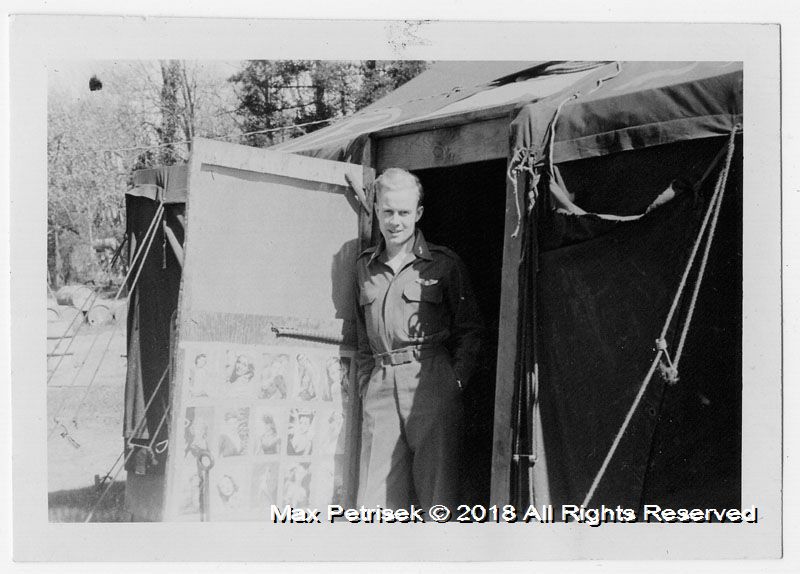

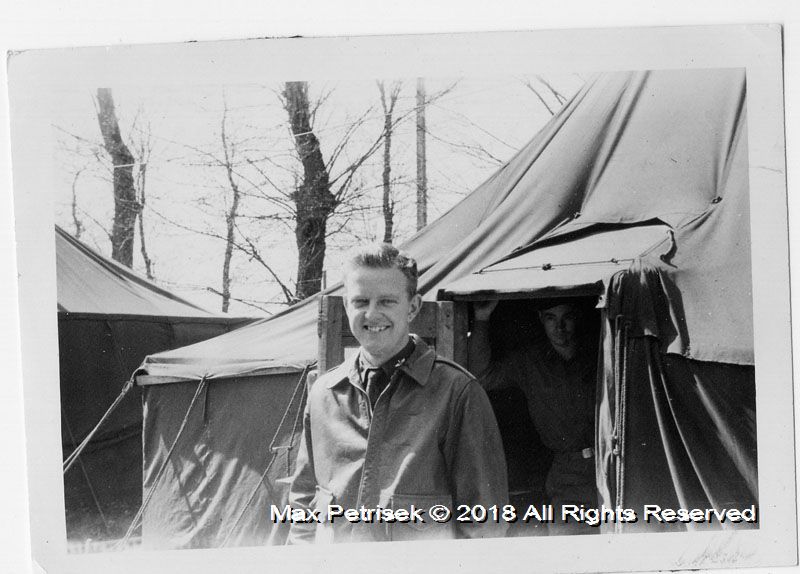

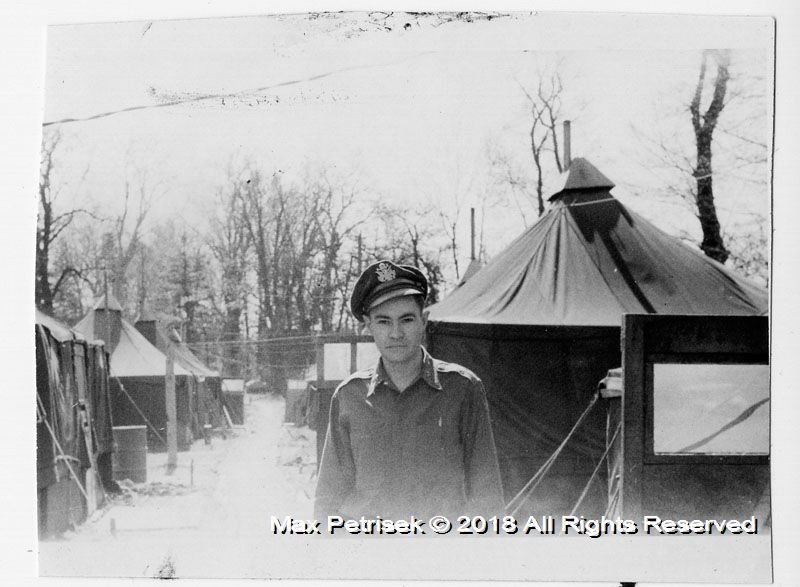

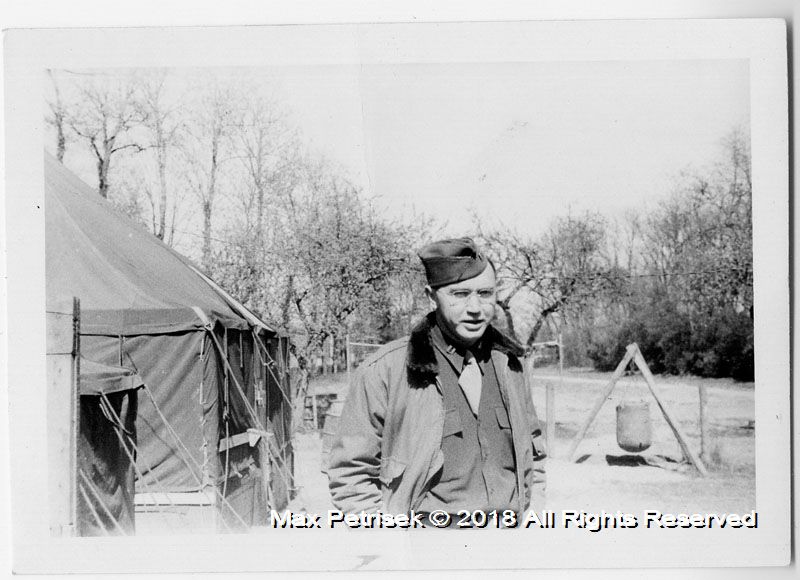

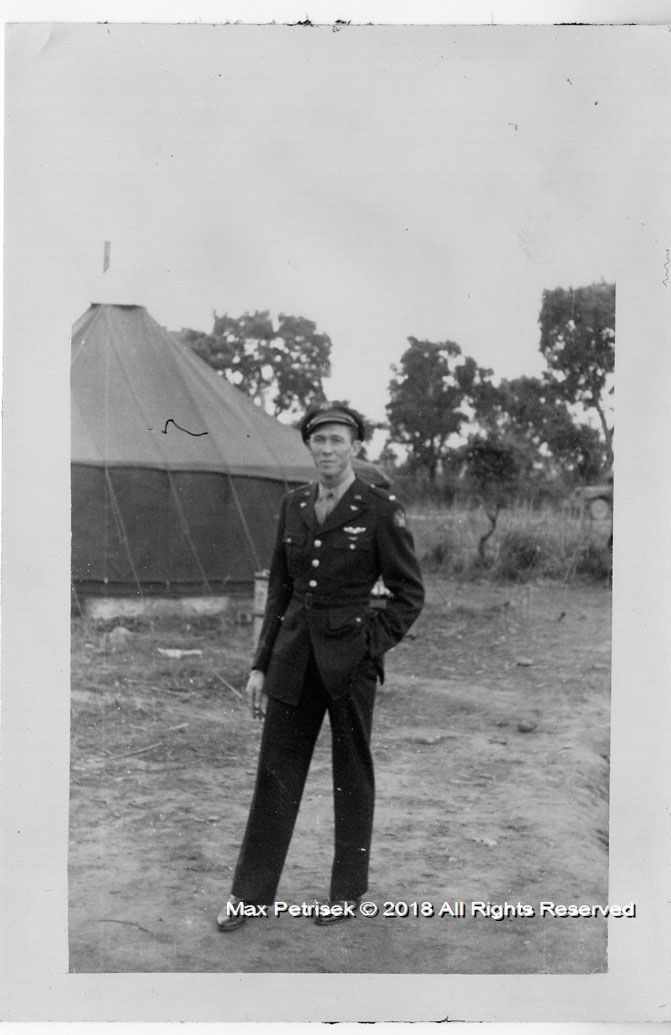

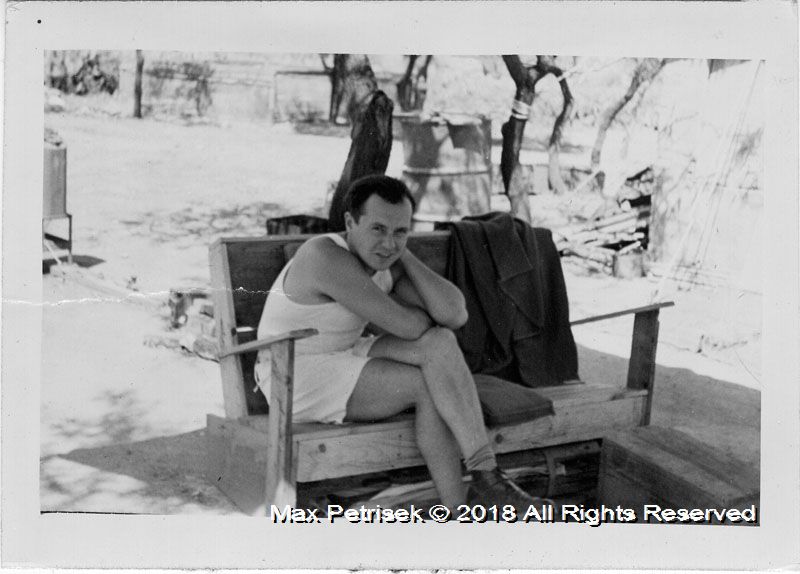

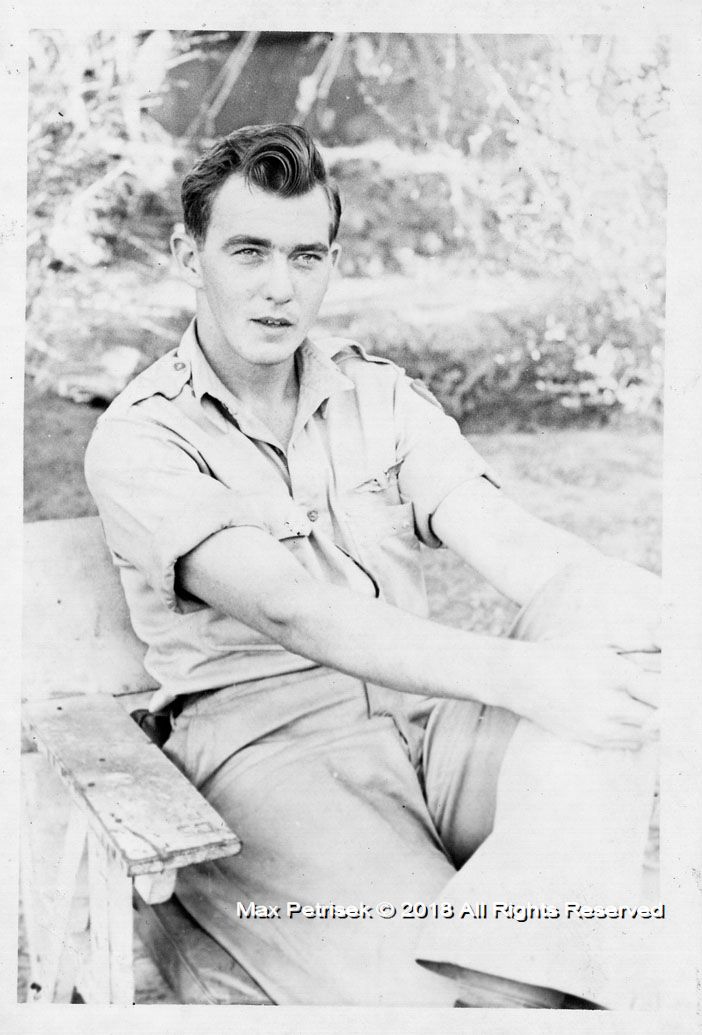

“Pete, Country-boy to Combat Pilot”

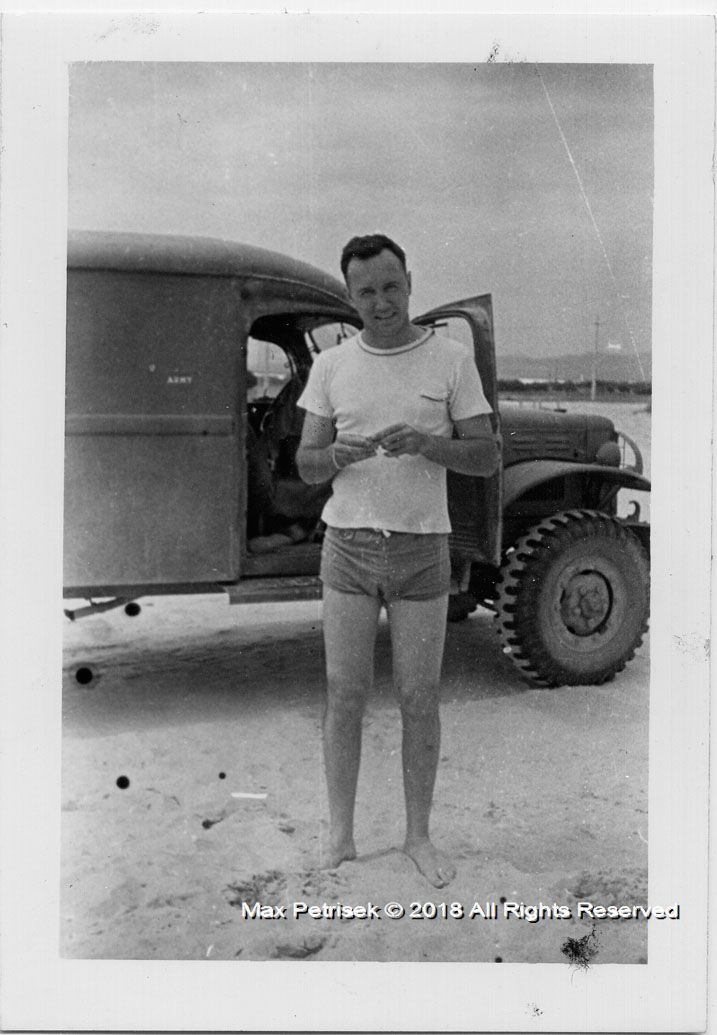

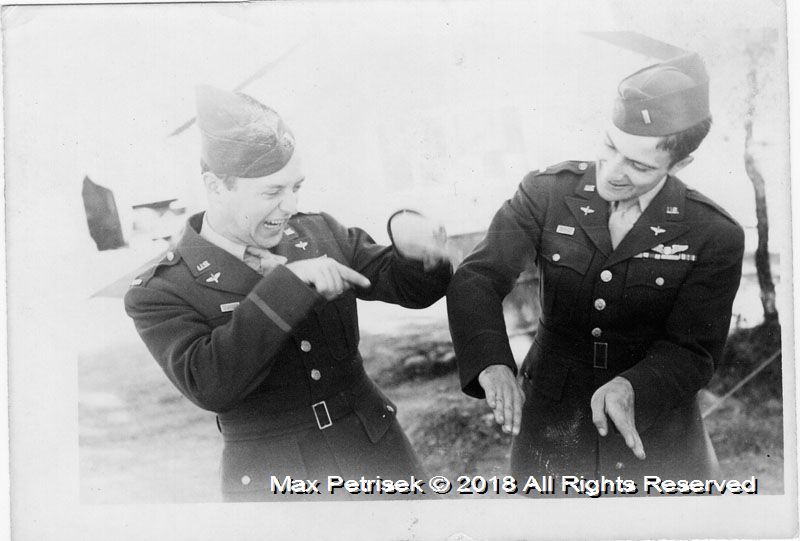

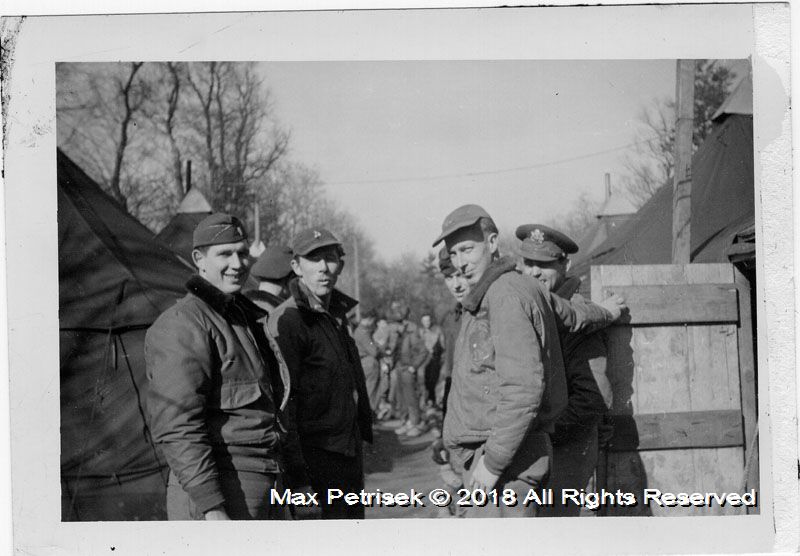

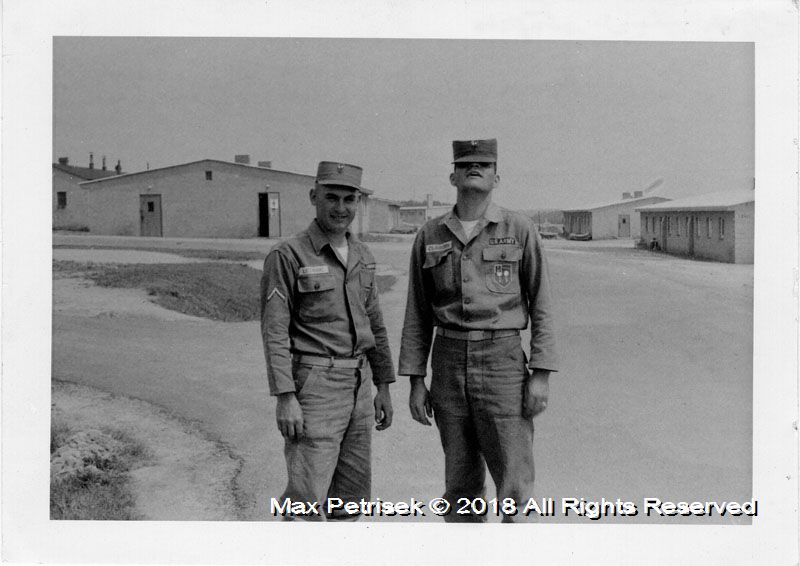

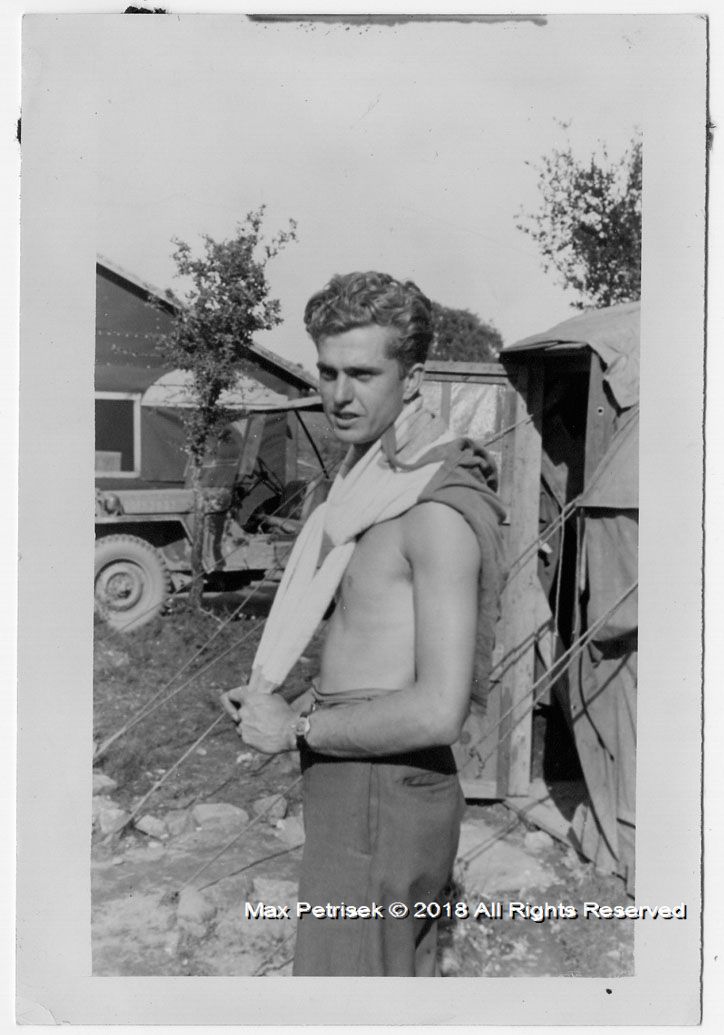

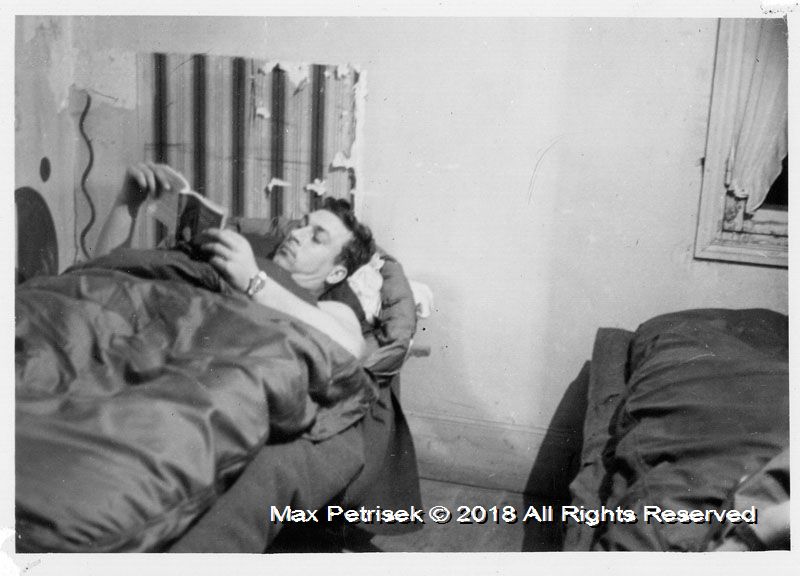

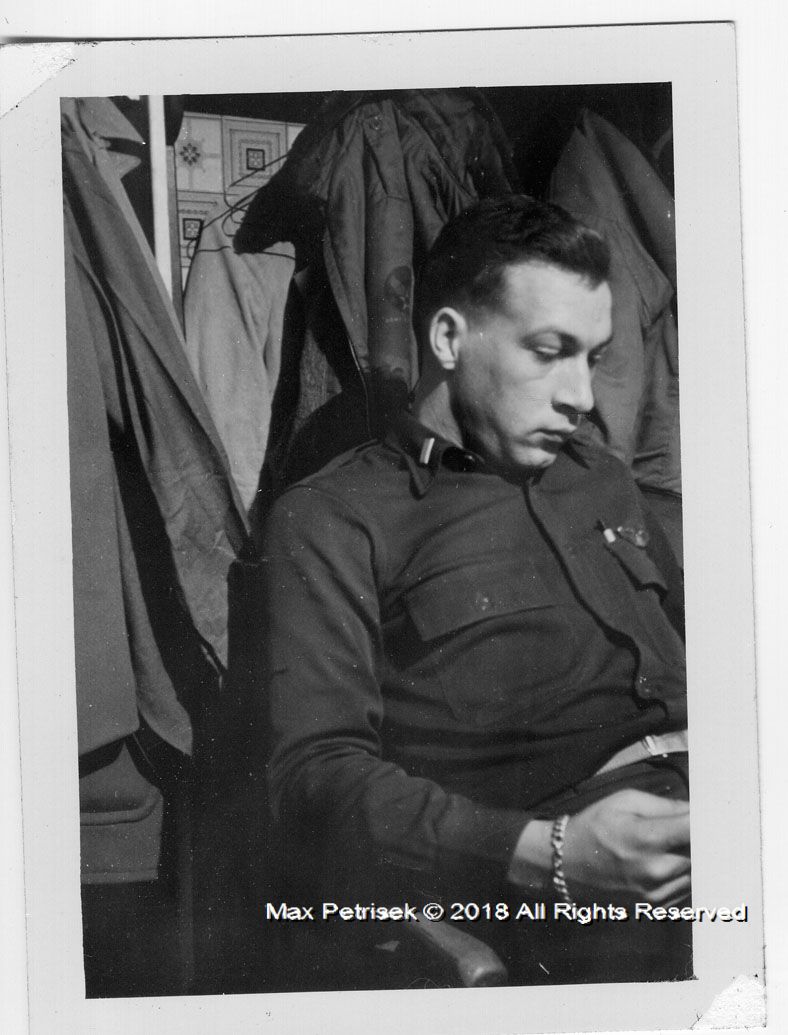

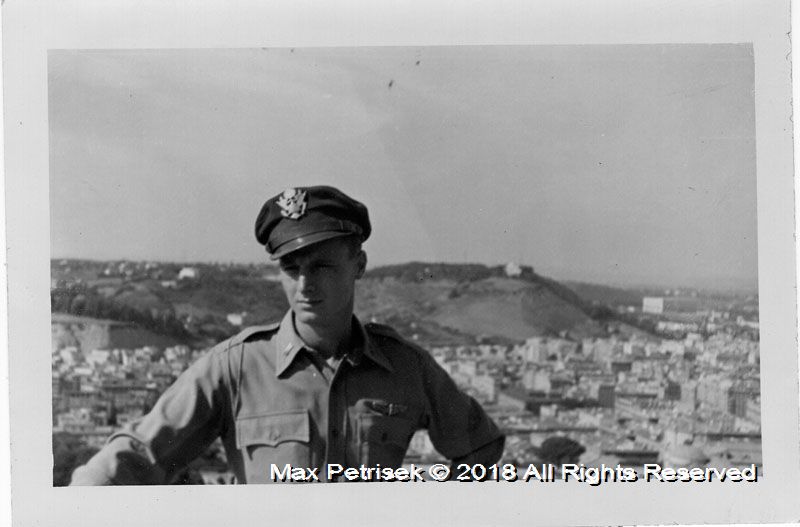

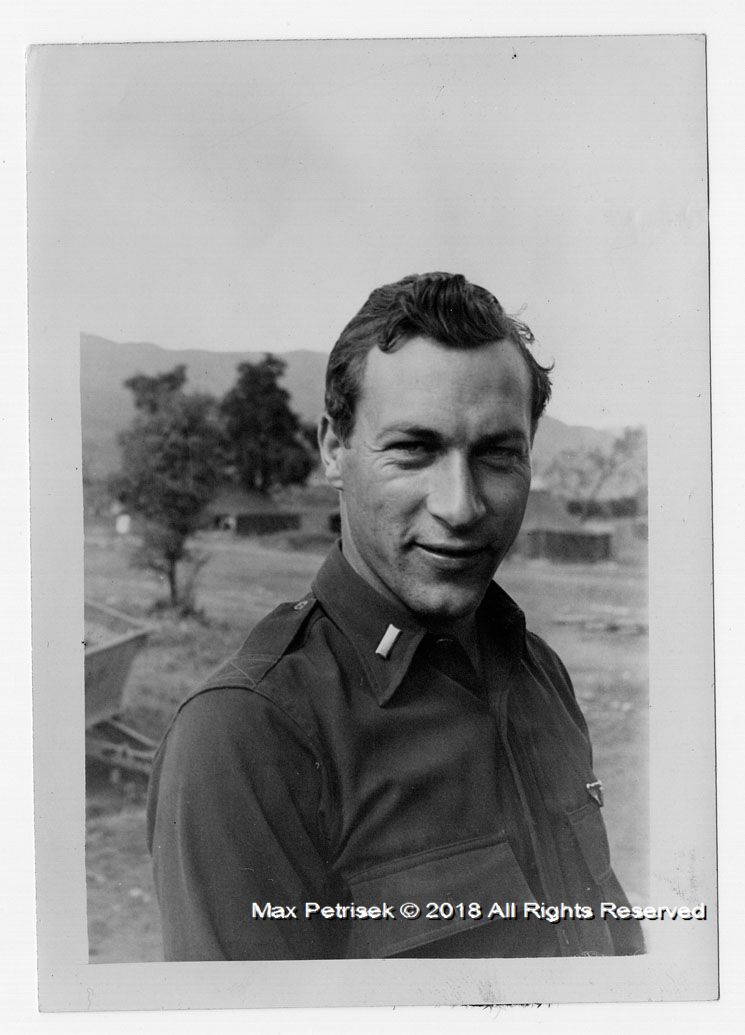

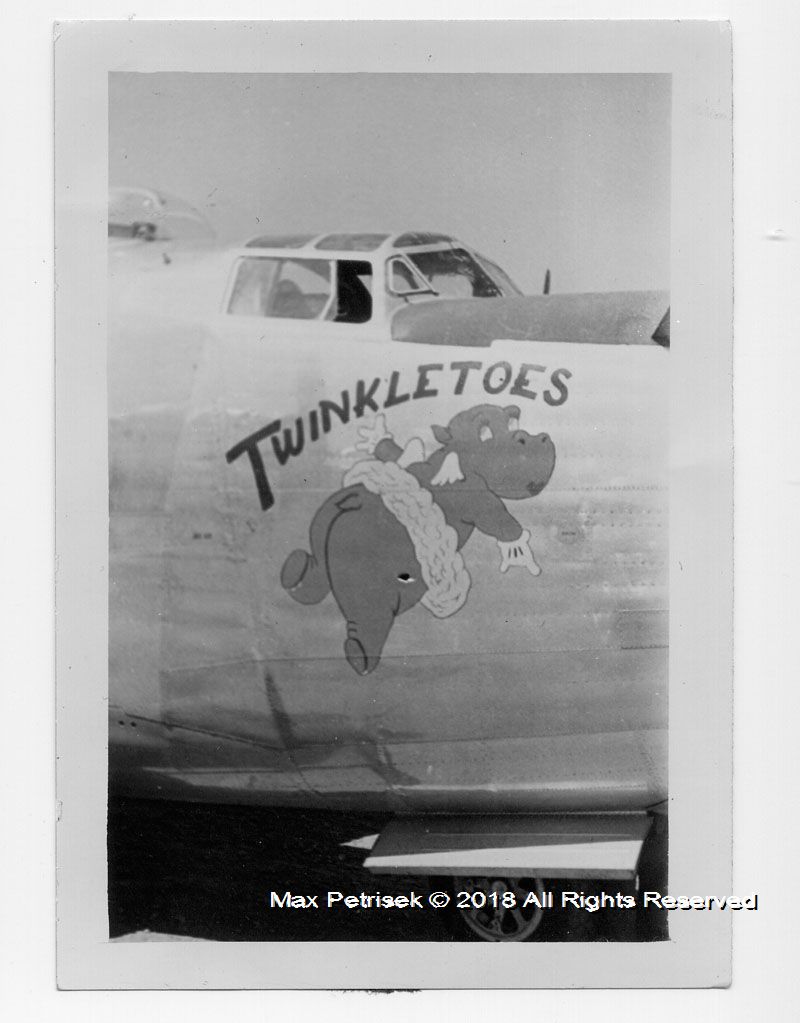

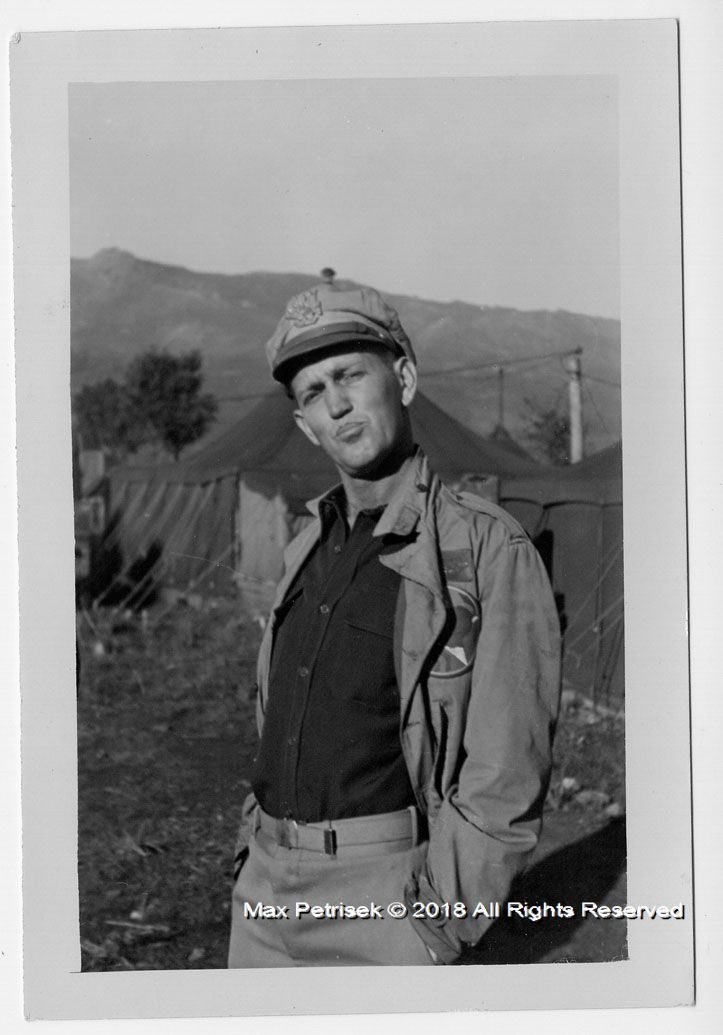

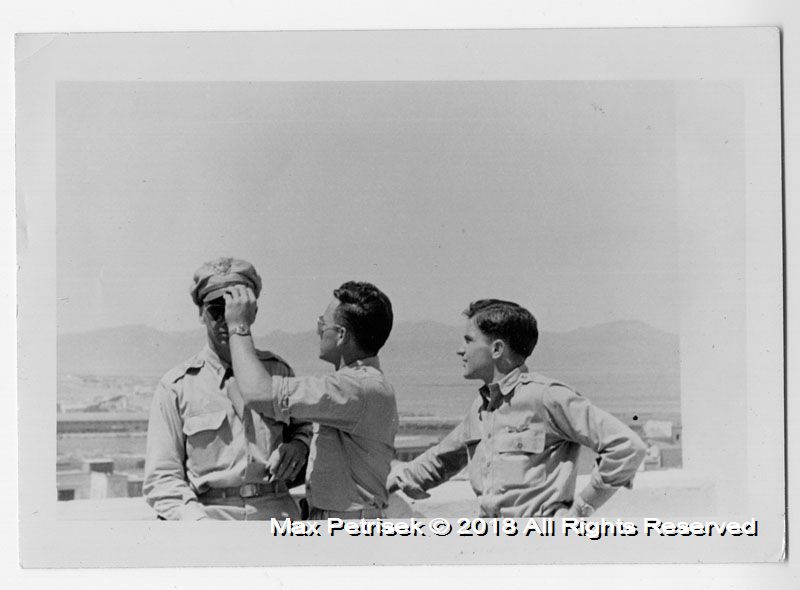

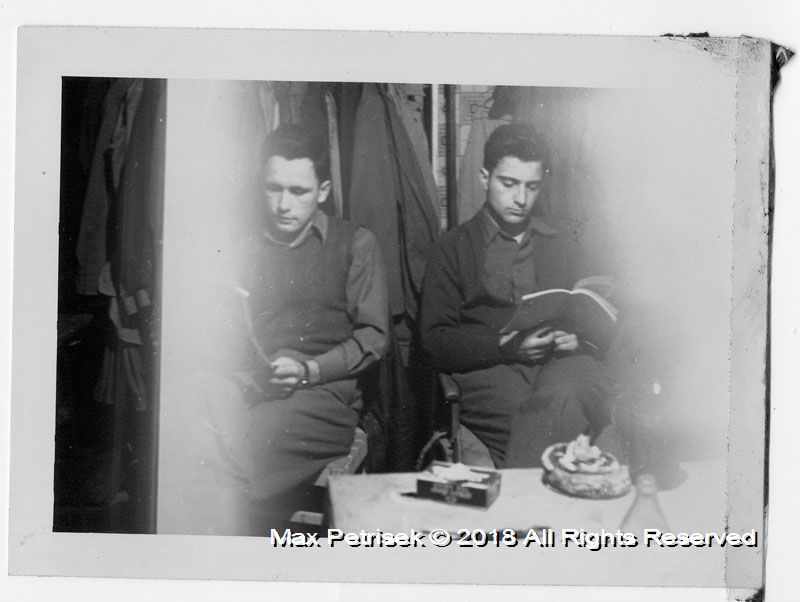

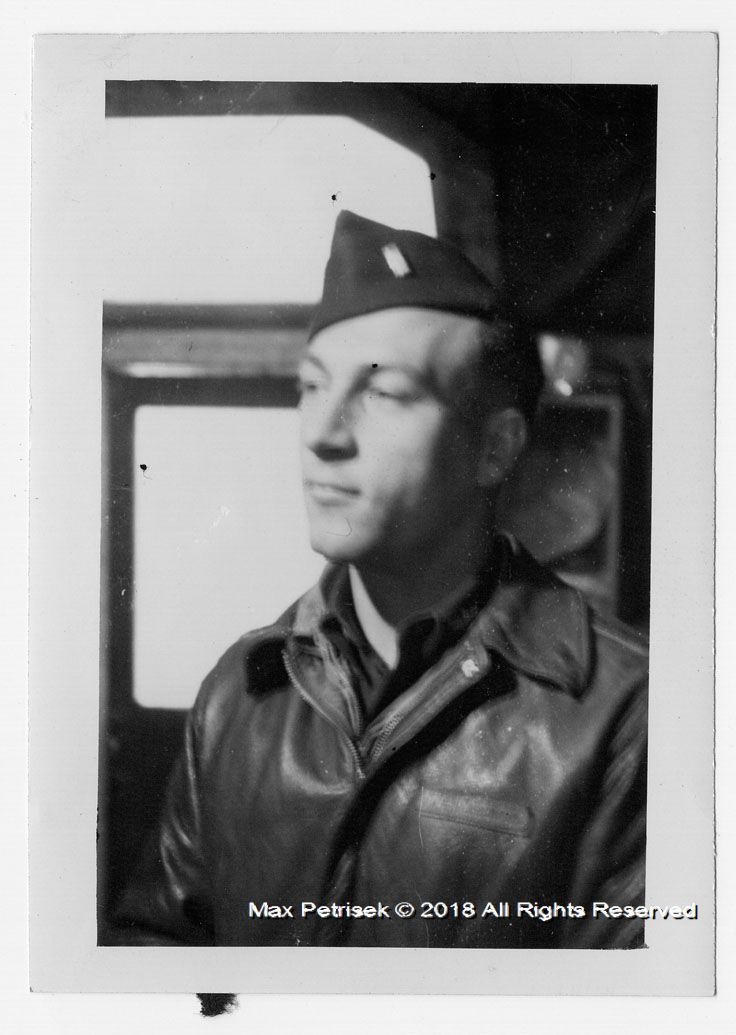

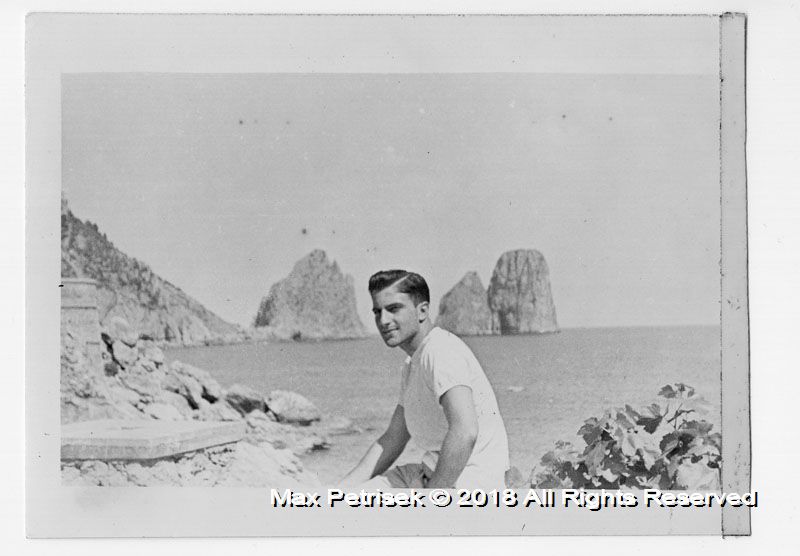

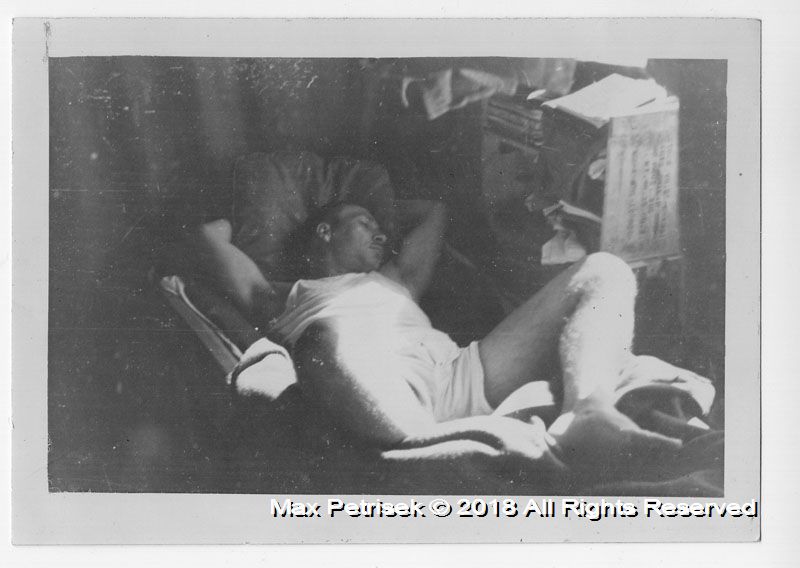

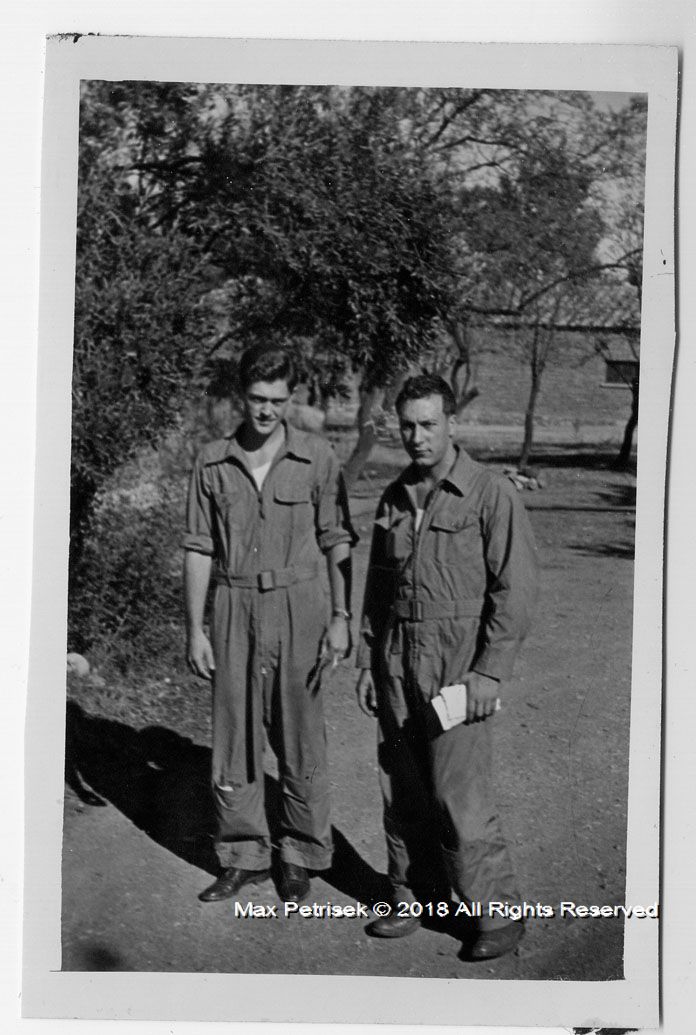

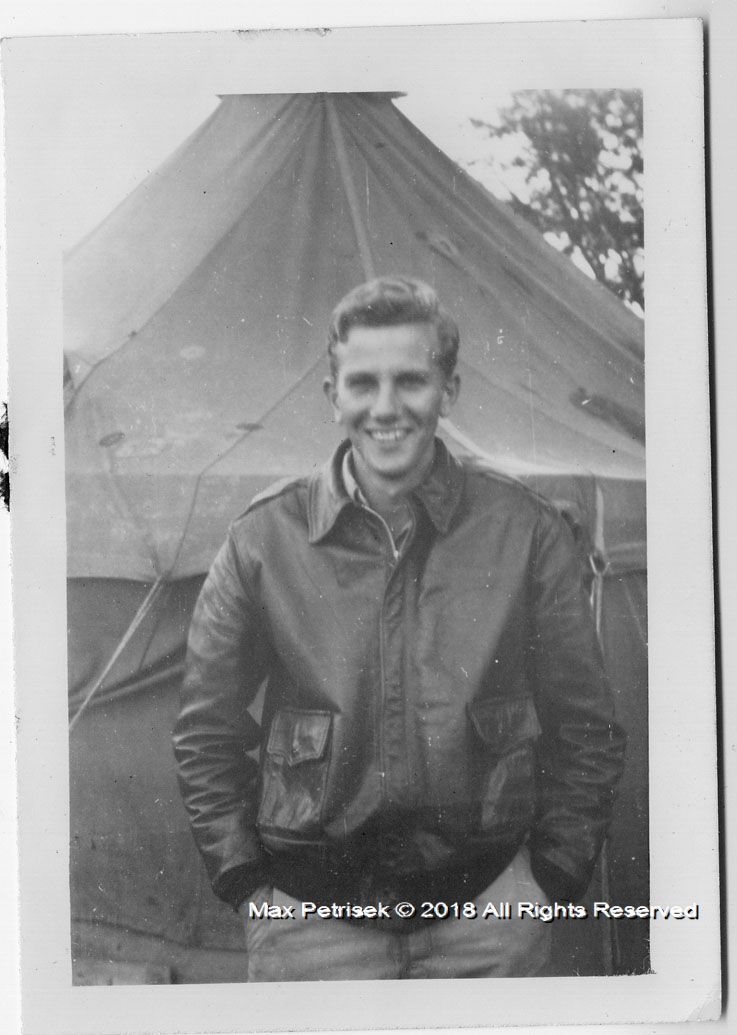

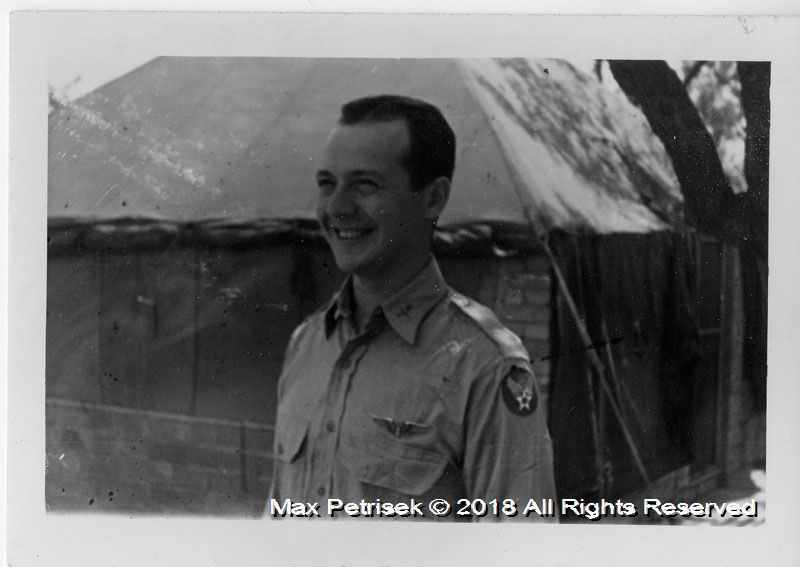

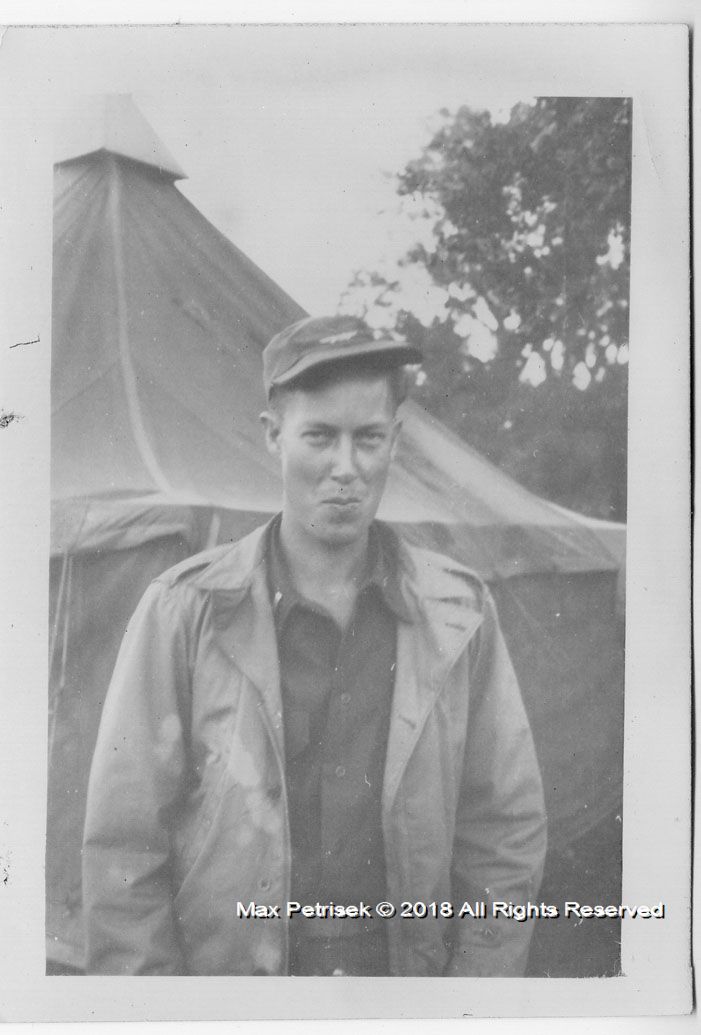

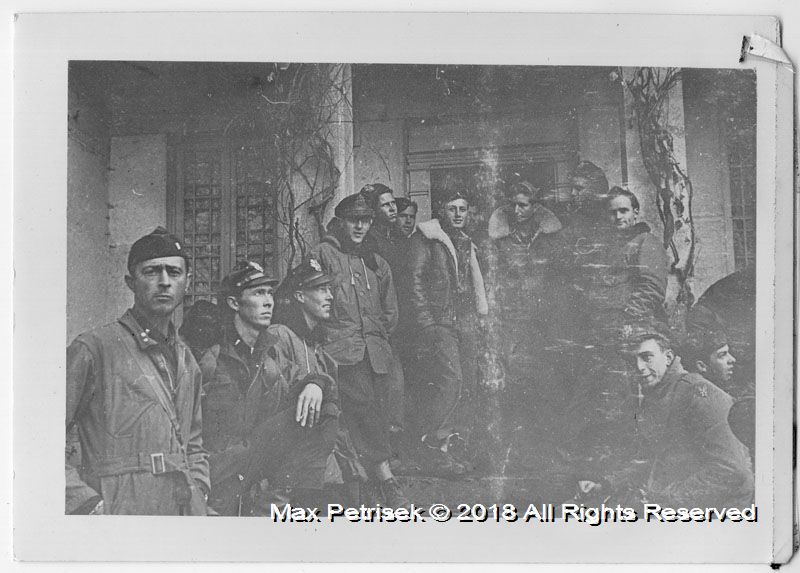

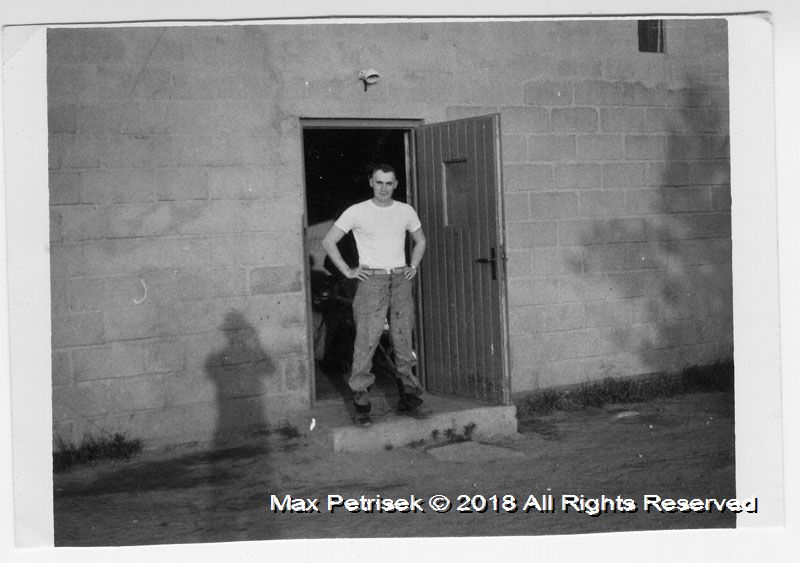

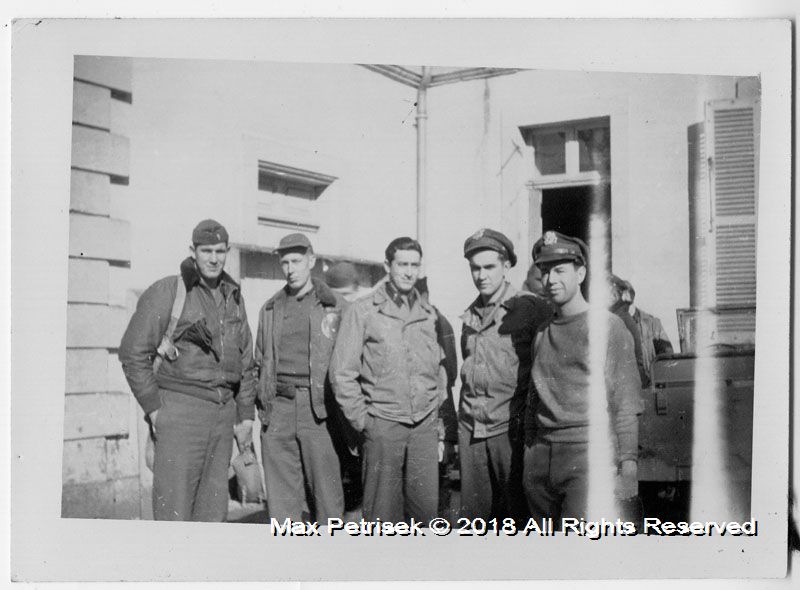

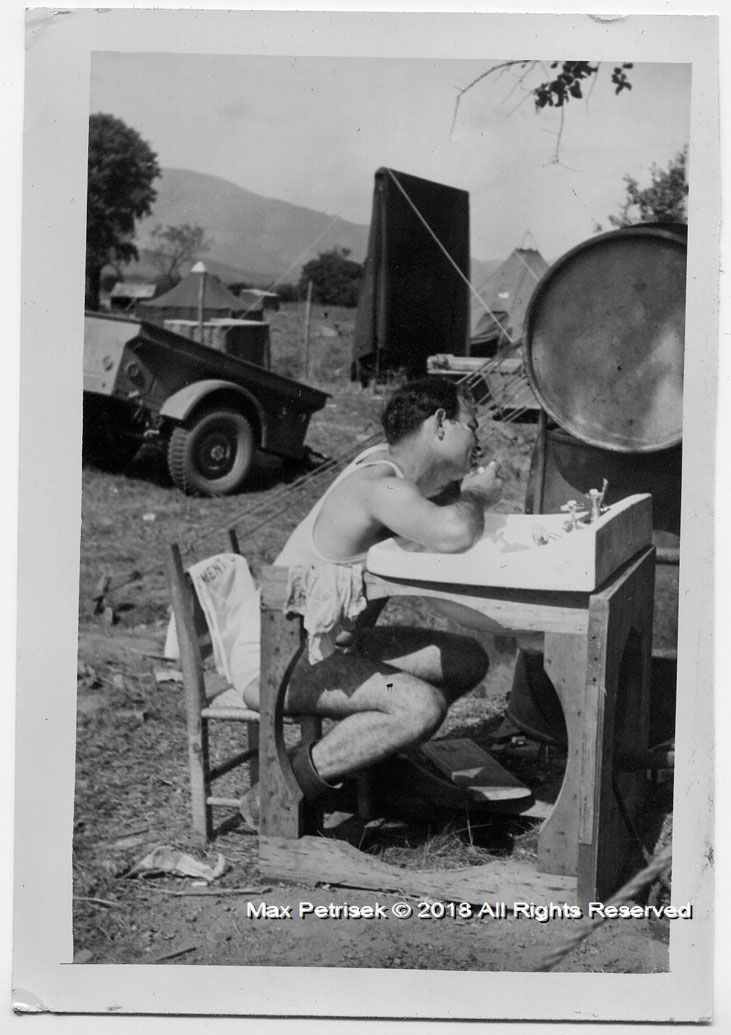

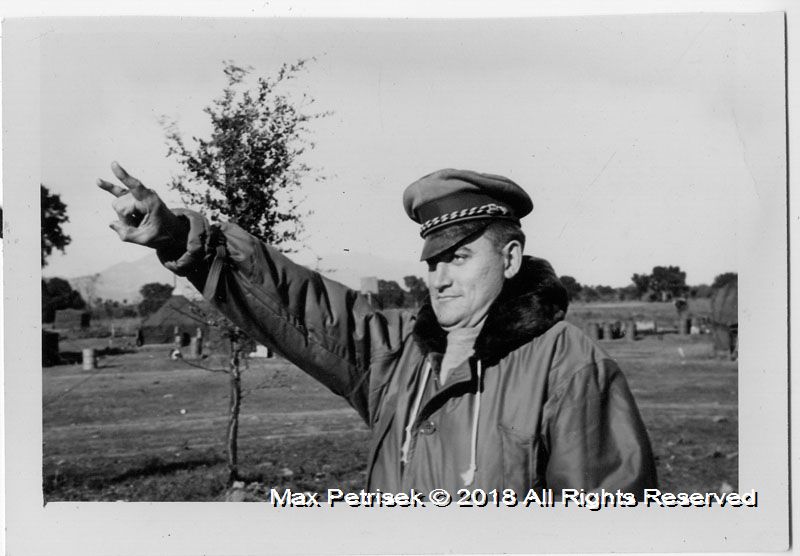

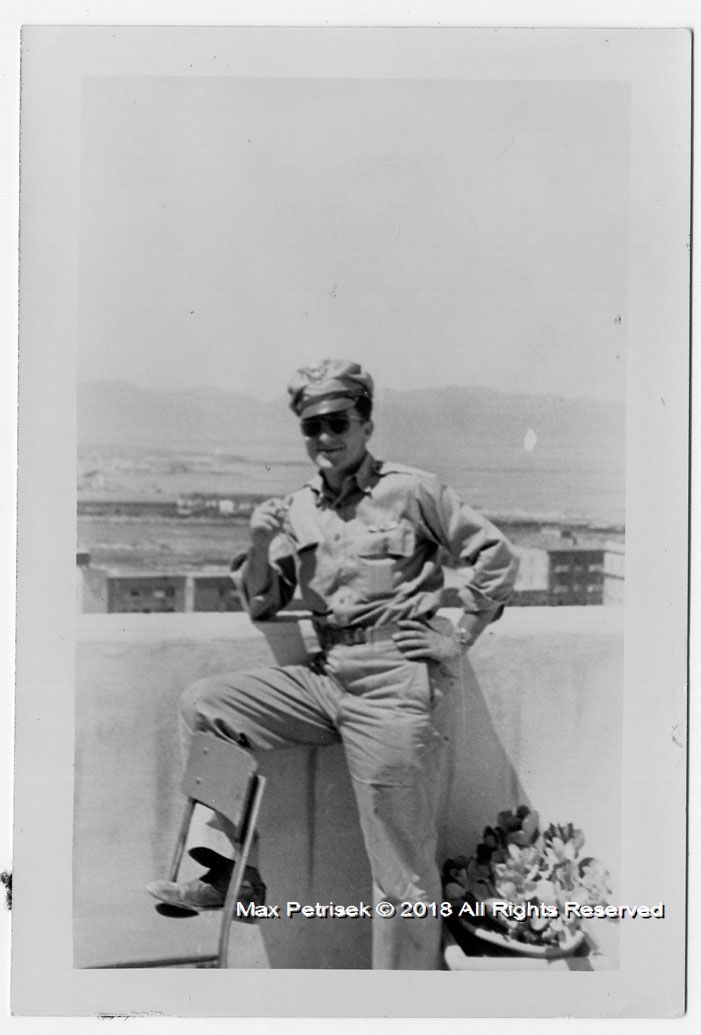

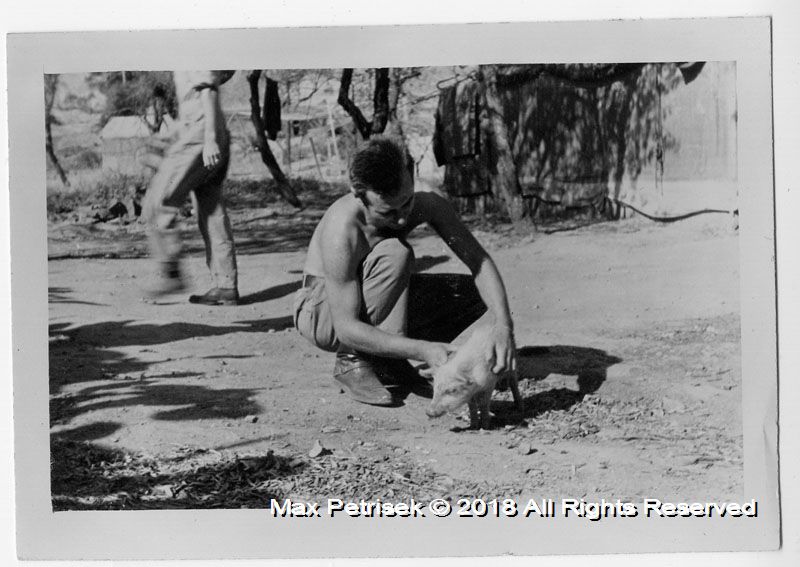

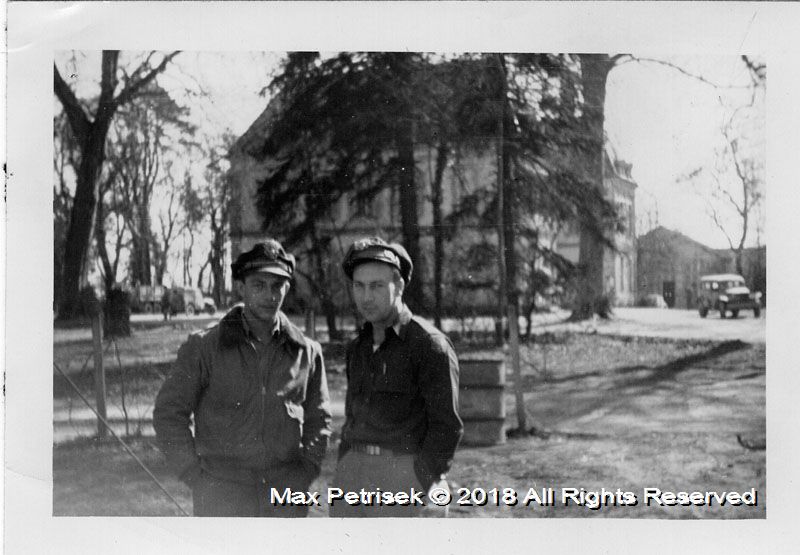

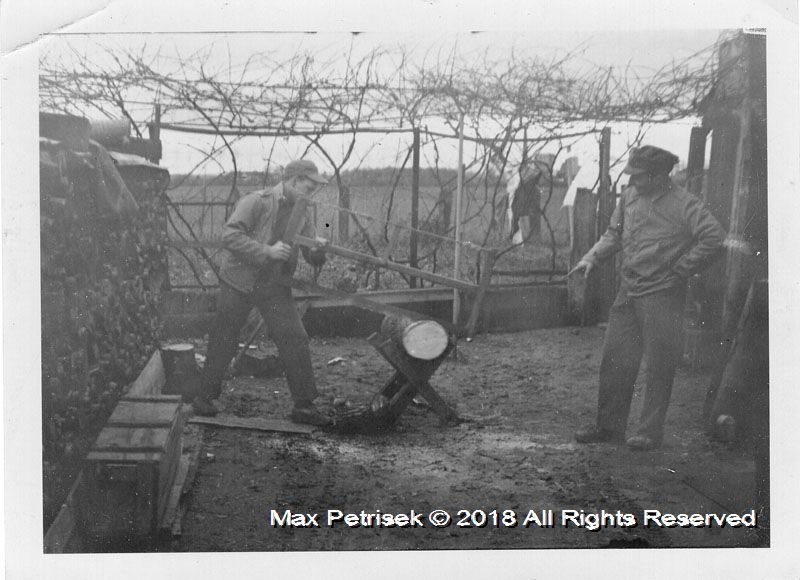

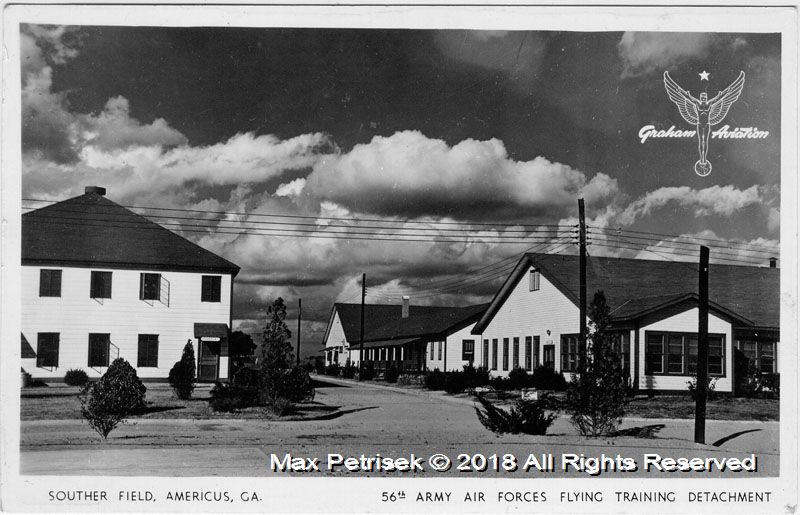

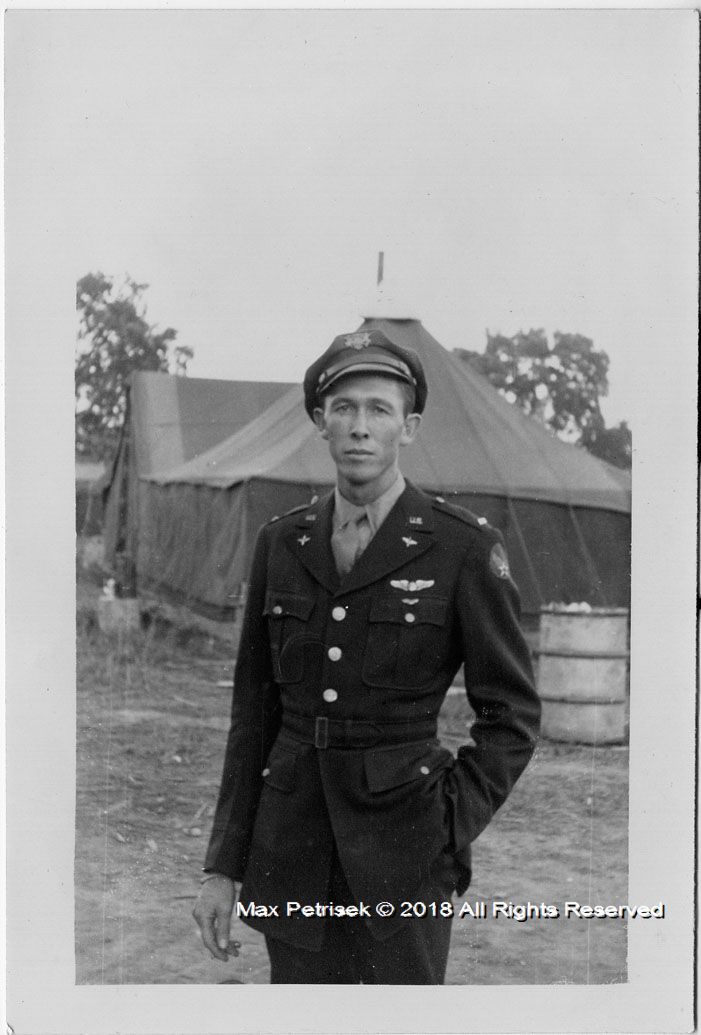

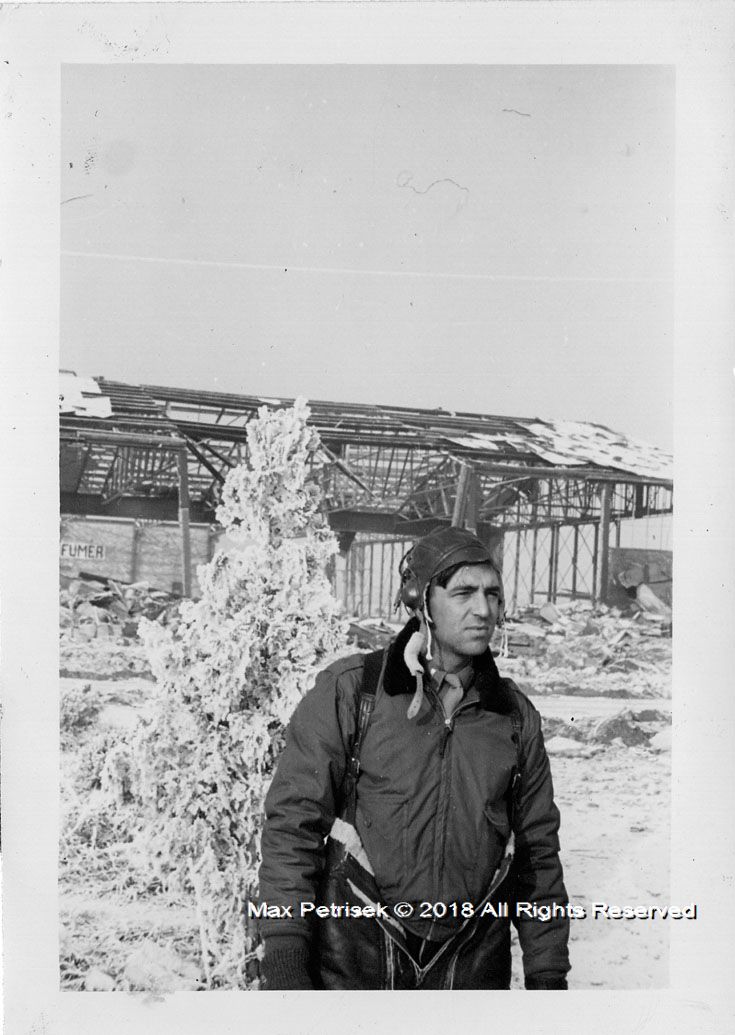

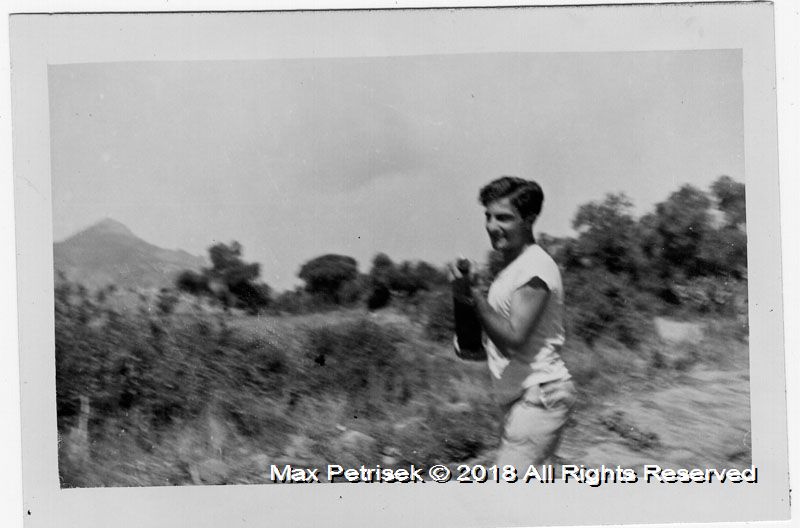

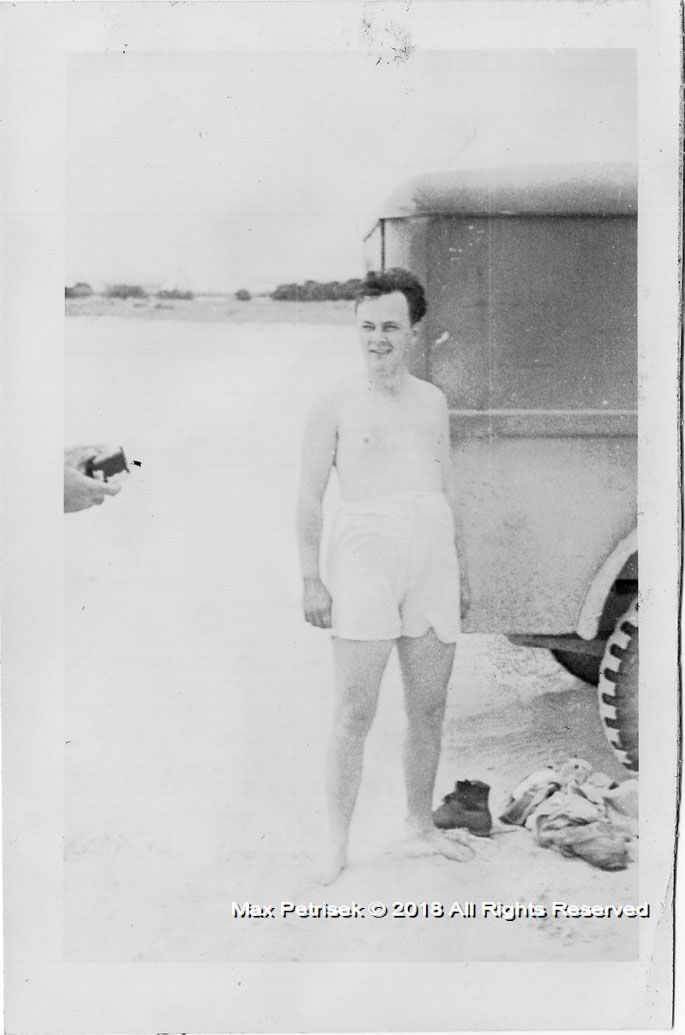

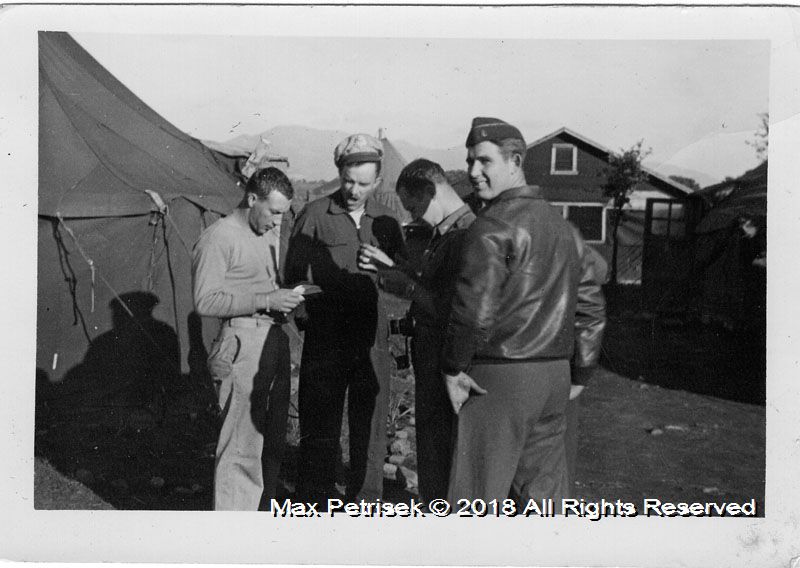

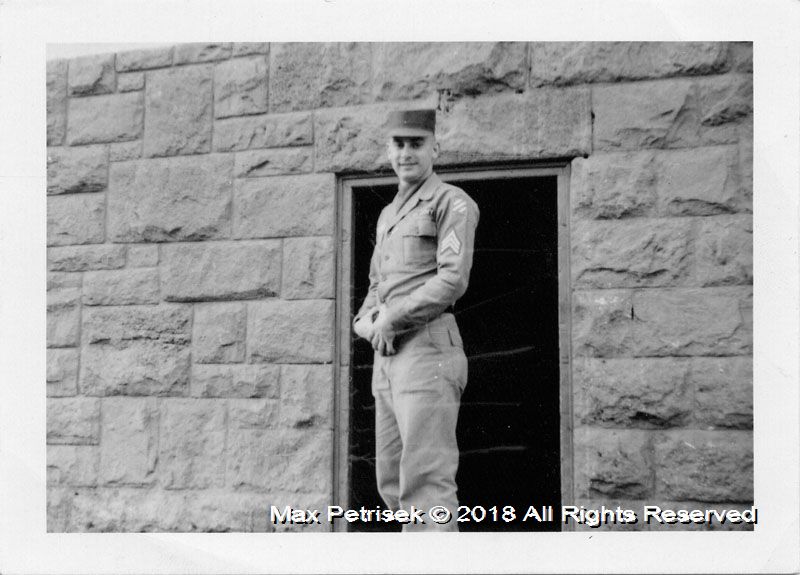

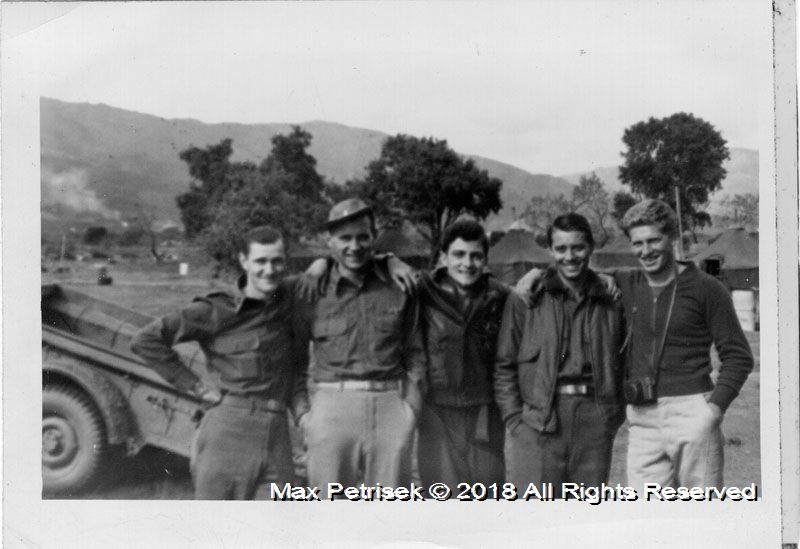

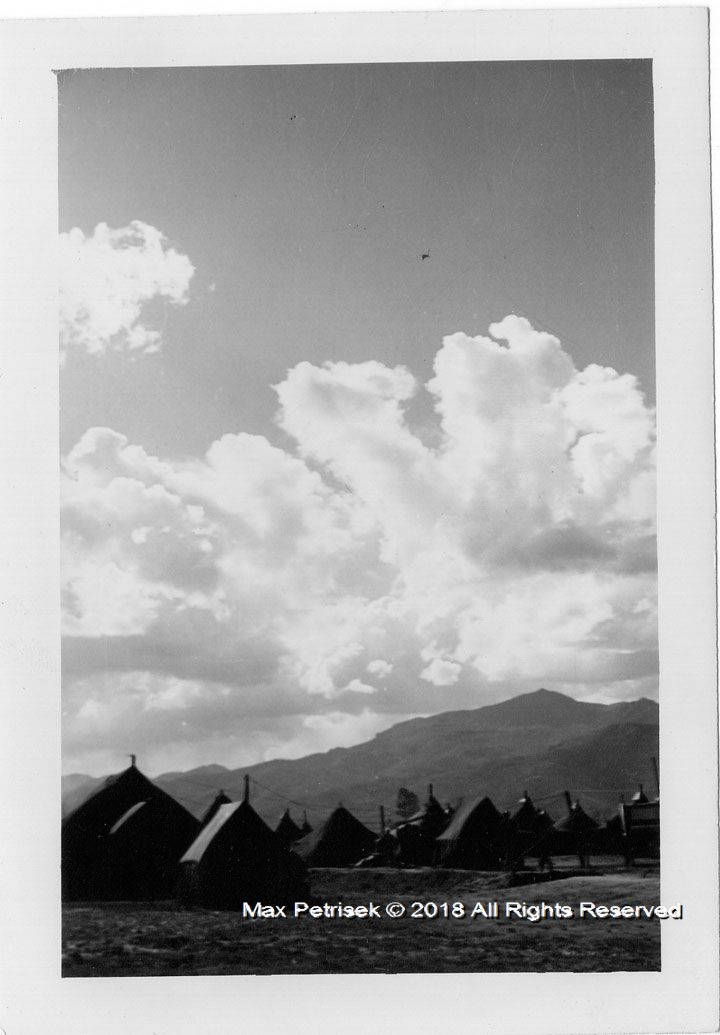

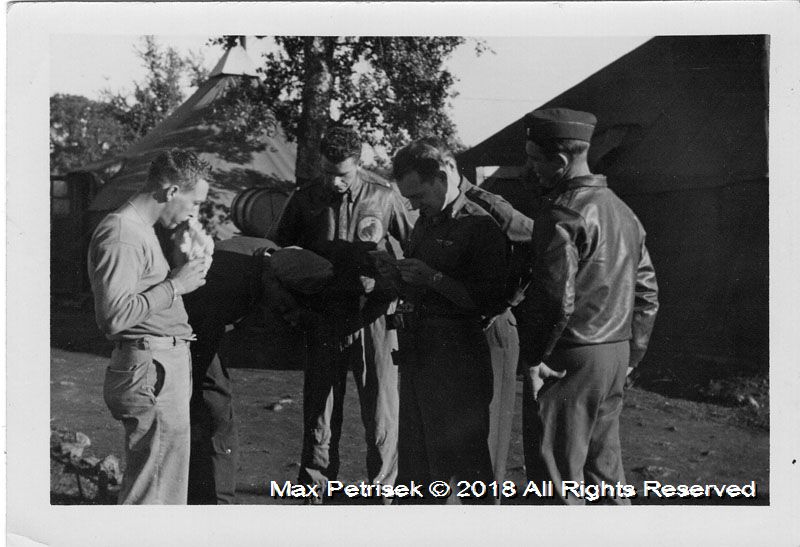

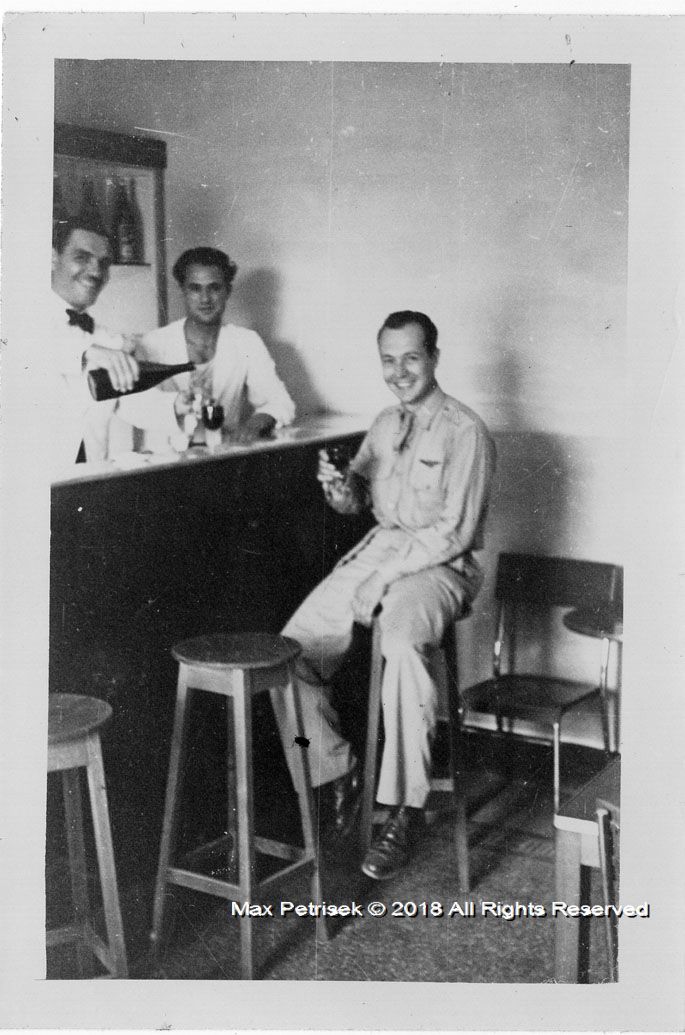

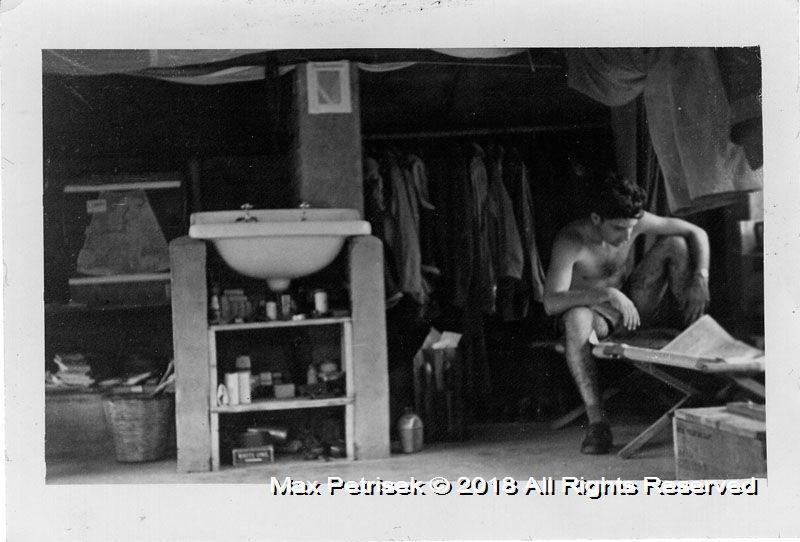

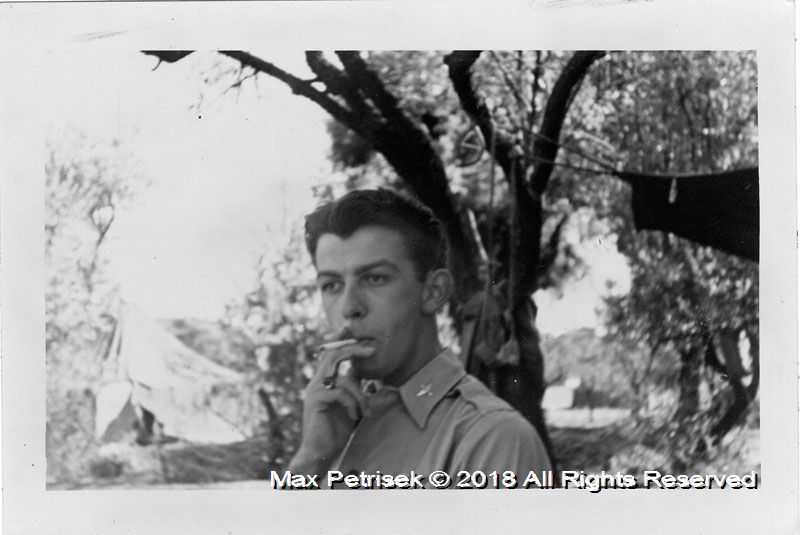

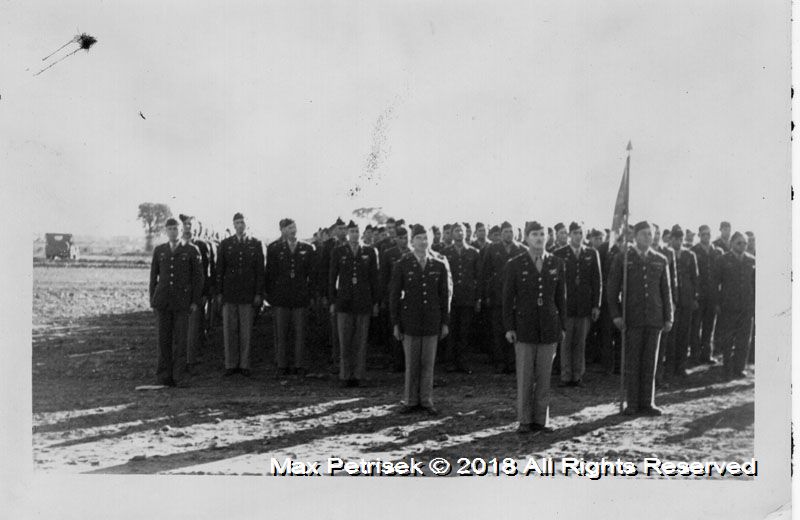

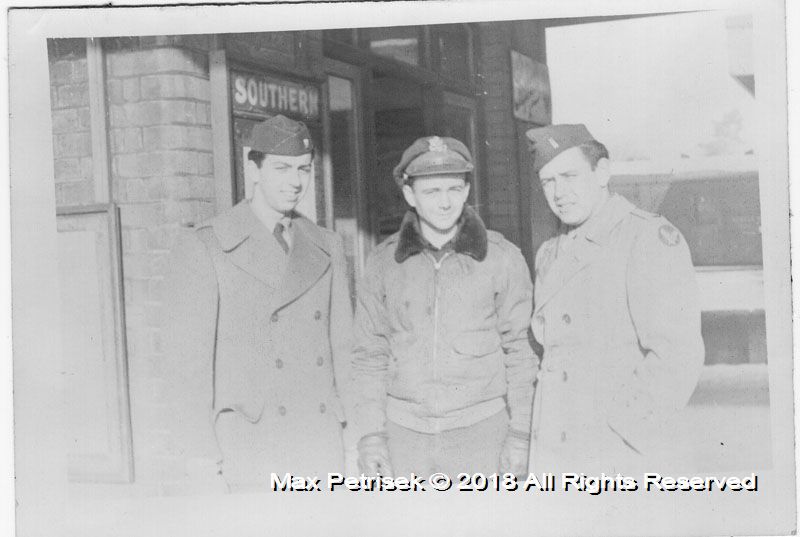

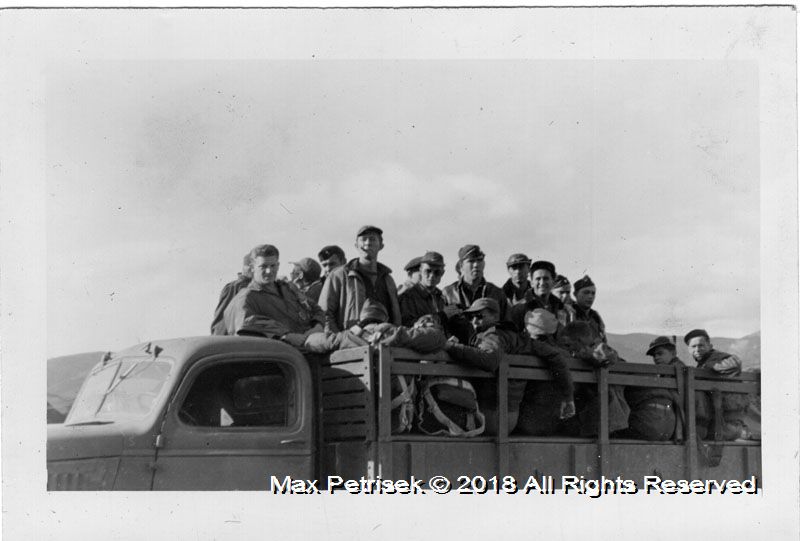

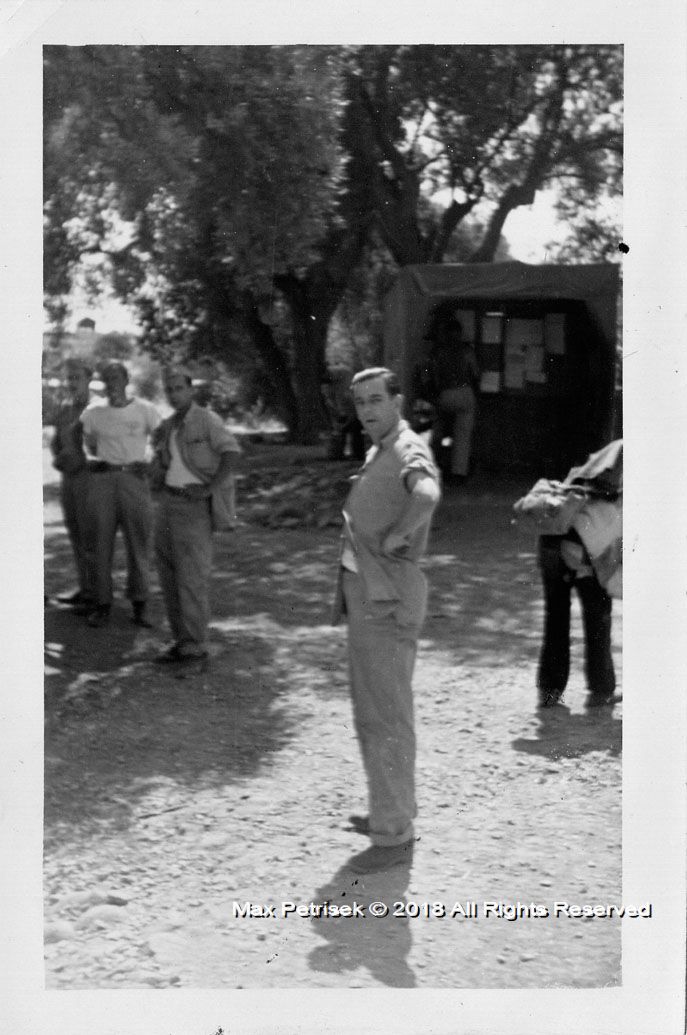

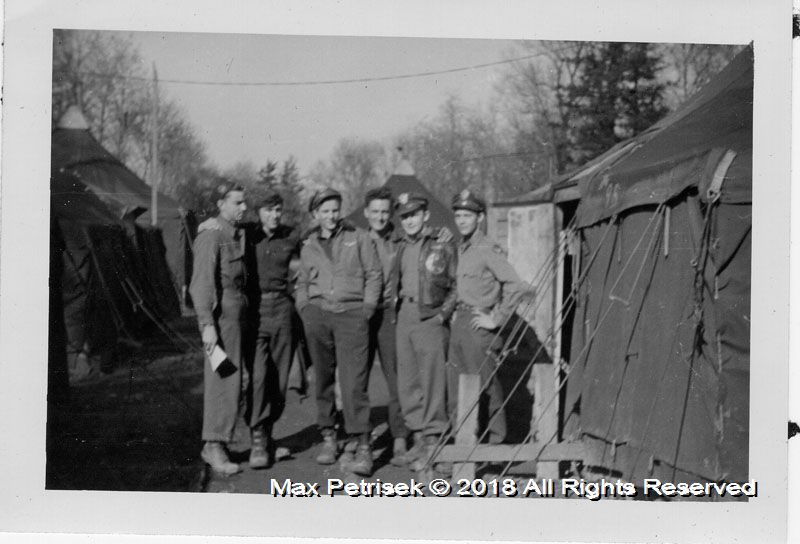

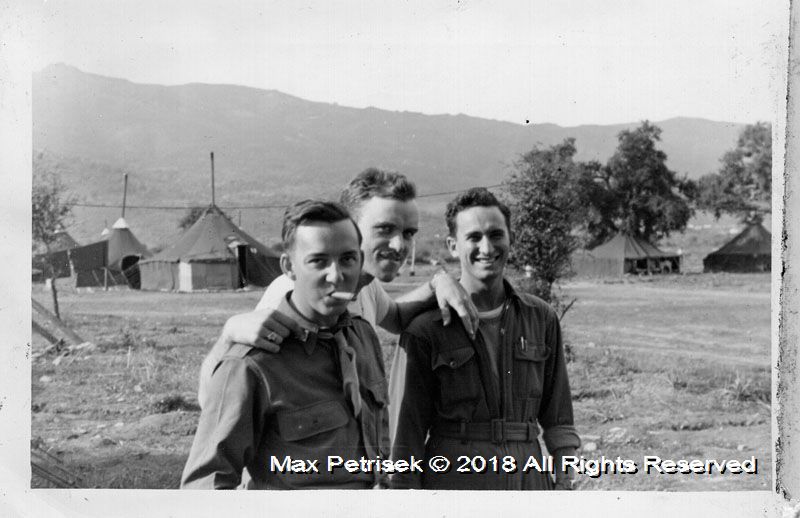

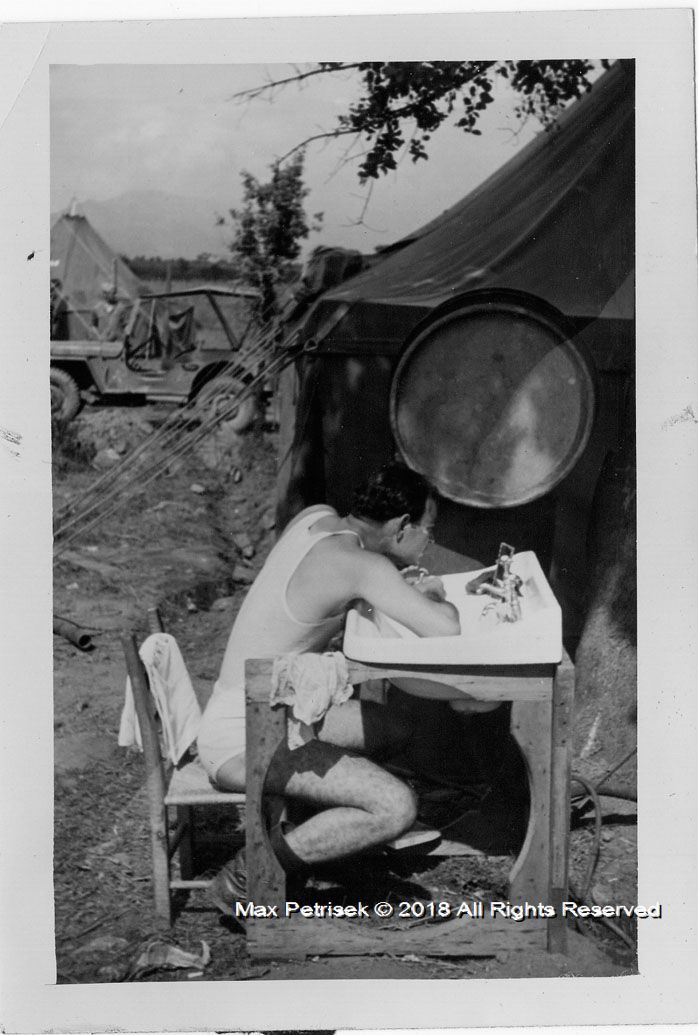

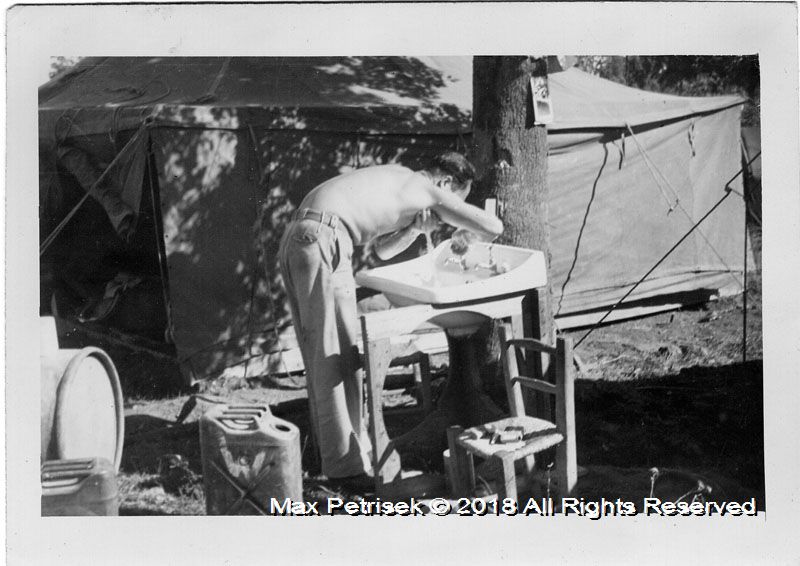

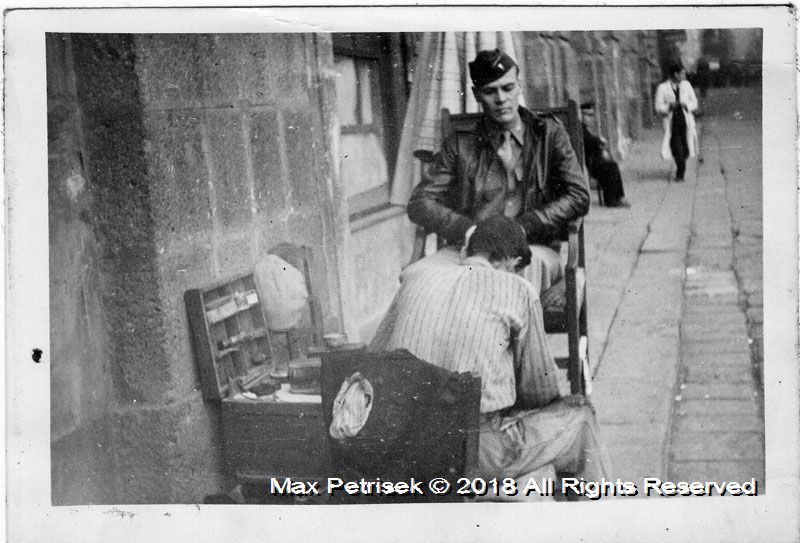

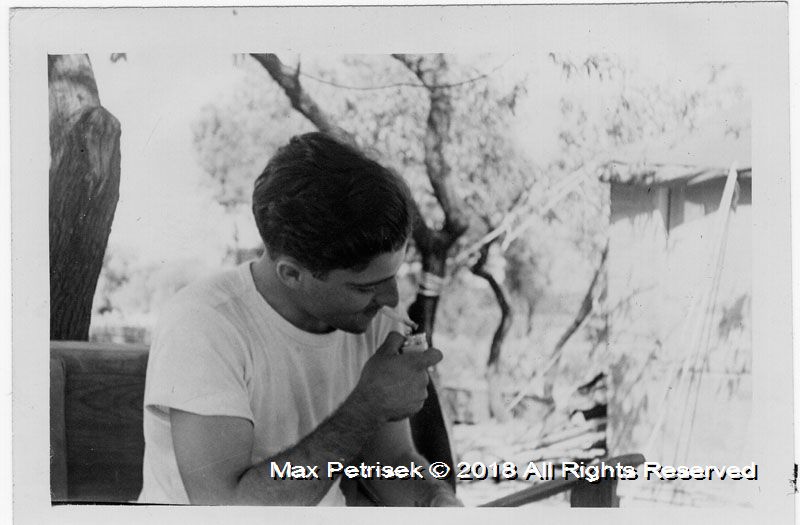

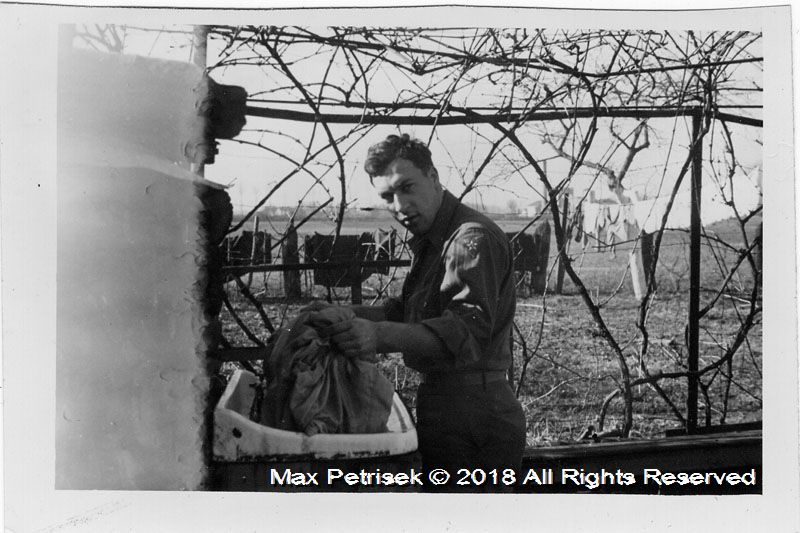

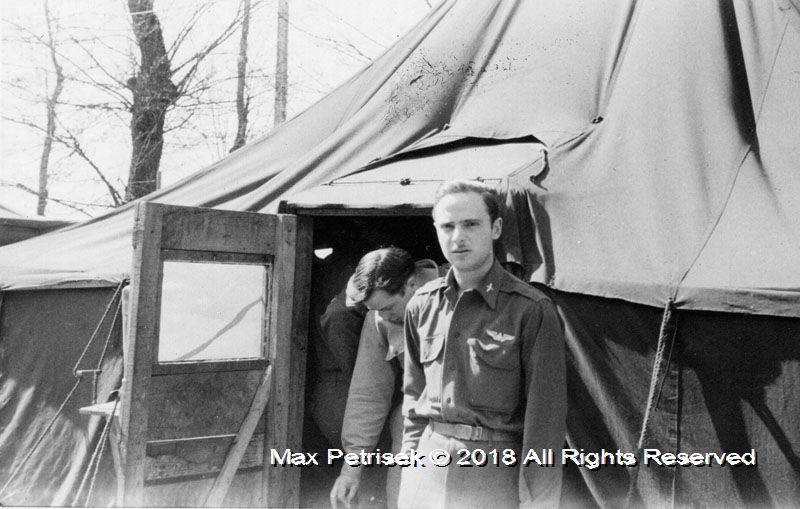

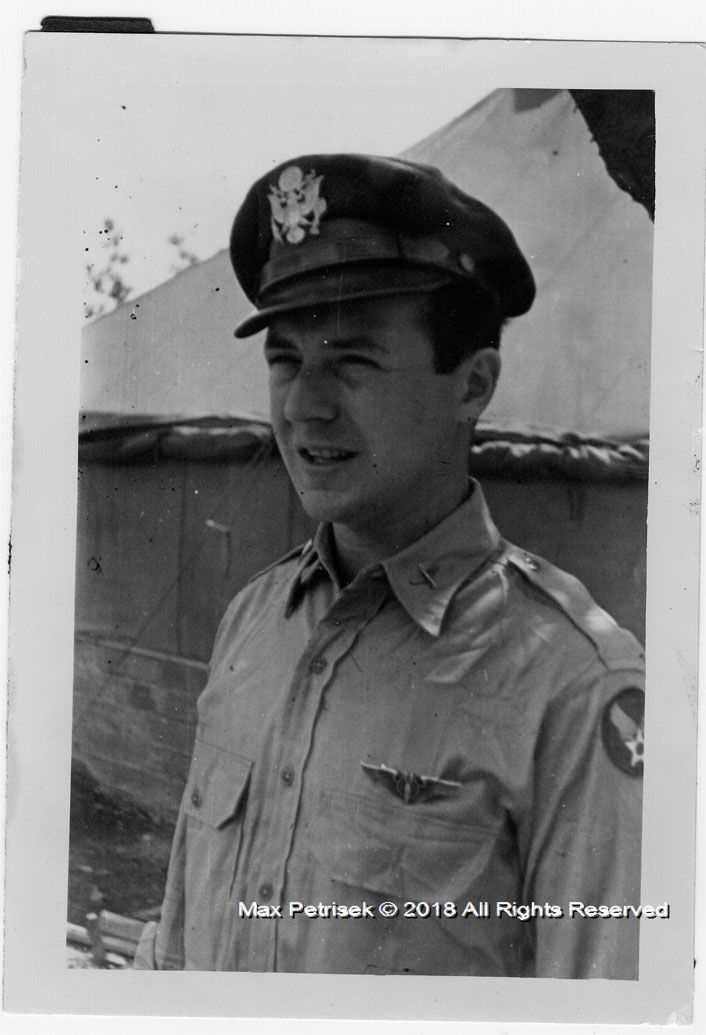

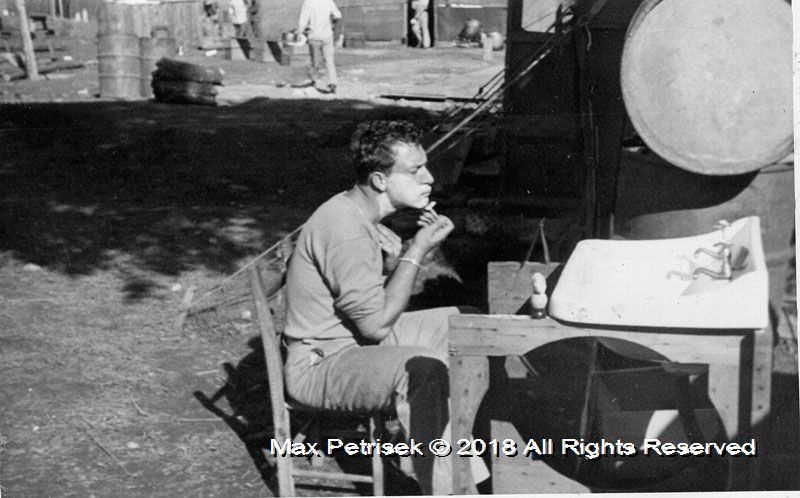

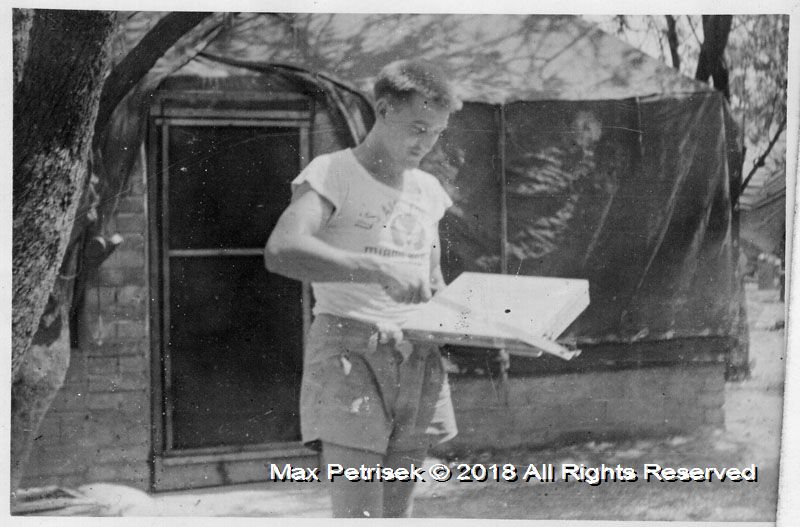

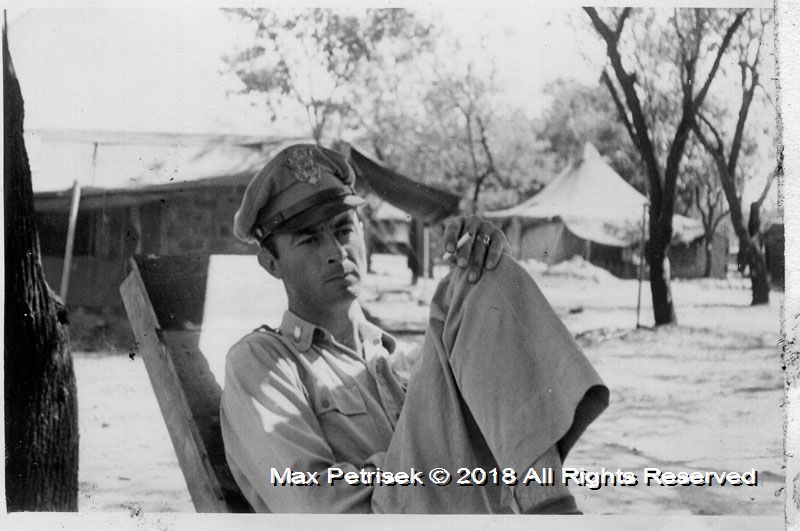

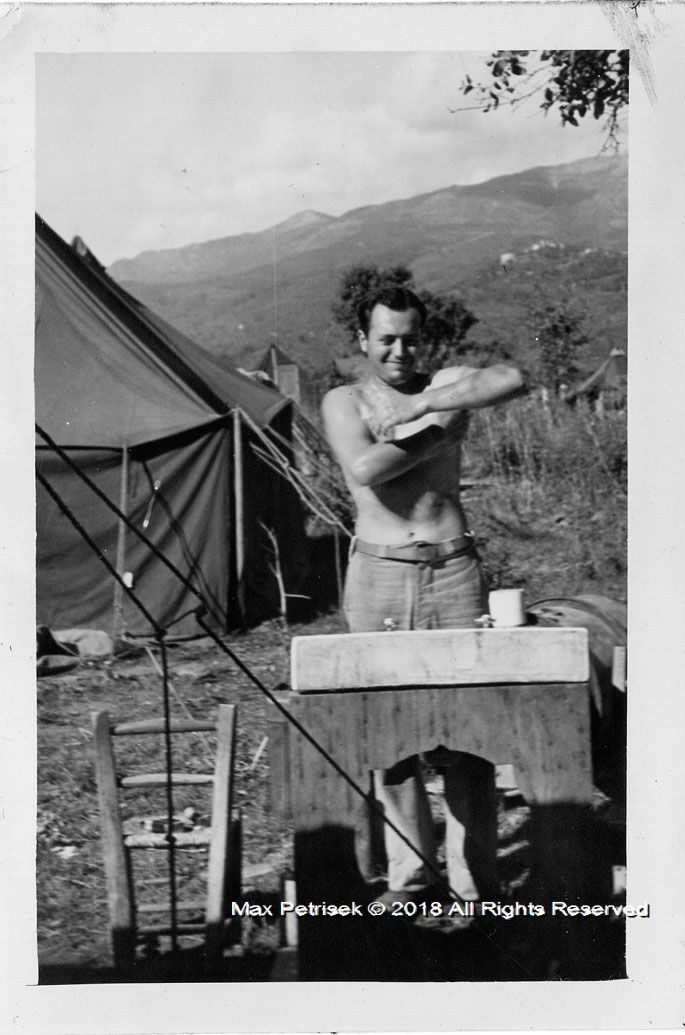

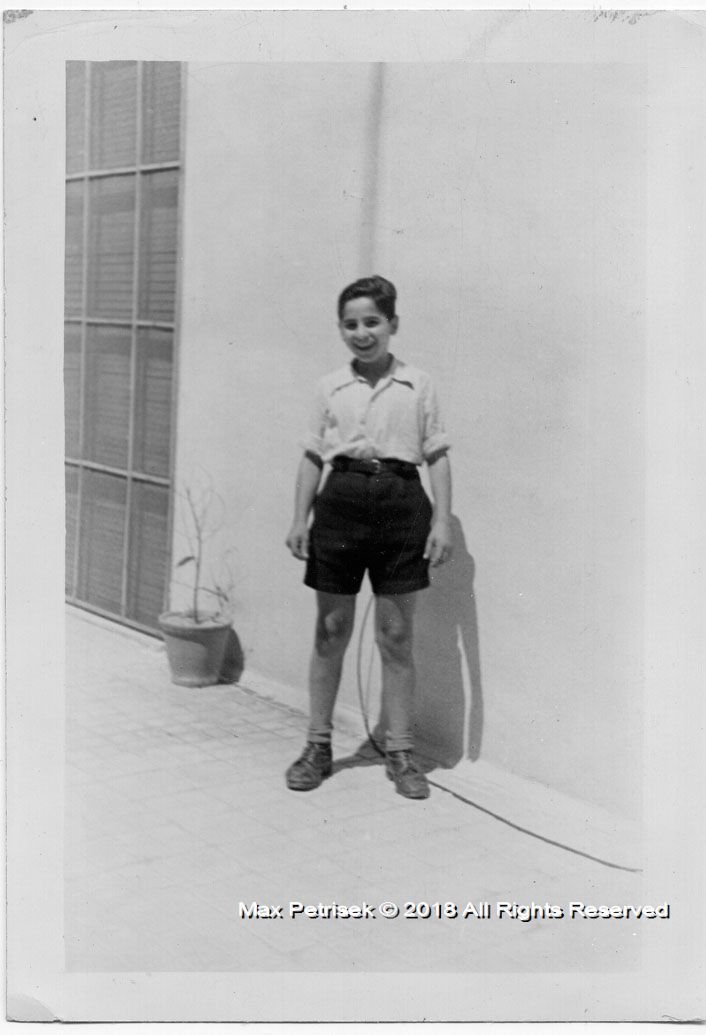

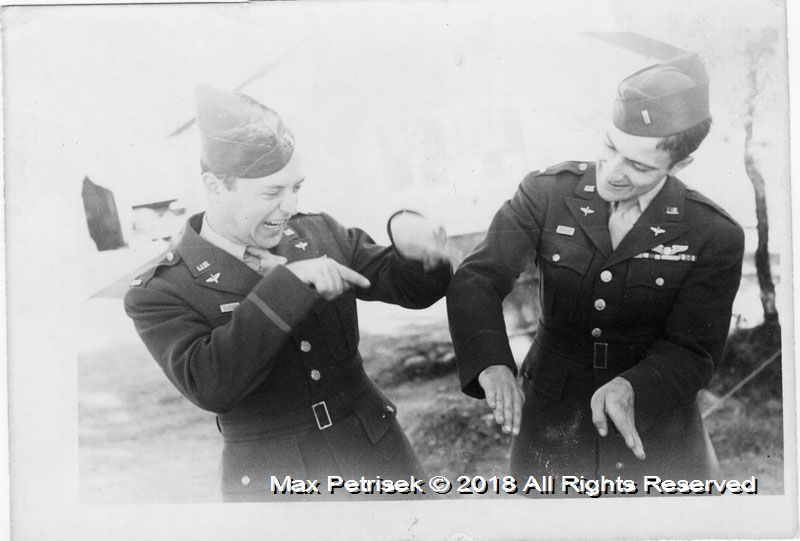

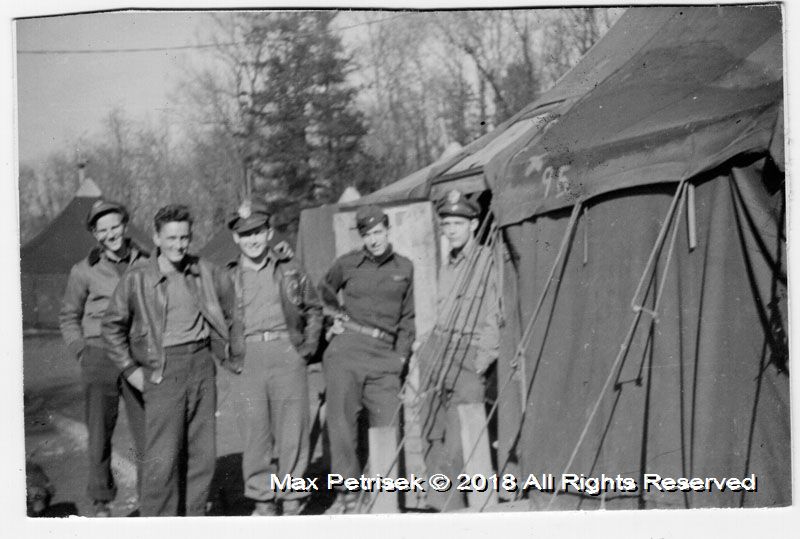

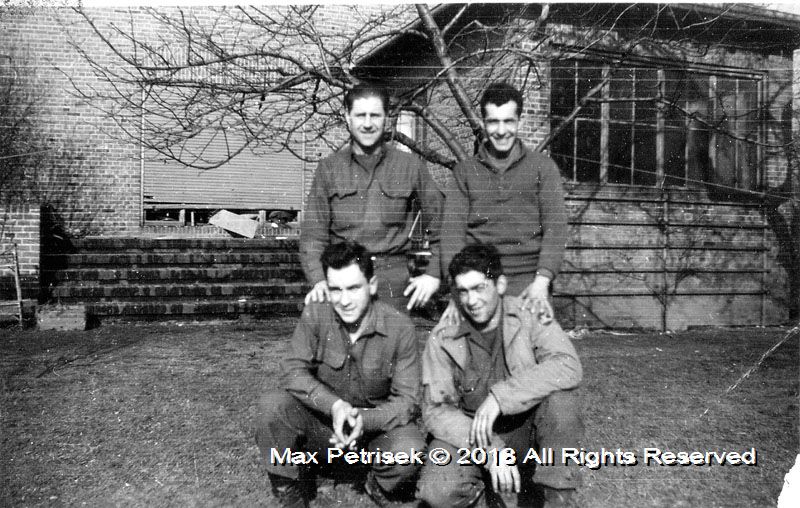

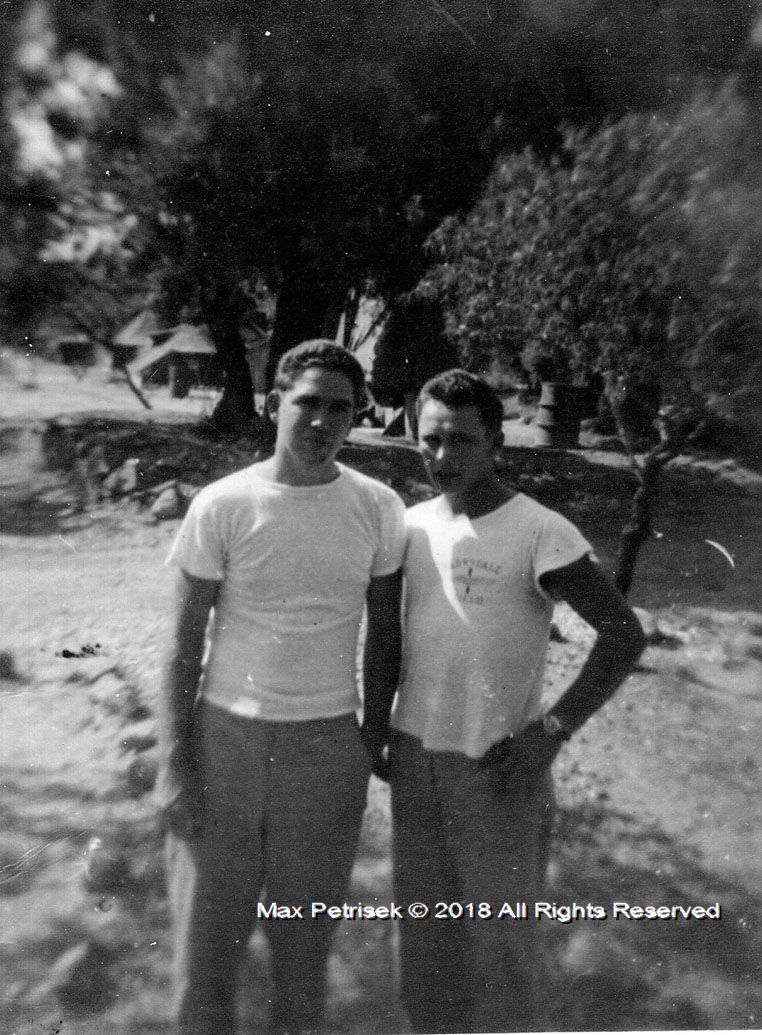

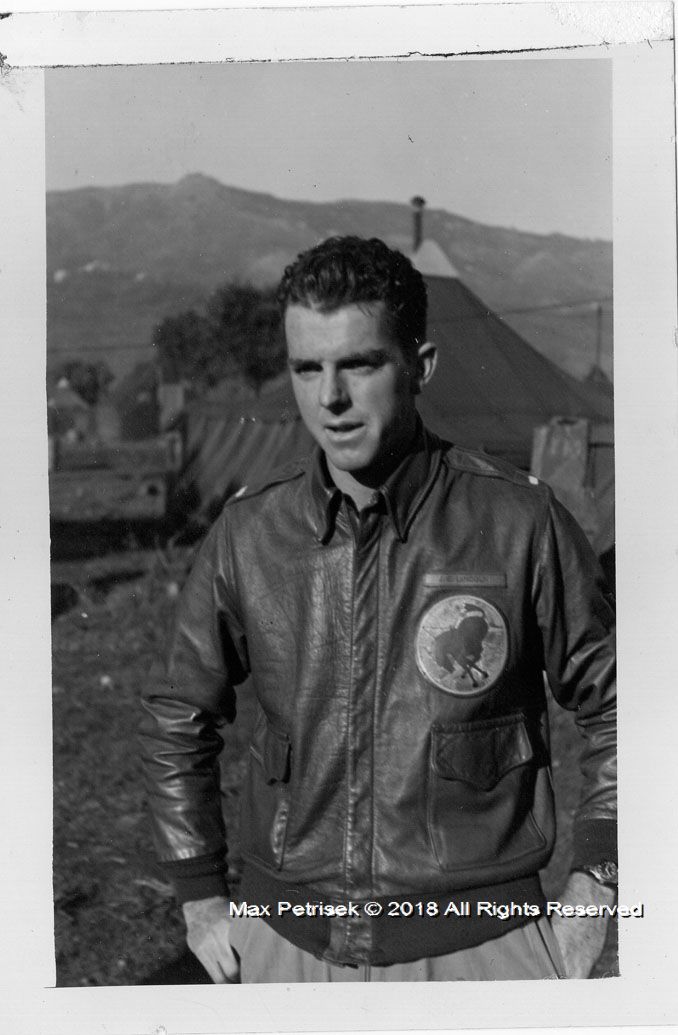

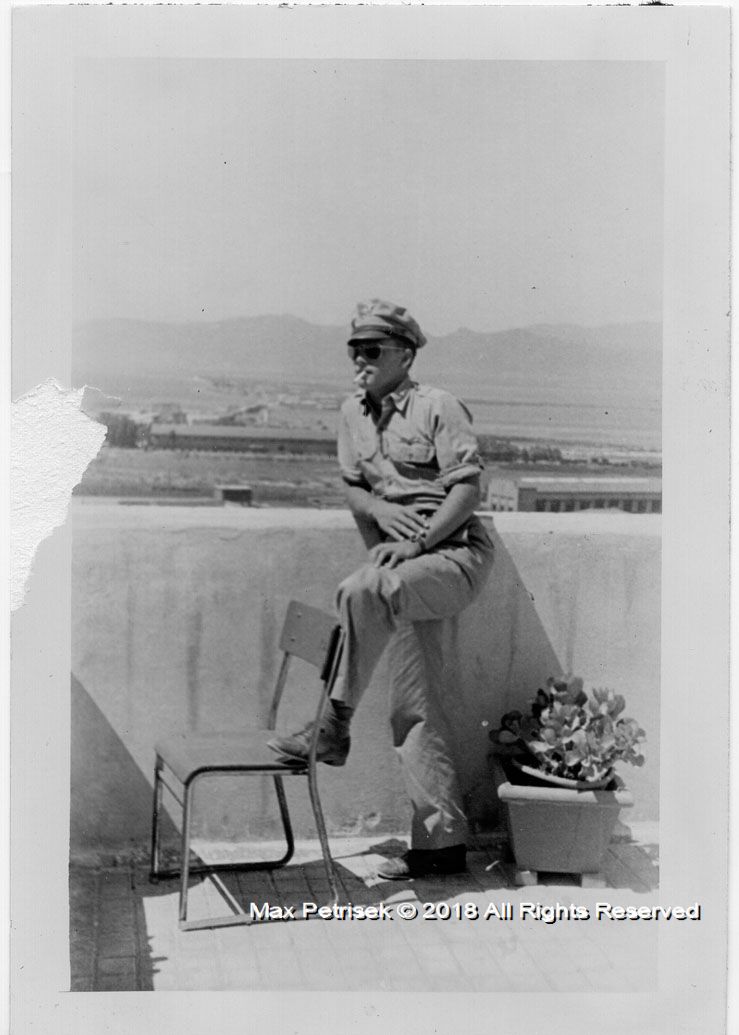

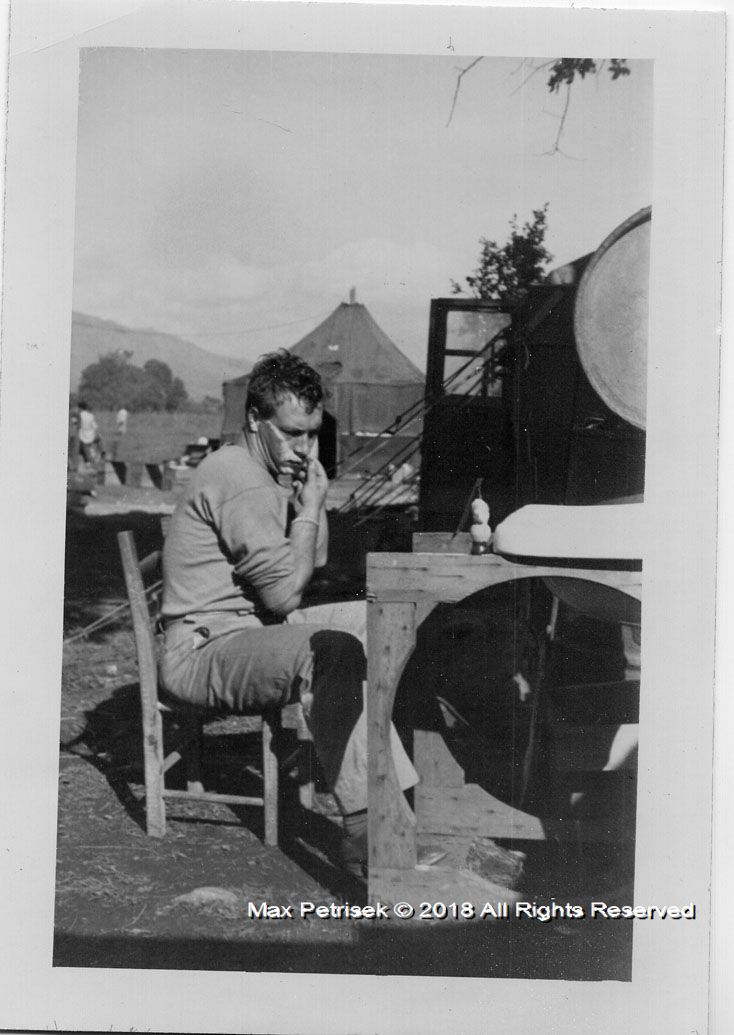

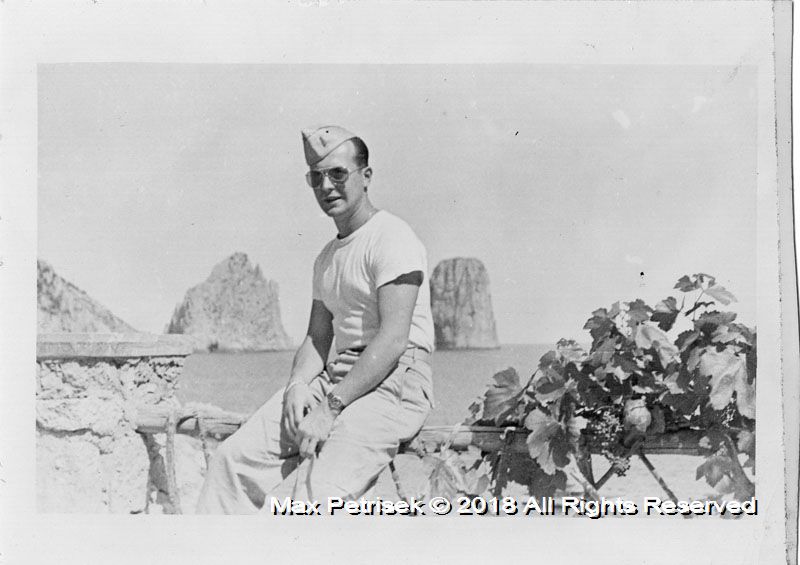

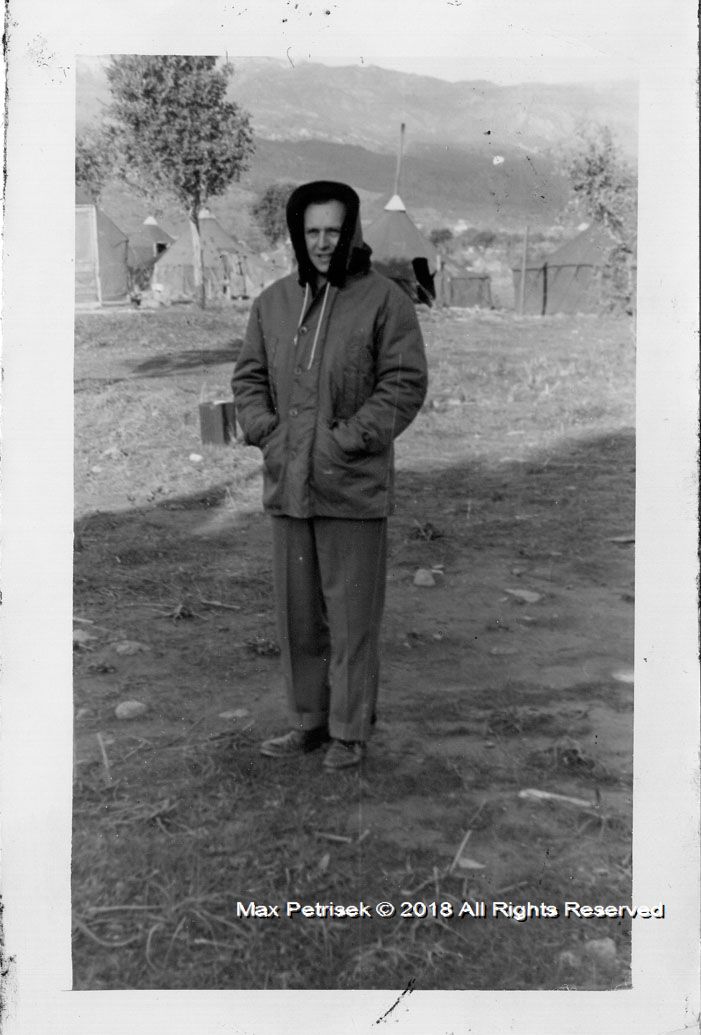

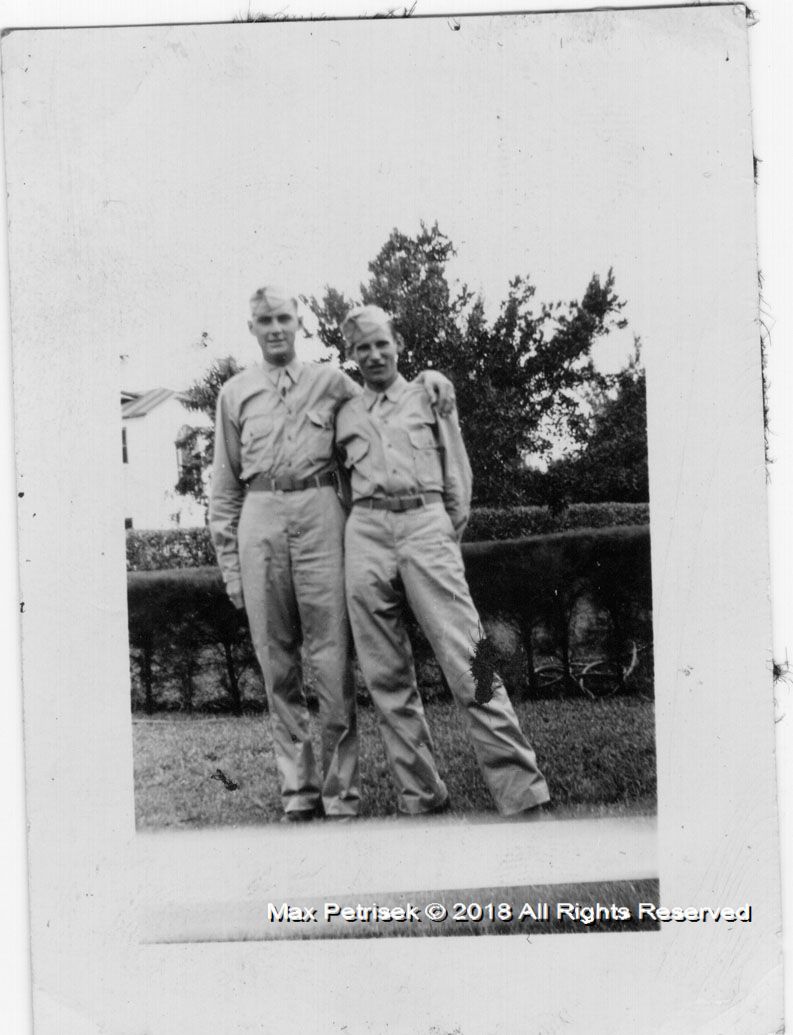

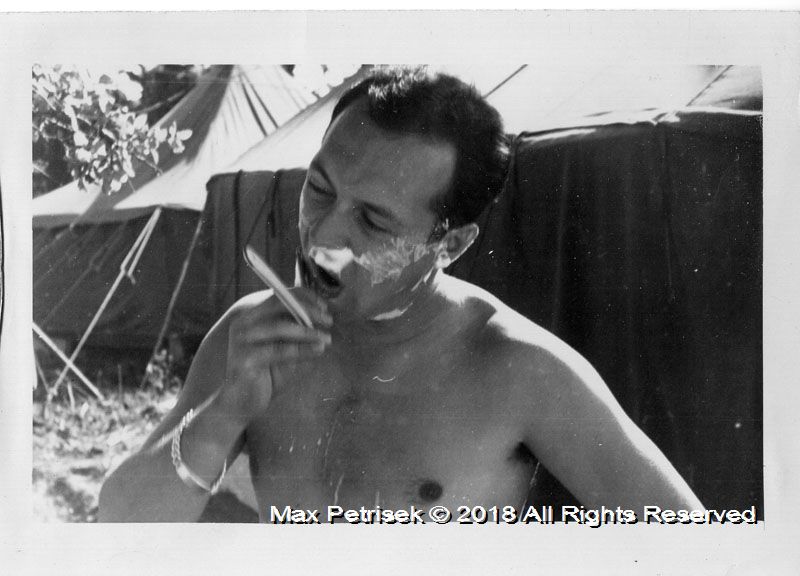

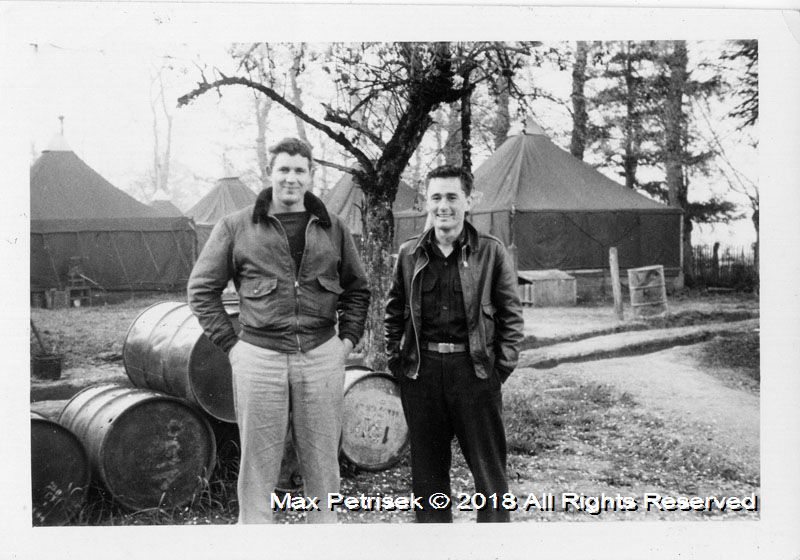

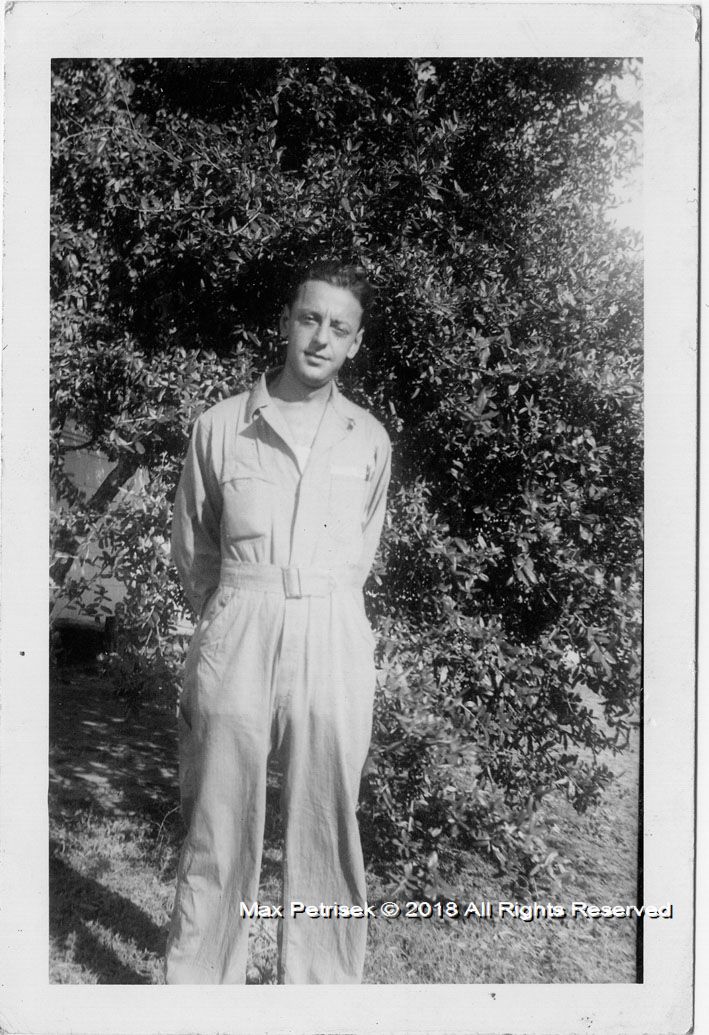

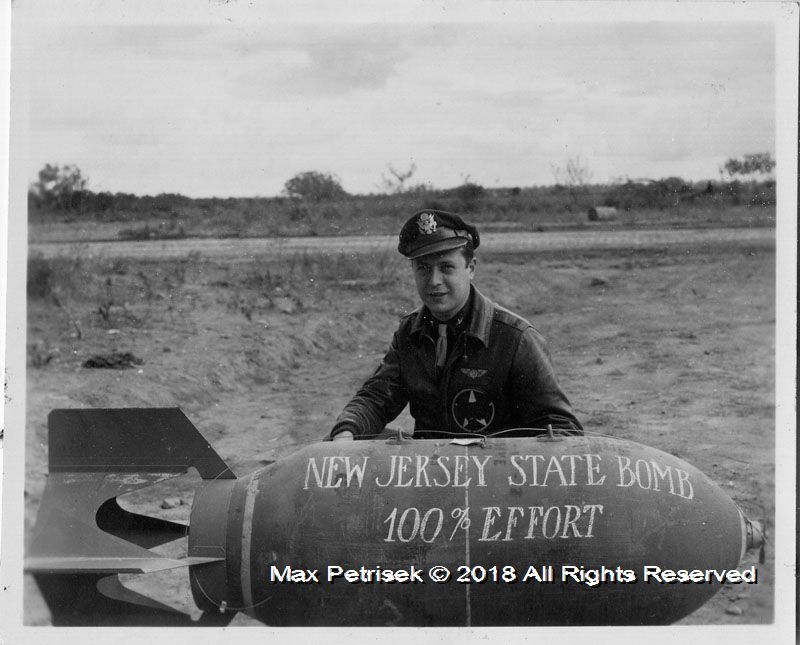

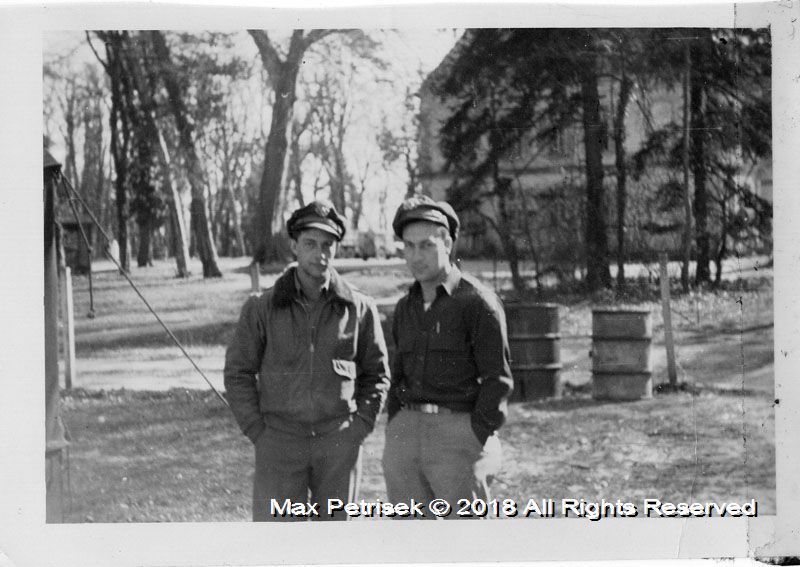

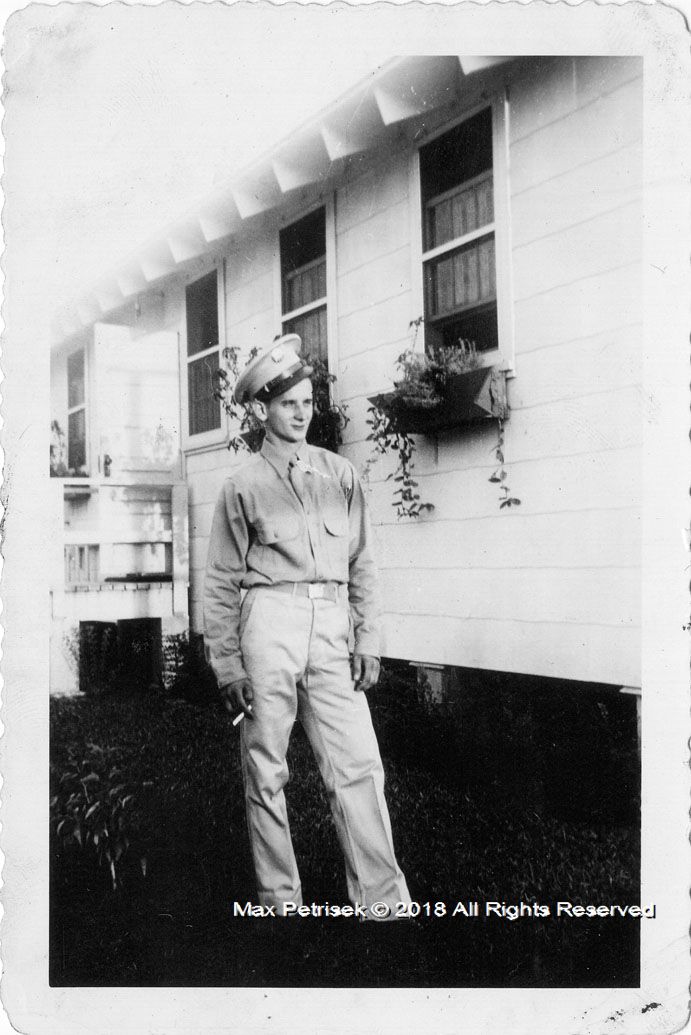

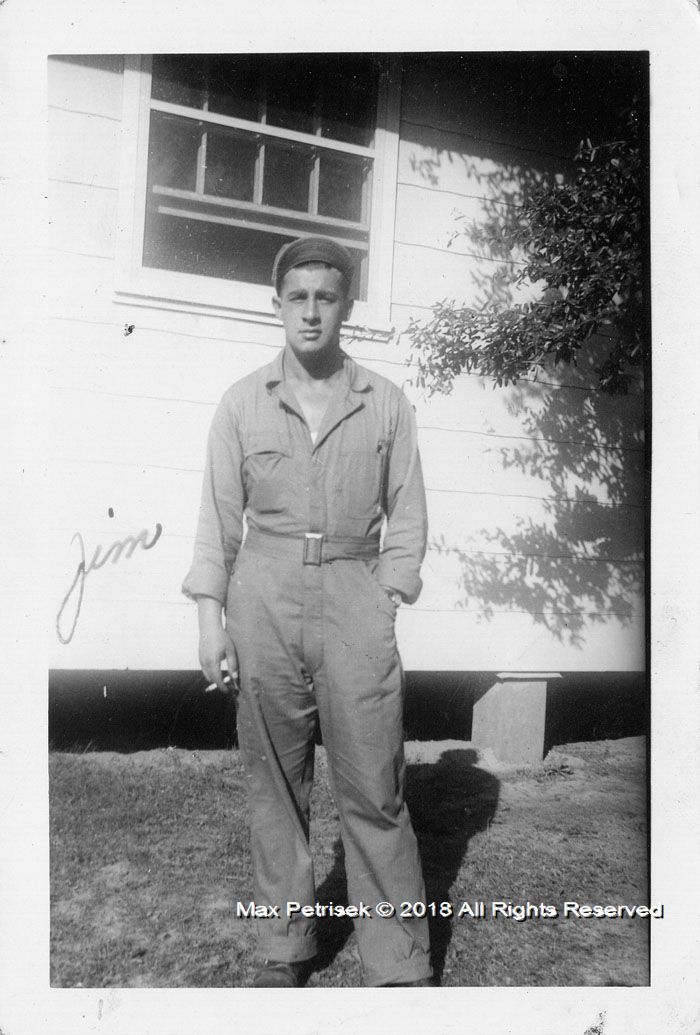

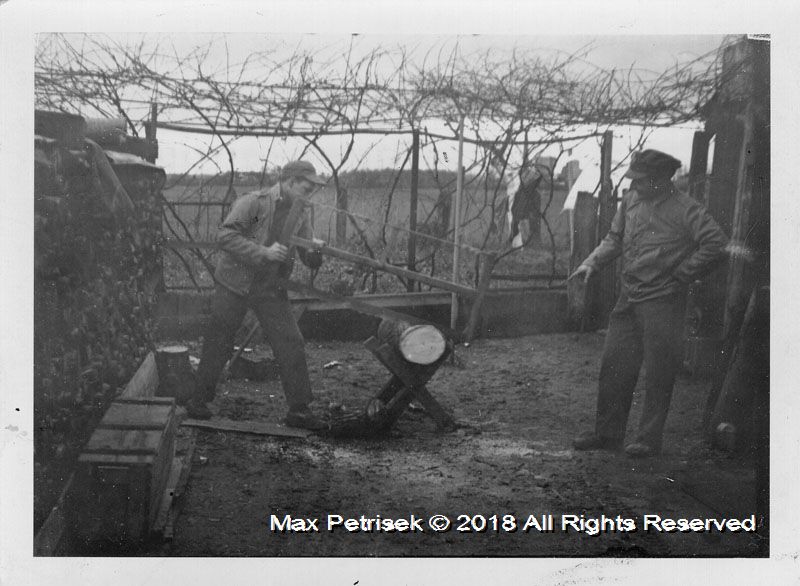

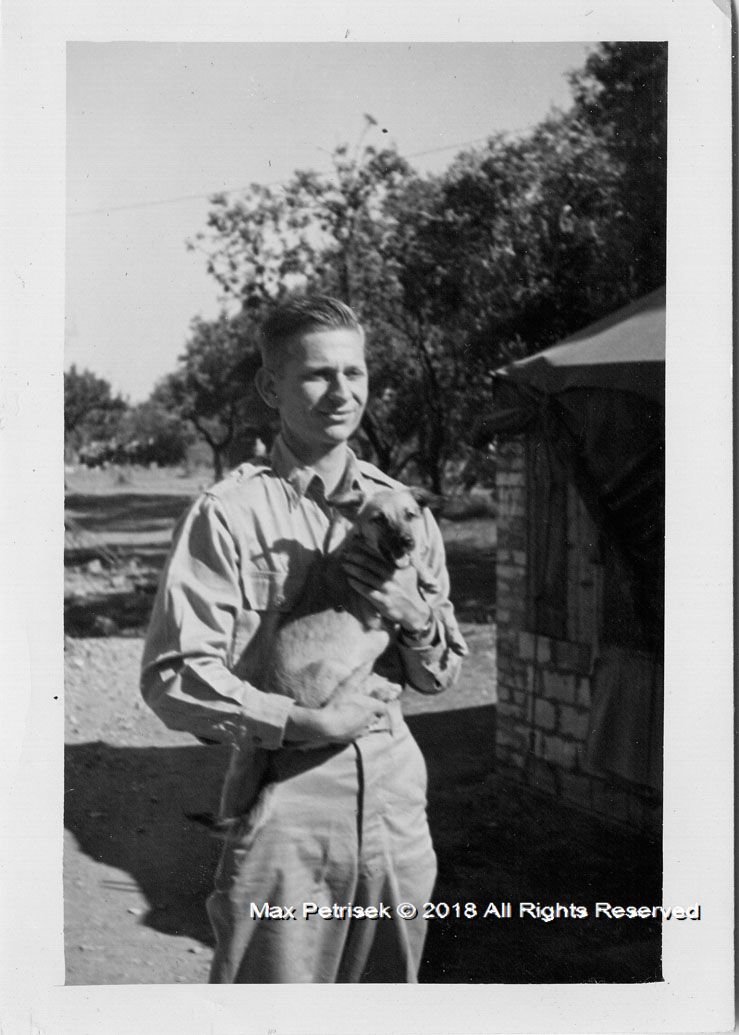

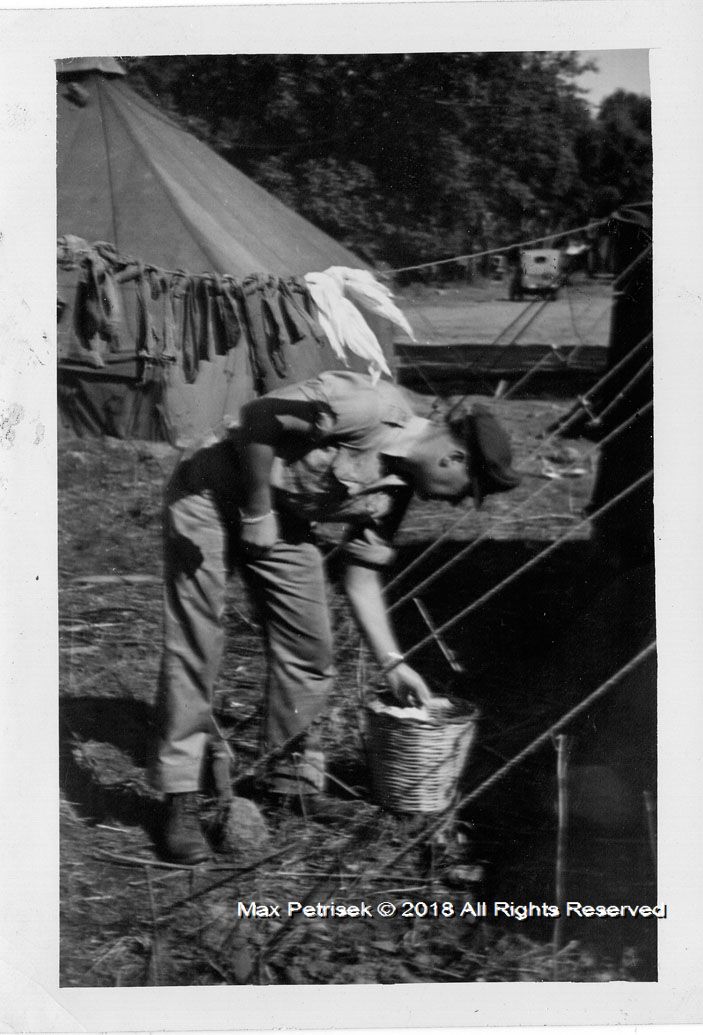

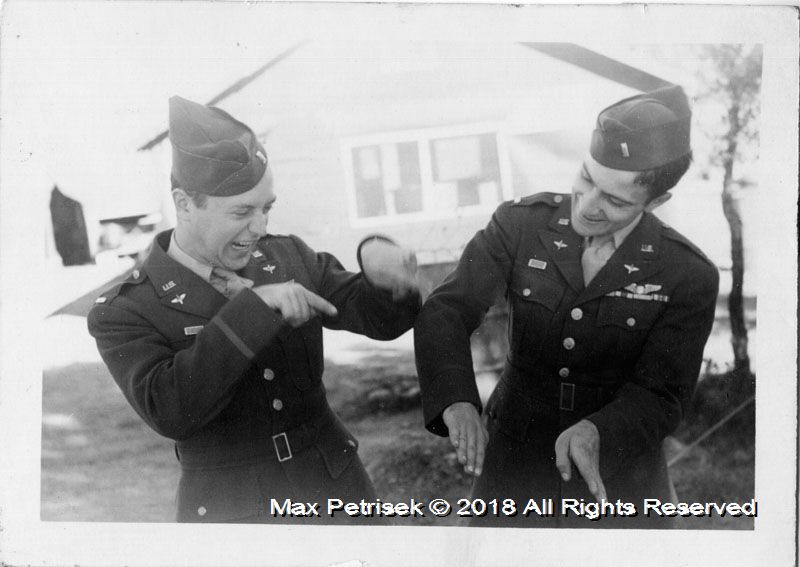

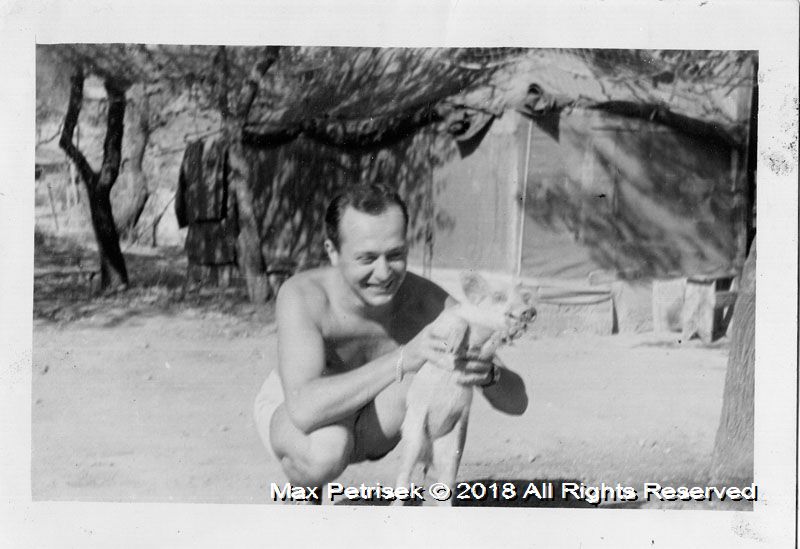

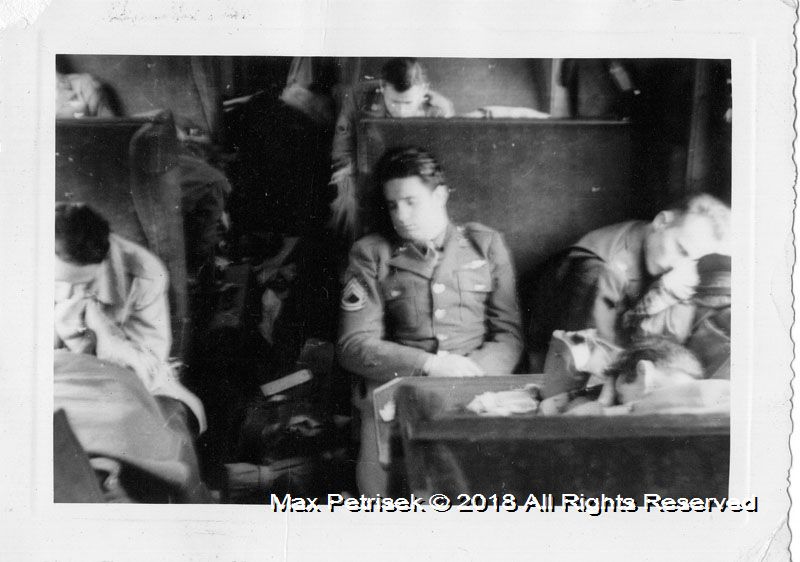

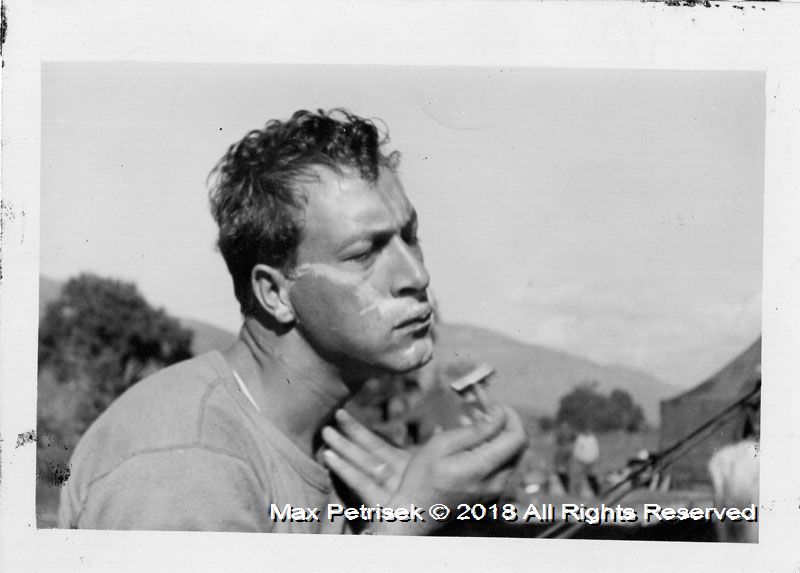

The term, Country Boy, really describes me as I left the farm to a

military life to become “Pete”. Pete was

easier to say than Petrisek for my GI buddies. In my early military

service and career in RCA engineering, I was impressed at the extensive

knowledge and maturity of my peers. My buddies and co-workers were often

from the larger cities, highly mobile and often educated families. They

were graduates of top engineering and military schools. I felt limited by

my experience, as a small-farm boy from the harsh coal mine area and small

town high school and college. This would place me at the lower scale of

wisdom and education, a maverick or bushman among the more interesting,

worldly and talented peers. Thus, I was driven to work harder just to keep

in contention.

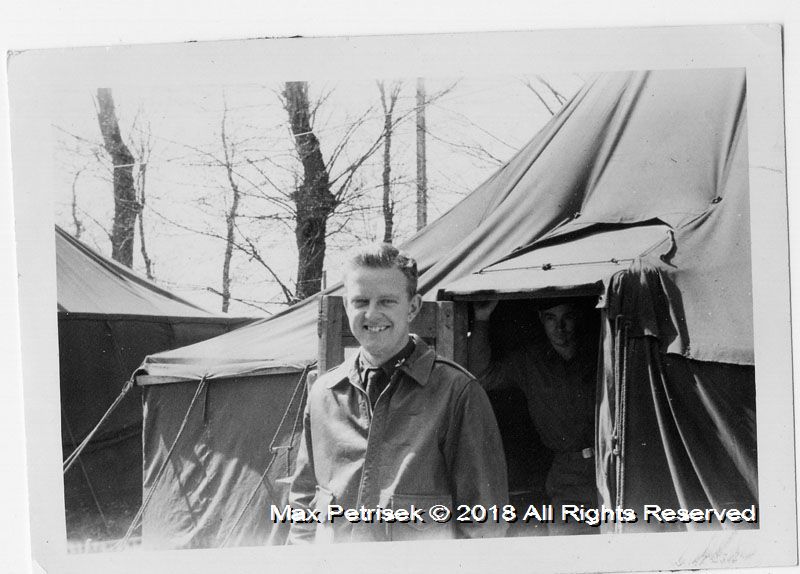

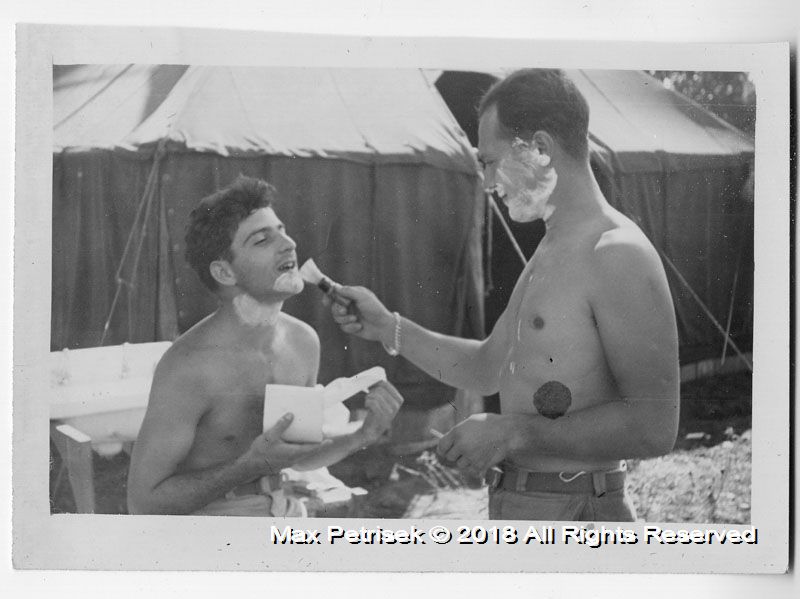

I learned to listen, continue my studies and completely commit myself to

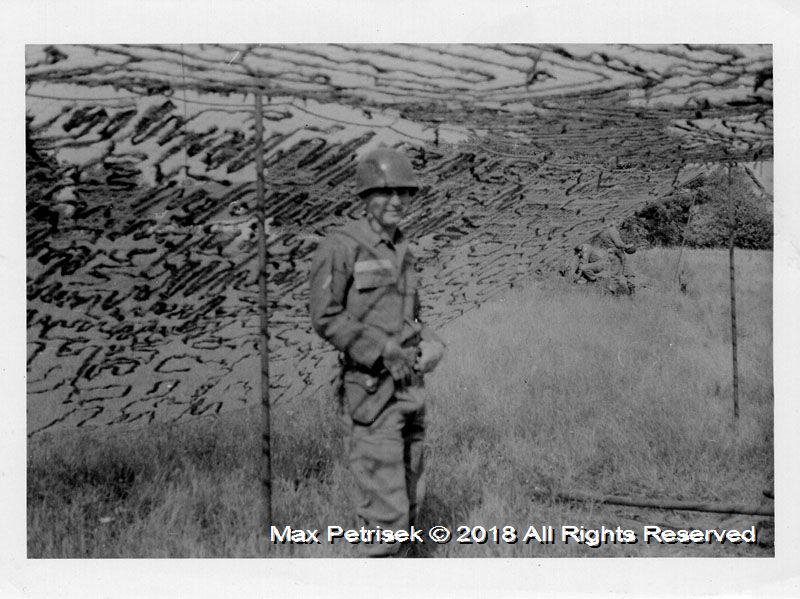

compete with the “head start” group. I had the instinct of a survivor and

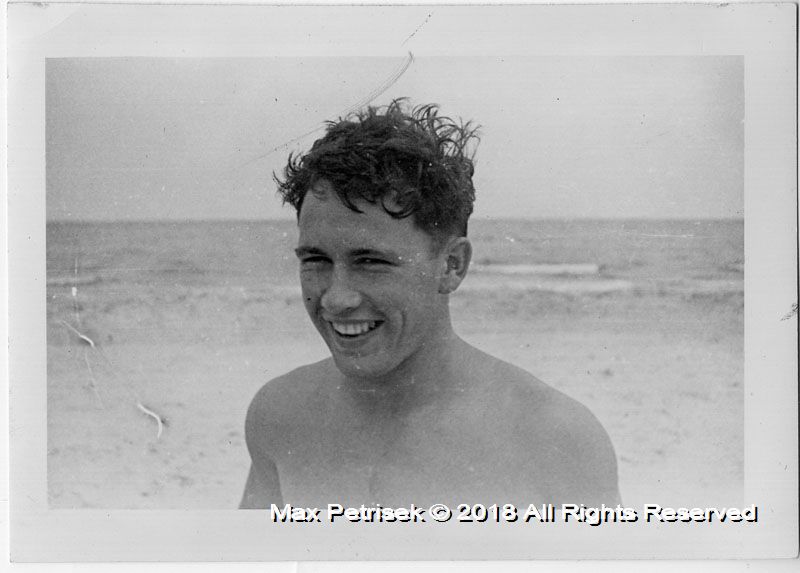

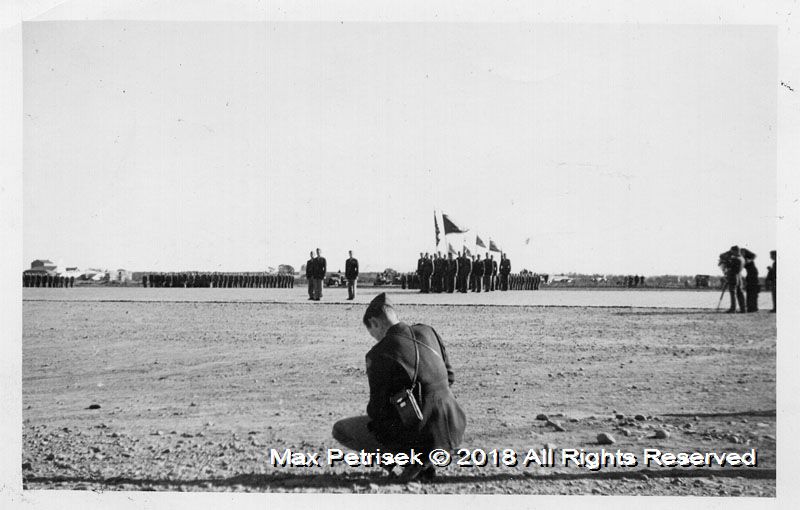

to become an achiever. Of those beginning pilot training, approximately

seventy five percent never made it to the finish line, and that was, to

return home after a tour of combat. This I did, prior to my twenty-first

birthday.

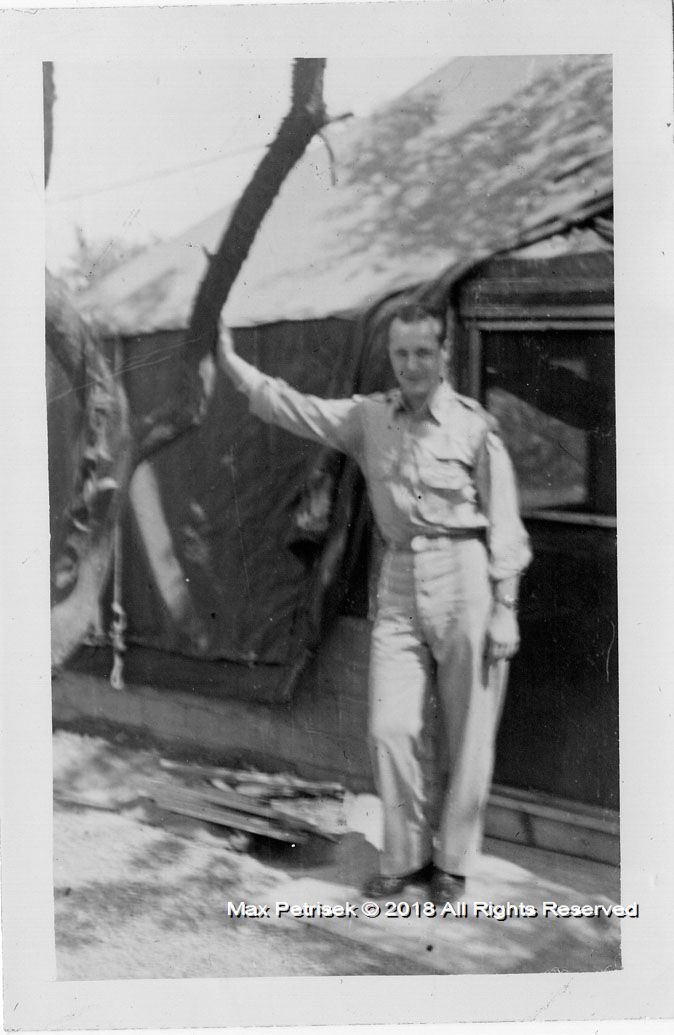

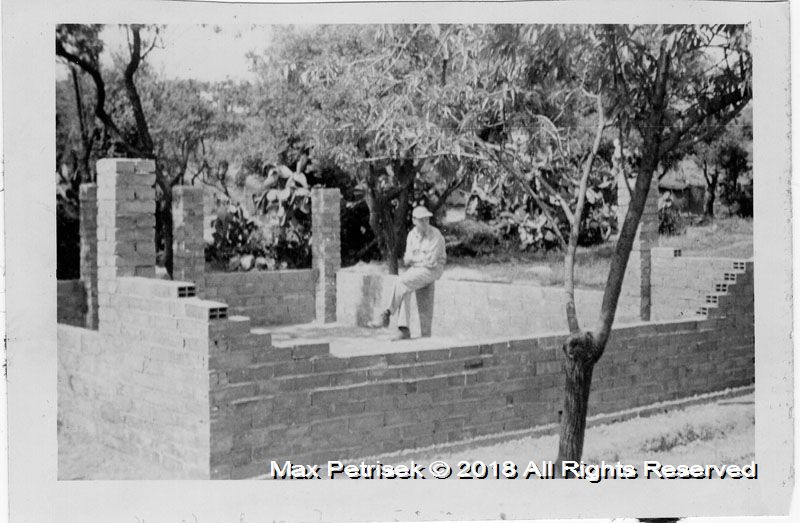

I do feel lucky now, to be normal and to have a wonderful family. I am

over eighty, feeling worldly for the experiences in my work career and

involvement in WWII.

The world of cyberspace technology and the Age of Information hold great

excitement and enjoyment for me. I am privileged to live in a free country

to partake in the pleasures of time spent with my large family. My family

is in the fast track of instant gratification as to entertainment and

achievement. They are very successful and thoroughly committed to the work

ethic. Their lack of free time and being so involved is a concern for me

as a parent. They may never have time to read all of my story and

understandably so.

I have never, during my raising of my children, told them my experiences

of the war, so now I am ready to tell my story. My satisfaction for

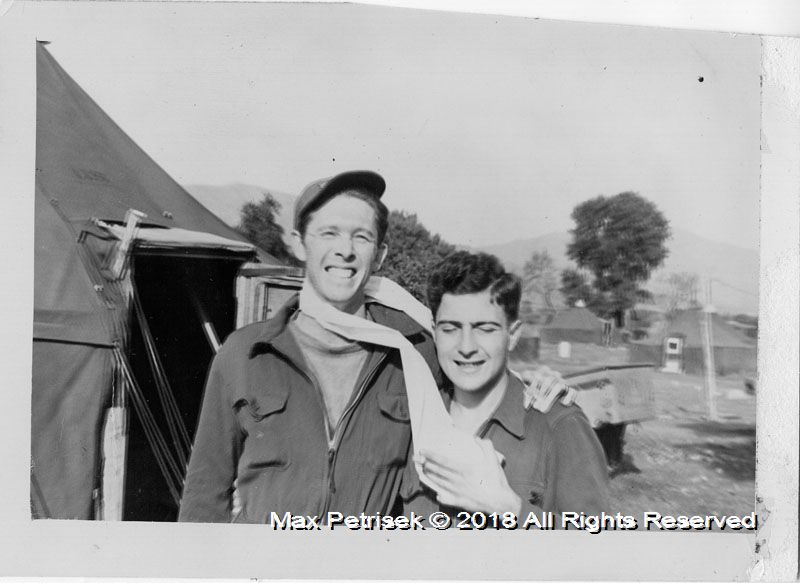

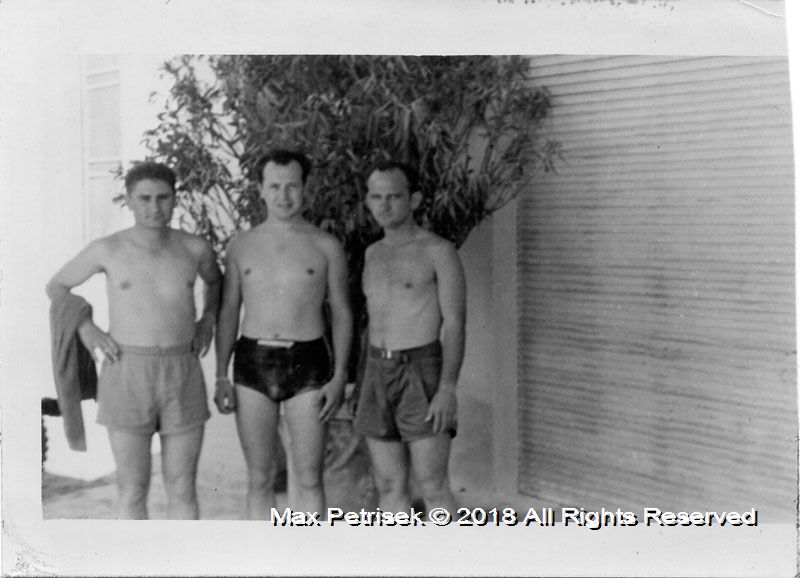

writing this story comes from taking the time to acknowledge the

contribution of my family and GI buddies who gave so much to win WWII. I

could not write this story to impress others or build up my ego.

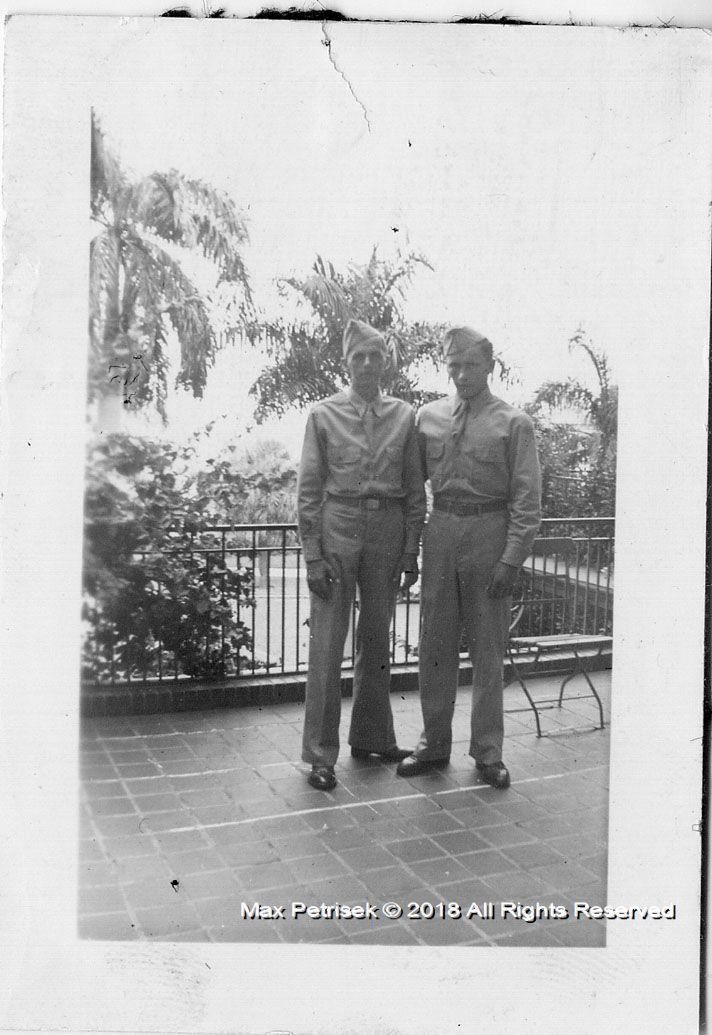

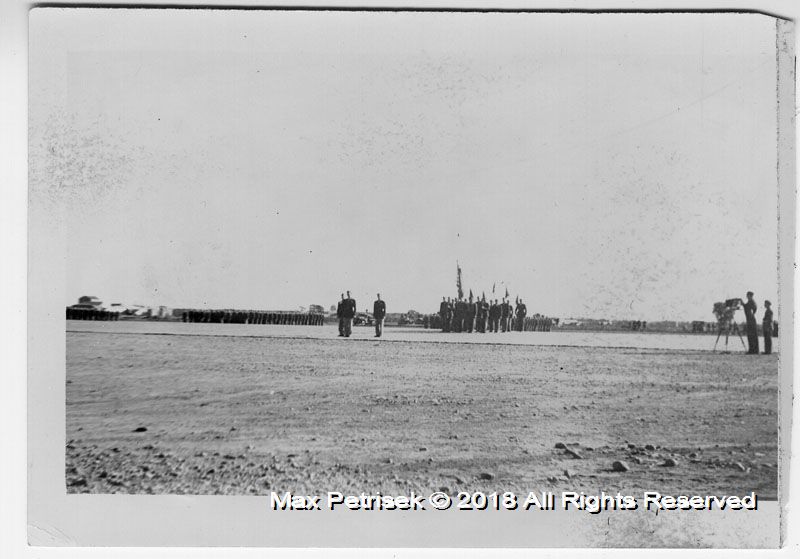

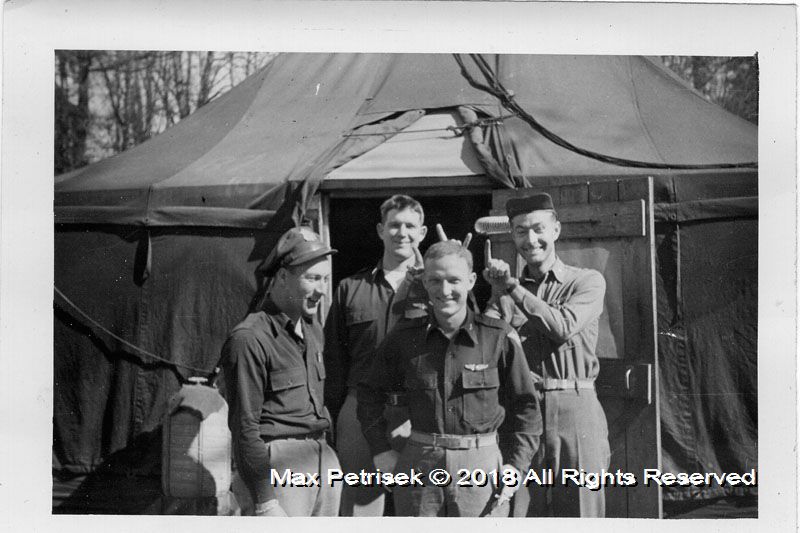

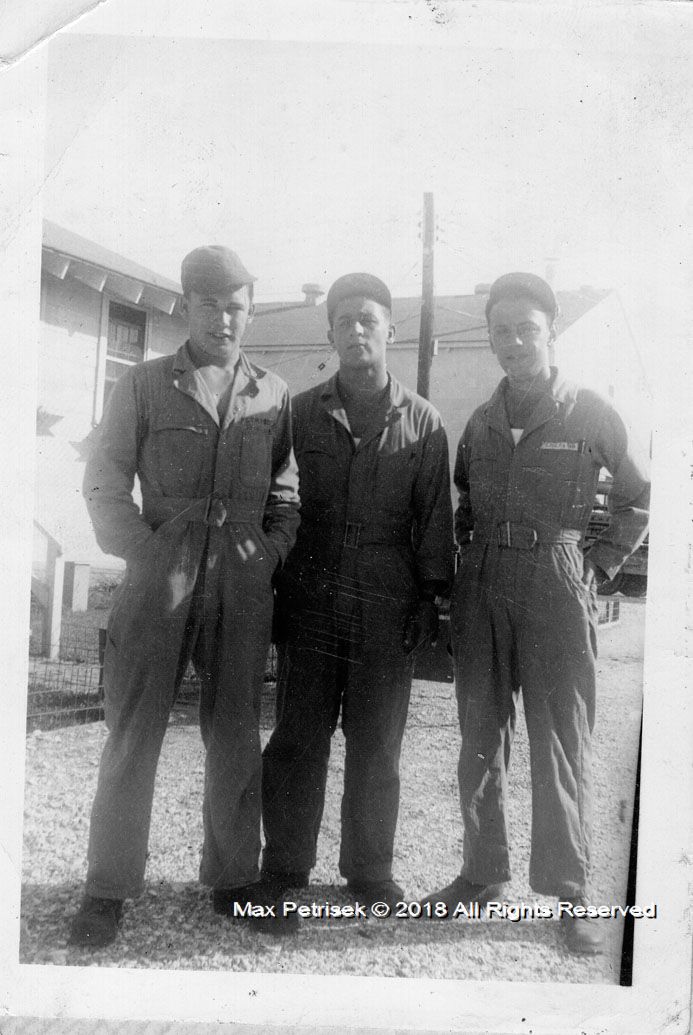

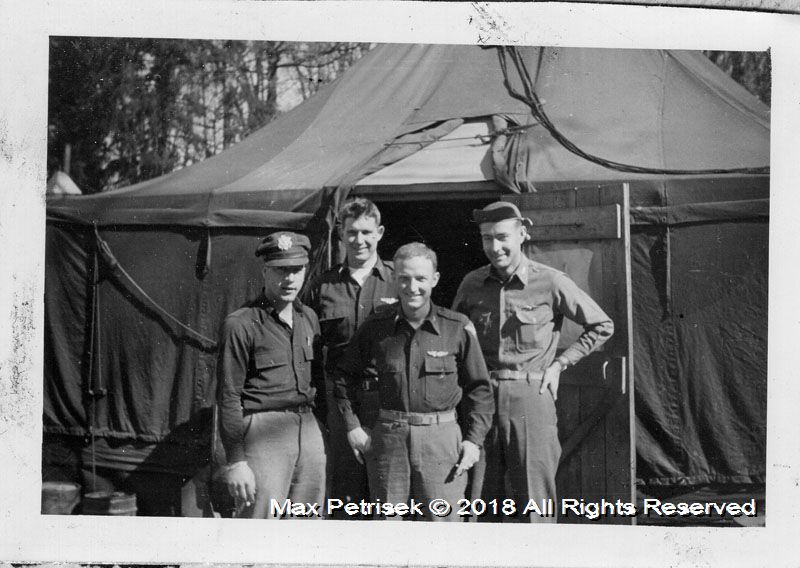

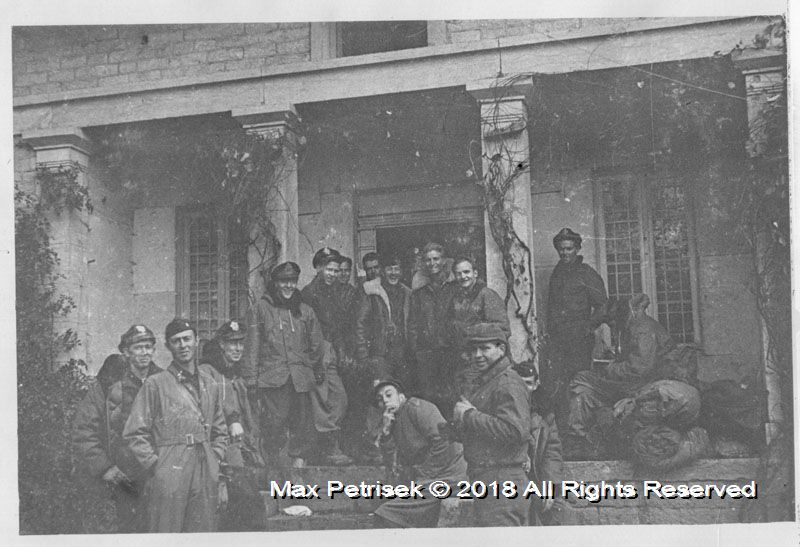

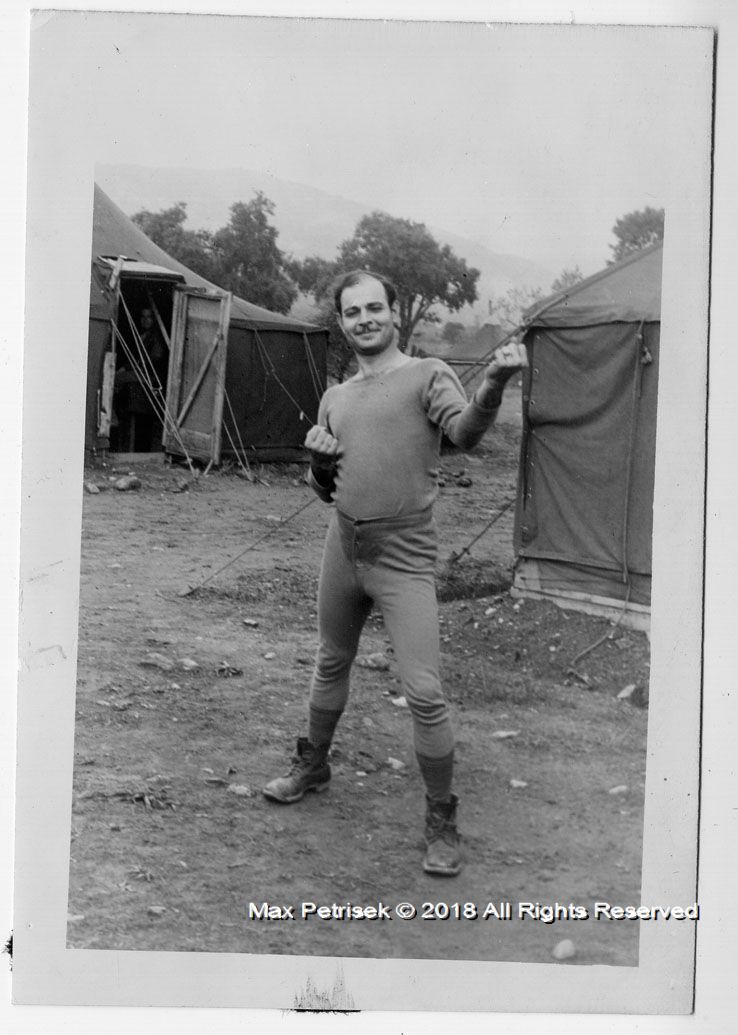

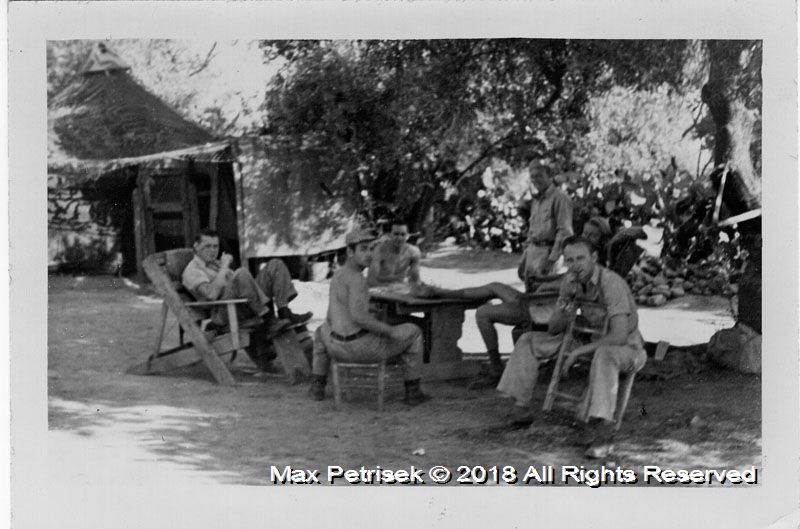

Yes, I did my job as did twelve million other American servicemen and

women in WWII. My survival of combat was only possible because of the

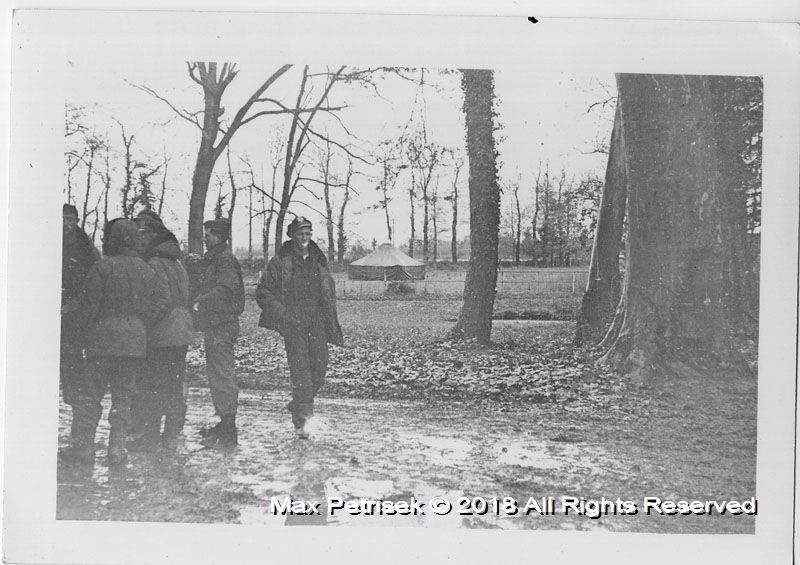

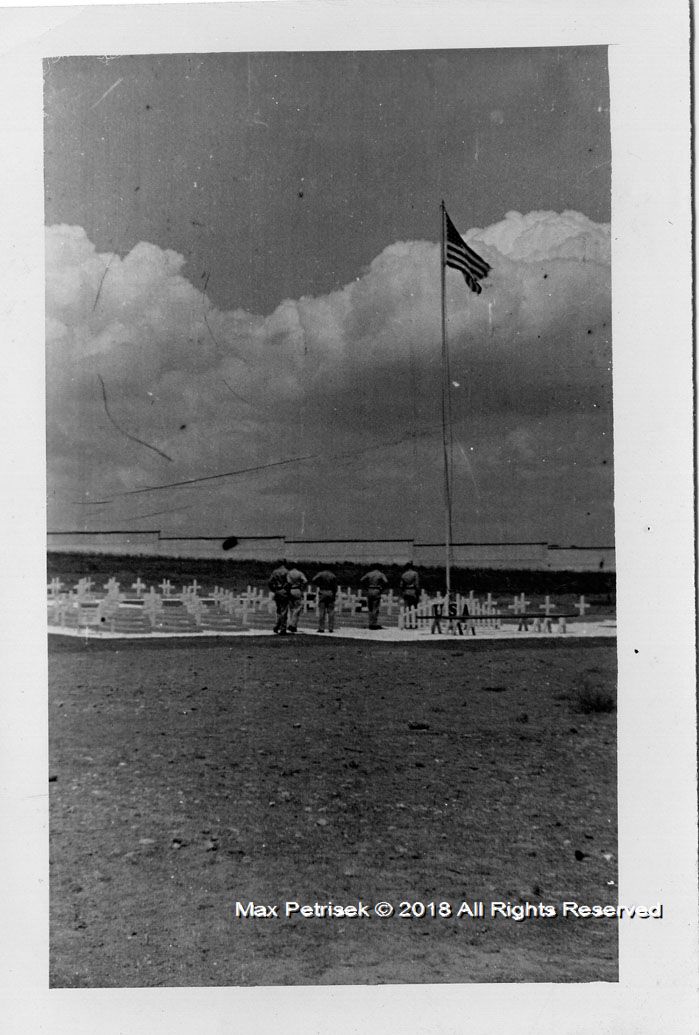

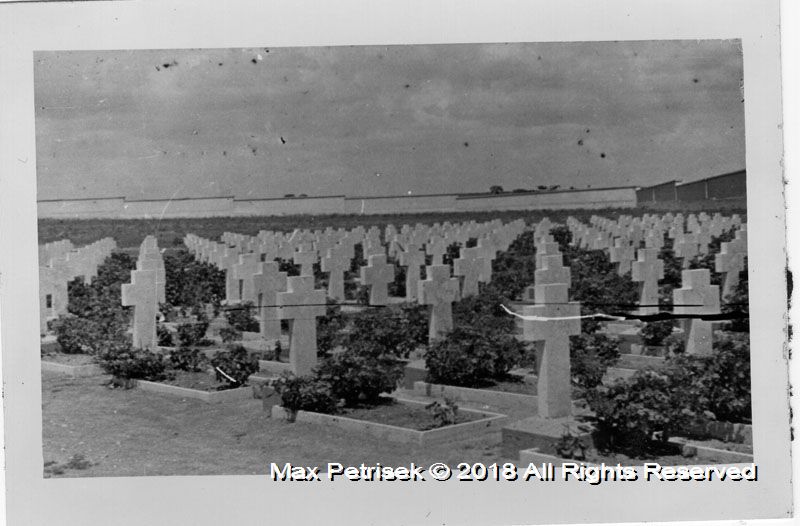

commitment to duty of all who served with me. For several years after the

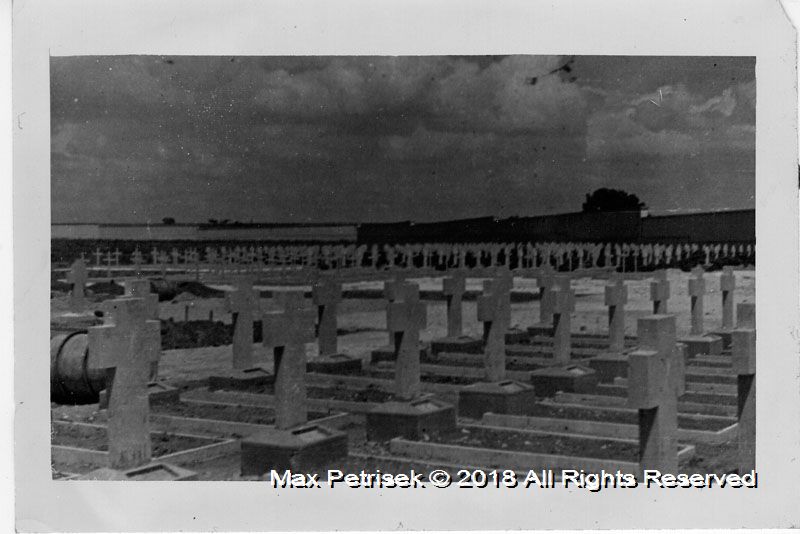

war ended, there was a healing period of visitation to lost buddies'

families, letter writing and funeral services for fallen comrades, and

mostly silence regarding my war experiences. This withdrawal from war

experience was not difficult, as I knew we did a great job, we gave it our

all. We supported our buddies and got one hundred percent support without

asking or pulling rank.

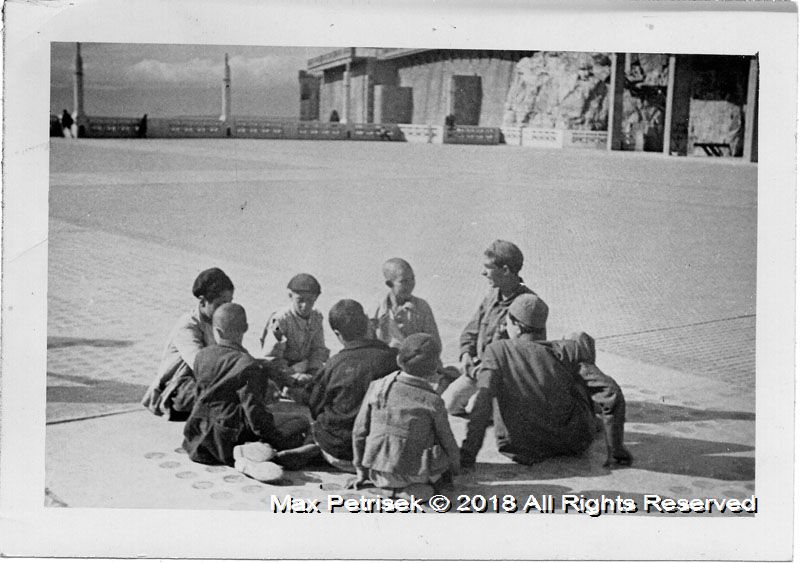

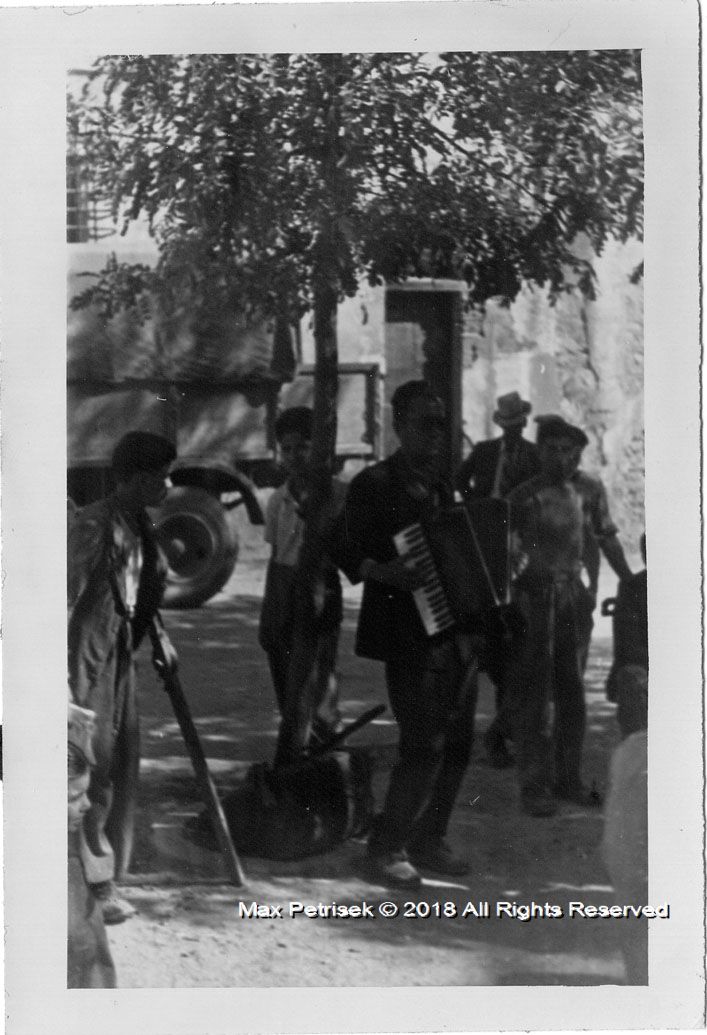

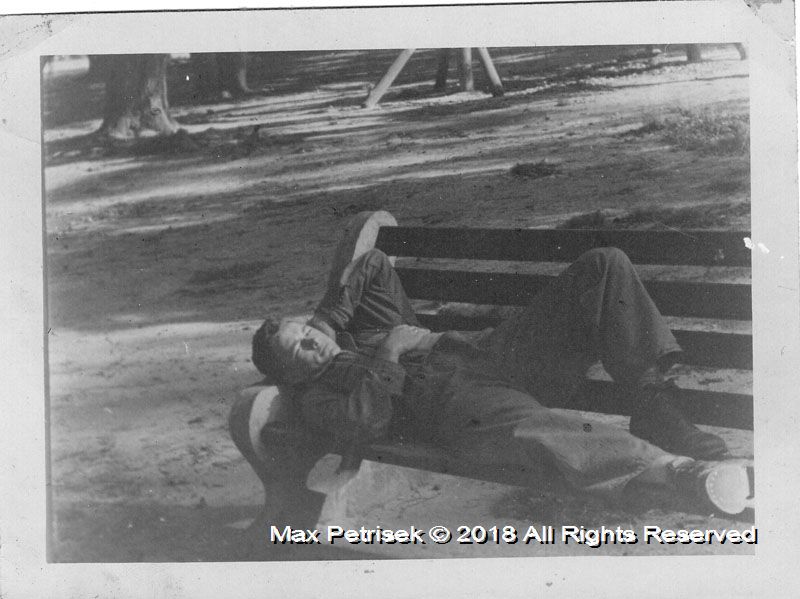

The happiness of returning home allowed the refreshing air of peace and

joy to subdue the war memories. Yes, I saw the eyes of German fighter

pilots barreling through our bomber formation and felt the pain of holding

a dying comrade in my arms. I did lose sleep for a few nights, over such

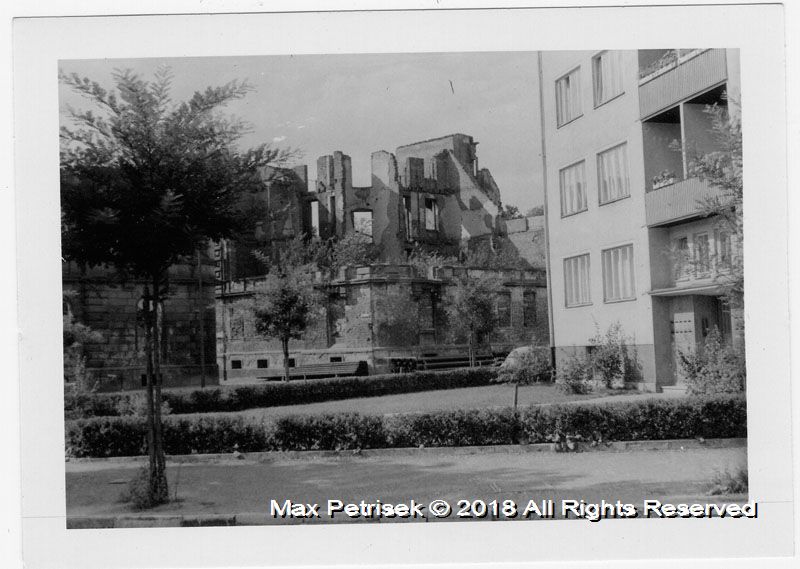

traumatic experiences of seeing the eyes of death. I saw the crews of

German anti-aircraft artillery only a few thousand feet below. They were

firing at our crippled planes as we searched for an emergency landing

field. The fact that the enemy snuffed out the lives of three of the six

original crew, will be forever, like an albatross in my life. This same

feeling of needless loss of life is similar to the loss of my brothers,

Bill and Adam, in the bowels of the coal mines. I do not believe that I

could, or even wish to, ever achieve full closure from these losses. From

an intense, sensitive young eager-beaver, I have developed a sense of

gratification to recall the pleasant memories of knowing such wonderful

people. I am unable to give full and proper recognition to them and the

pleasure of having been a part of their unjustly shortened life.

I have strong opinions, but no comments about the complex circumstances

leading to WWII, or the virtues of any “necessary” war. In my fantasy, I

would wish for a better world or let the evil leaders settle matters in a

personal duel. My wish is that my family, friends and others might better

understand me and my small involvements in the greatest war of all times.

My story is likely to have been influenced from viewing war documentaries

on television. A young family member asked, “Were you frightened while on

a mission?” Without hesitation, I answered, “NEVER!” Then I truthfully

added, “I was never afraid, but I was concerned... I didn't panic.”

All acknowledgement that the United States was helped in winning the war

through the great forces of manpower, equipment and money, this does not

diminish the credit to those who served, but it is to give credit to those

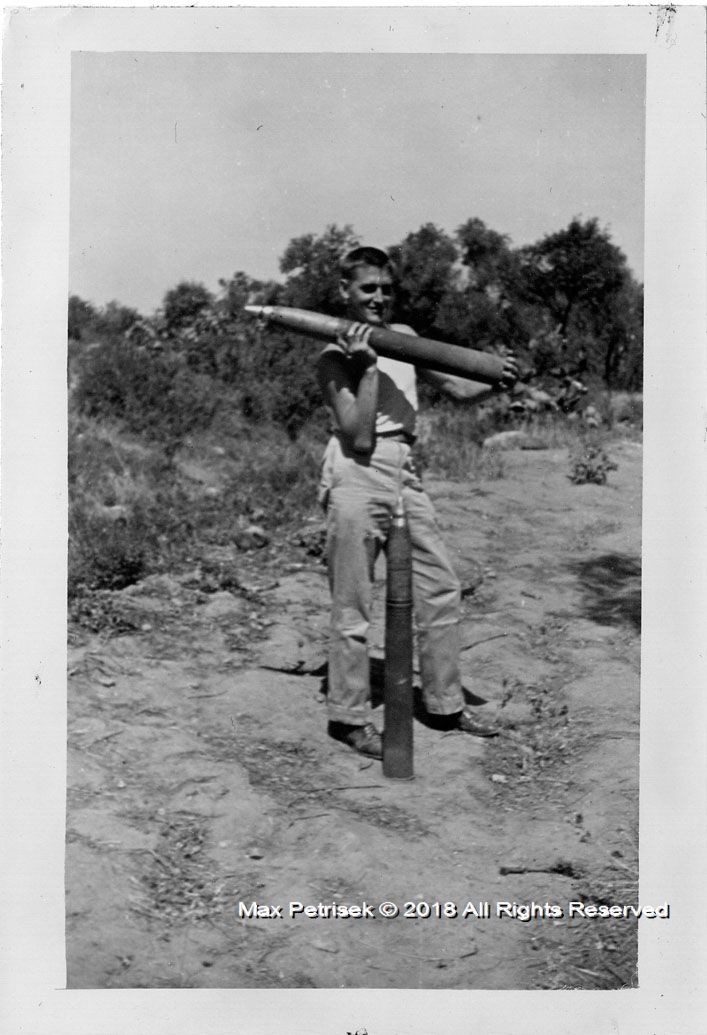

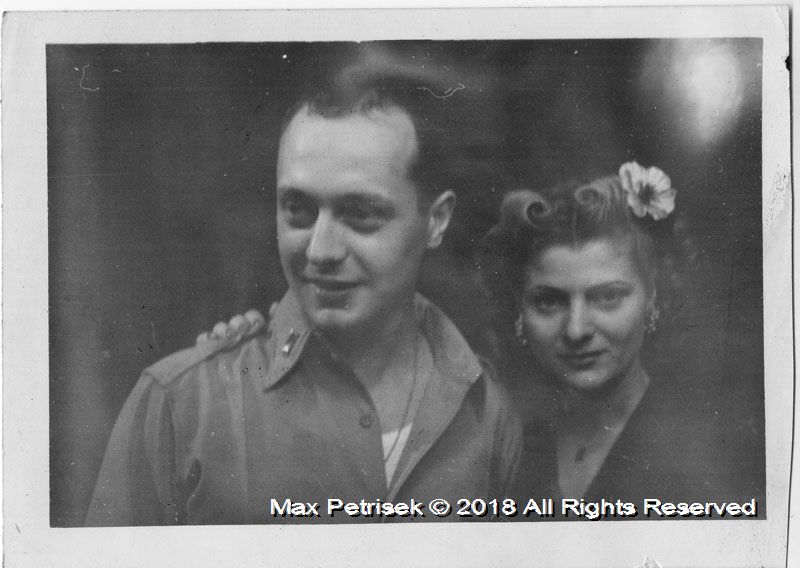

who stayed home and waited and served in the wartime endeavors. My wife,

Marge, was an inspector in a parachute manufacturing plant and also worked

in an artillery shell plant. We, who left home were trained to kill or be

killed. The fact that our enemies provoked the first acts of military

aggression gave me the determination I needed to becoming a warrior.

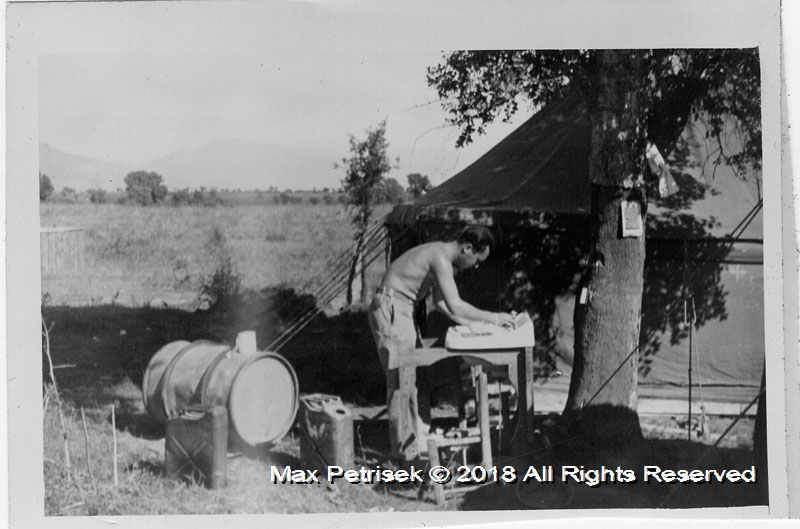

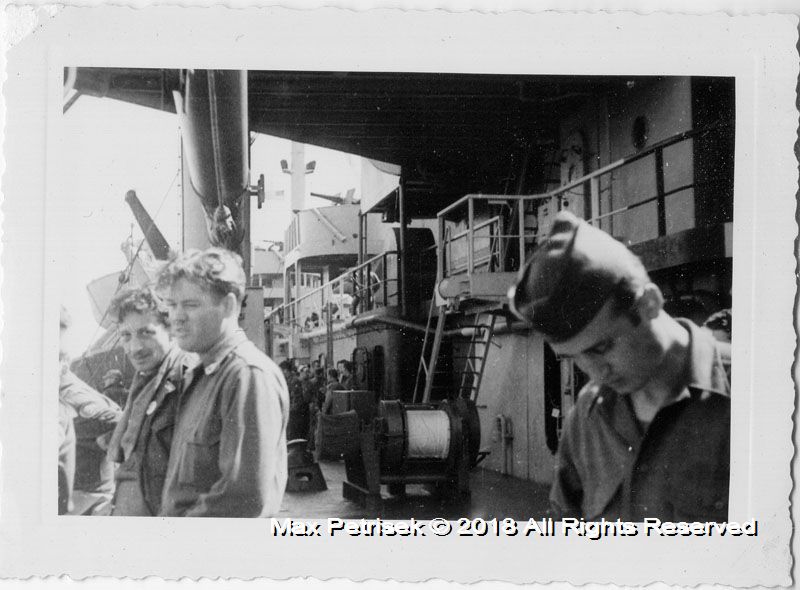

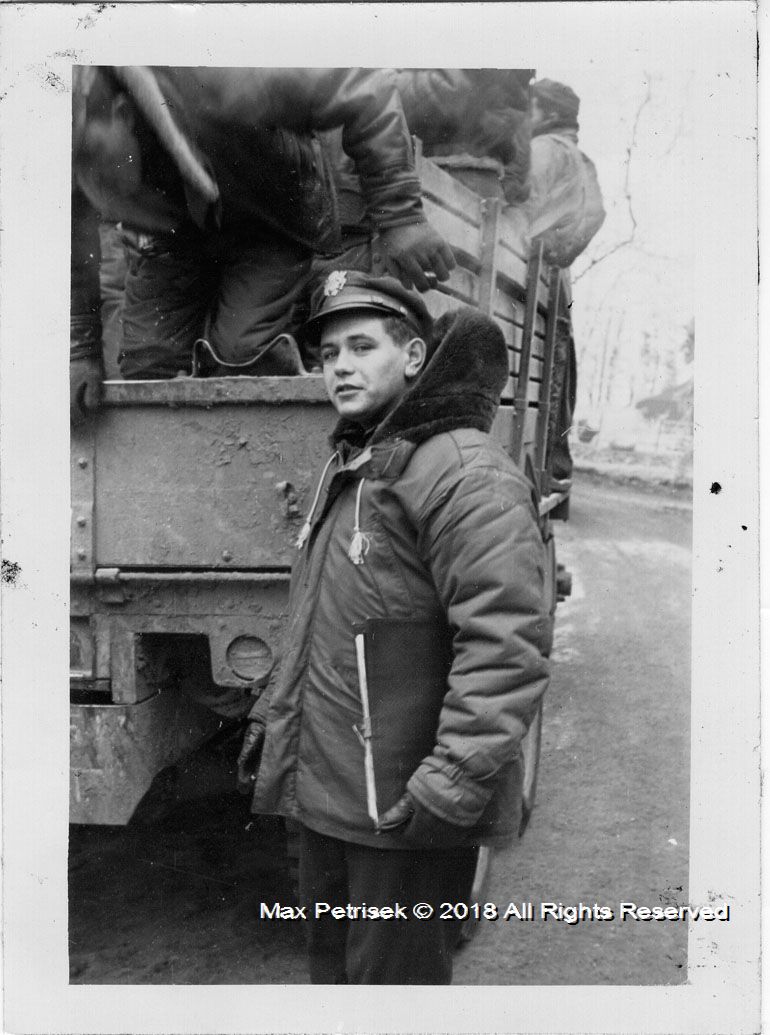

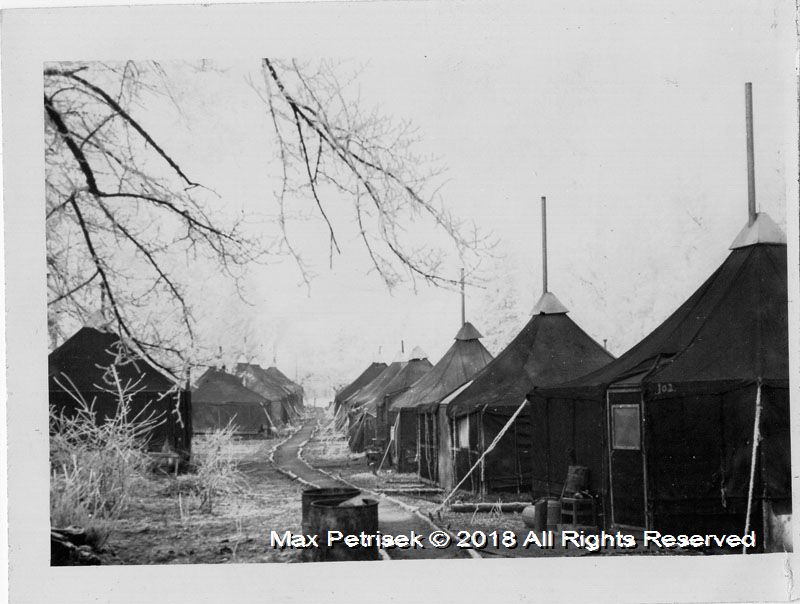

The emotions or sufferings of combat are not the brief encounters with

death. The preparation and involvement “for the duration” was a three year

plus three months of rigorous assignments to disciplined military life

with fifteen months of overseas duty. It was agonizing not to know how

long the war would last or when you would make your last combat mission. I

would have reservations of encouraging any youngster from volunteering as

I had. I was deeply concerned when my oldest son, Ray, joined the Navy for

four years during the Vietnam War. Yes, hearing President Roosevelt give

his famous speech of Pearl Harbor attack will live in infamy, turned me on

to serve. If I had to do it over again, I likely would have given it more

thought. My aspiration is, to never have my offspring go off to war.

Writing my memoirs is a “mission accomplished.”

Max Petrisek |