|

|

Guest Book | Pages & Links |

Lloyd E. “Dabney” Kisner

323rd Bomb Group, 455th Bomb Squadron

DURBIN — Lloyd "Dabney" Kisner of Durbin is best known in his town as an avid outdoorsman, with stories to tell about the bear that attacked his beehives or the fish that almost got away. But his experiences as a bombardier-navigator in World War II and his many close brushes with death make a story that beats them all.

On Sept. 11, 2001, the day the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were attacked, a Belgian government official signed certificates on behalf of his people honoring Kisner and other American veterans for helping to liberate their country nearly 60 years earlier.

The framed Belgian certificate, and two small Caterpillar Association buttons recognizing Kisner for escaping from a damaged plane in a parachute, are on display in his backcountry trailer home in Durbin, Pocahontas County.

On Dec. 13, 1943, four B-26 Marauder bomber groups dispatched 216 aircraft in a series of flying formations over Holland to deliver 400 tons of bombs on a key Luftwaffe facility, the Amsterdam-Shipol airdrome. The 323rd Bombardment Group was on its 13th bombing mission, and Lt. Kisner was camped out in the nose of the plane as it flew straight into a large, black cloud of an anti-aircraft barrage. The exploding flak penetrated the plane, hit Kisner in the face and stomach and knocked out one of the planes’ engines.

Thanks to his bulletproof flak suit, Plexiglas safety glasses and a plucky pilot who flew the damaged plane to safety, Kisner survived to tell the tale.

As the crippled plane burned, the crew dropped its bombs. Then the pilot turned around and flew it back over the North Sea toward England, where Kisner and the rest of the crew bailed out in parachutes. Kisner landed in the middle of a minefield, where he remained unconscious and unaware of the danger while British mine experts helped an ambulance crew safely reach him and take him to the hospital.

Ten days later and just discharged, Kisner was back up and flying another mission. It was a massive Allied attempt to knock out the Germans’ newly tested big gun at Calais, France. The airborne fight was intense. Kisner remembers watching helplessly as the plane next to him was struck and plunged toward the ground.

"When you looked out and saw the airplane going down and there wasn’t any parachutes-well we called that ‘buying the farm,’" he said. Whenever a soldier was killed in action, he explained, the government gave their families $10,000 — about enough to buy a farm in those days.

The bombing runs had by now become terrifying, and some airmen refused to go on any more runs, he said. A few times, Kisner flew in the place of a young "boy" who was scared. One day, a plane he was thought to have been on was shot down. His parents in Elkins received a false "missing in action" telegram for the second time before the truth was sorted out.

"I was scared all the time. If you weren’t drinking, you were scared," Kisner said, and plenty of drinking and bar fights took place every night after a bad bombing mission.

On May 25, 1944, Kisner again escaped from a burning plane by parachute near Leige, Belgium. The B-26 he was aboard, the Dragon Wagon, was on its 57th bombing mission when it was hit by German flak. Both engines were knocked out and the plane was ripped to pieces when the crew bailed out, Kisner said.

As he drifted over small country villages, Kisner watched the people below, pointing upward and following on their bicycles the parachuting airmen. (The rest of his crew was caught and taken to a German prisoner of war camp, where, Kisner later discovered, they remained for the duration of the war.)

Kisner landed in the middle of a street. He said some of the hundreds of Belgians who watched his descent ran to his parachute and started fighting over it. But a few helpful villagers pointed toward a field on the edge of town where he could escape. As the frightened American flier approached a fence around the town, a pretty girl grabbed and kissed him, leaving a lipstick smear that he later thought was blood. Kisner said he climbed the fence and ran through the high wheat until he found an abandoned mine where he could safely hide, pointed out to him by sympathetic farmers. Some children soon found him in the darkness and fed him bread and drink. He waited there until the Belgian underground arrived.

Kisner was later moved to a barn to hide, along with another rescued American flier, an engineer named Andy Marcin from a downed B-17 Flying Fortress. They were given new clothes, new identities and fake work documents. If asked, they were to be Flemish coal miners.

The two GIs were hidden for almost a month in the home of "Mr. and Mrs. Barbe," who risked their lives and those of their two children for doing so.

Meanwhile, atrocities occurred all around them, according to Kisner.

One day, as German occupiers loaded a large group of Belgian prisoners into a truck to be taken to a prison work camp, a girl suddenly knelt in the middle of the street to pray. A Gestapo soldier took the butt of his rifle and bashed in her head. They left the girl lying there dead in the street, Kisner said. That day, friends in the Belgian underground held a prayer service in her honor in the Barbes’ home.

Another time, the Americans were sent up into the attic to hide as German soldiers filled the streets below. As they listened to the din and wondered, German soldiers broke into the home of a nearby Belgian family, whose father had with ties to the underground, and shot the children. The mother jumped out of an upper window to her death, with a baby in her arms, Kisner said. Another prayer service took place at the Barbes’ house.

The atrocities greatly scared the Barbes. Soon thereafter, the American GIs were moved to another safe house.

They were taken on a bus headed to an area closer to Germany. The underground felt a trip in that direction would be safer for the Americans, who would not be suspected as escapees. Nazi soldiers, returning home, packed the seats and the aisles. One badgered Kisner, sticking his gun muzzle into the frightened American’s nose, and trying to get him to stand up. Amazingly, "Chief", an underground leader accompanying the escapees, got the German to back off.

The American soldiers were hidden in a restaurant basement until a new safe house could be found.

One day, Kisner was given a cow to drive, and the two airmen drove it to a nearby slaughterhouse, straight under the noses of two German guards. The slaughterhouse, meat market and adjoining farmhouse would be their hideout for several months. The farmhouse belonged to Louis Fechir, who had a wife and three children, and needed the kind of extra help that only Kisner, a rural West Virginian, could provide. Kisner said he became the "main gear" in the slaughtering and butchering operation, but steered clear of places where he could be seen.

"I lived in that house three months and never saw the front of it ‘til I rode up in a tank," he said.

When not working in the slaughterhouse, the airmen hid up in the attic, But at night, the Fechirs closed their shutters and let the GIs come down to eat dinner and socialize with the family. Kisner said a particularly bright spot in his life was getting to know a pretty and fiery underground activist named Marguerite "Mimi" Brixko, who lived next door. Brixko played cards and entertained the GIs with stories, and taught Kisner to speak French.

One day a local villager tipped off the Germans that someone was hiding in the Fechir house. Before the German soldiers arrived, Brixko took Kisner to her own house next door and hid him in a small closet under the stairs. Kisner remembers his heart beating loudly as the soldiers opened doors and closets, searching the house and walking up the stairs, right over him.

Another time, men broke into the Fechir house and stole things. Kisner thought the burglars were German soldiers, so he ran downstairs, through the meat market, slaughterhouse and barn, finally hiding in the doghouse, until the danger had passed.

One night as German planes flew overhead, the underground recruited Kisner to signal to an American plane using Morse code and lights from the middle of a dark field. The plane mysteriously arrived, dropping off men, radios, guns, ammunition and other badly needed supplies to the Belgian underground.

But what happened next is difficult for Kisner to recount. He still chokes up upon telling it. Rather than taking him back home, the underground took him along to watch them execute two Belgians who had squealed on some of the underground rescuers. The bloody sight of the men, shot dead in holes they had dug, haunted Kisner, causing more than a few sleepless days and nights.

The last time the German soldiers came searching for hidden Americans, Kisner was taken to a bakery, about 6 miles away, where he stayed and worked, baking in the kitchen until American forces finally arrived on Sept. 11, 1944.

The older he becomes, the more the 82-year-old Kisner wonders why the Belgians would risk their lives to save others. He has never asked his rescuers, but Kisner said he thinks he knows why. Not only did they like and admire the Americans, who they hoped would one day rescue them, but they despised the German occupiers, who didn’t think twice about killing citizens and innocent children, he said. Hiding an American was a good way of fighting back, Kisner said.

Unlike the other Americans in hiding, Kisner also believes that his rural Pocahontas County background came in handy. It helped him to become useful to rescuers living in rural farming areas of Belgium. It also helped him remain anonymous and, ultimately, to survive.

After the death of his wife, Kisner learned of Mimi Brixko’s address in Belgium, and they have been writing lengthy letters to one another ever since.

Last month, on her 80th birthday, Kisner phoned Brixko and spoke with her for the first time since the war. Communication, in halting French and English mixed with tears, was difficult, he said. But being remembered and thanked obviously meant a lot to Brixko, according to Kisner. He said it also means a lot to him.

Heidi Zemach is a contributing writer to The Pocahontas Times

‘Dabney’, Lloyd Edgar Kisner, Jr., age 100 and a lifelong restaurateur, hunter,

fisherman, centurian, and Uncle passed away on a snowy morning, December 1, 2020

at Davis Memorial Hospital in Elkins, WV from declining health. For the past 2

years, Dabney was a resident of Colonial Place in Elkins, WV, but he spent the

majority of his life in Pocahontas County in Durbin and Frank, WV. Dabney was

born on January 13, 1920 in Frank, WV, son of Lloyd Edgar Kisner, Sr. and Edna

Graham Kisner.

As a teenager, Dabney helped his father build Kisner’s Store Building where the

family lived upstairs and ran the general store downstairs. He graduated from

Green Bank High School where he played football.

In 1942, he entered Army Boot Camp and in 1943 received his “Wings” from flight

school in Texas. In 1943 he flew his first mission from Earls Colne, England as

a bombardier/navigator. After this mission he also was a co-pilot in a 5-man

crew. On December 13, 1943 Dabney was shot down over Europe but it made it back

to White Cliffs where the crew parachuted out. He landed in a minefield but US

soldiers carried him on a stretcher unconscious to the hospital. On Dec. 24 he

was released and on Christmas Day 1943 he flew another mission and then 48 more.

On May 25, 1944 Dragon Wagon B-26 was shot down over Liege, Belgium. He was

rescued by the Belgium Resistance and hidden in several locations over the next

5 months. He worked with the Belgium Resistance as he helped them identify the

US airplanes or enemy planes at night by the sounds of the motors. He was often

hidden behind a closet door or in an attic.

On September 7,1944, Liege, Belgium was liberated. Dabney rode on a USA tank

through town and finally saw the front of the house where he had been hidden in

the attic. He was ordered to go to Paris for debriefing then returned to

England.

Dabney was sent home on leave and he told the Statue of Liberty that she would

never see him again. He never flew again. He reported back to the Base for

training on the Norton System, but chose to come home with his Honorable

Discharge as a Lieutenant. He was awarded two Purple Hearts, a Distinguished

Service Cross, the Air Medal for heroic action while participating in aerial

flight, two Caterpillar Pins, and a Special Award from Belgium Red Cross.

On March 6, 1947 he married Irene Jones of Elkins, WV on her birthday. They were

married for 52 years. Dabney and Reeny were part owners of the Bartow Drive-Inn

but sold their share when they opened the Pocahontas Motel and Restaurant in

1953 at the top of Cheat Mountain, which they operated until the 1990’s. The

restaurant was famous for the German pot roast and homemade pies. Reeny passed

away in May of 1999.

Dabney hosted hunting groups including deer, raccoon, and bear hunters. He also

raised hunting dogs for coon hunting. He was an avid fisherman and taught all

his nieces and nephews how to fish. He spent hours making intricate fishing

flies. Dabney and Reeny moved to Olive, their mountain farm, when they retired.

On this gentle farm, Dabney grew Christmas trees, raised peacocks, and cared for

his horses. Dabney believed in protecting the environment and preserving

wildlife before it was fashionable.

In 2011, Dabney bought a home in Frank across the road from his family’s store.

In 2018, he moved into assisted living at Colonial Place in Elkins, WV. On

January 13, 2020 his family celebrated his 100th birthday with a party that

honored his interesting life and adventures.

Dabney was a member of the Elks Club, the American Legion, the VFW and the

Durbin United Methodist Church.

Dabney was the last surviving member of his immediate family and was preceded in

death by his parents, his sisters Marguerite (Peg) Widney, Geraldine (Gerry)

Lawton, Pauline (Polly) Mams and his brother William (Bill) Kisner. Also,

preceding him were his in-laws Dr. Franklin Widney, Bruce Eugene Lawton and

Joseph E. Mams.

Surviving are sisters-in-law, Edith Kisner and Carol Erickson. Nieces and

Nephews include Rebecca and Fred Benton, Marsha and Don Wehr, Sarah and Joe

Burch, Jay and Doreen Widney, Kevin Widney, John Lawton, Barbie Stewart, Kathryn

Herbert, Cathy and Jeff Orndorff, Franny and Karl King, Frank and Robin Mams,

Barbie and Ronnie Pugh, Ed Calain and others on the Jones side of the family as

well as many great and great-great nieces and nephews. Dabney also had special

friends including Dave and Martha Burner.

The family is grateful for the excellent care that Dabney received at Colonial

Place and the Davis Memorial Hospital.

Dabney and Reeny had a special place in their hearts for the Emergency Squad as

they helped seed money to establish it. Contributions can be made to Bartow

Frank Durbin Volunteer Fire and Rescue Company, PO Box 267, Durbin, WV 26264 at

or Meals on Wheels at Pocahontas County Senior Center, Inc. PO 89 US Rt. 219

North, Marlinton, West Virginia 24954.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic a small graveside service was held and a larger

memorial service with military honors will be scheduled this summer.

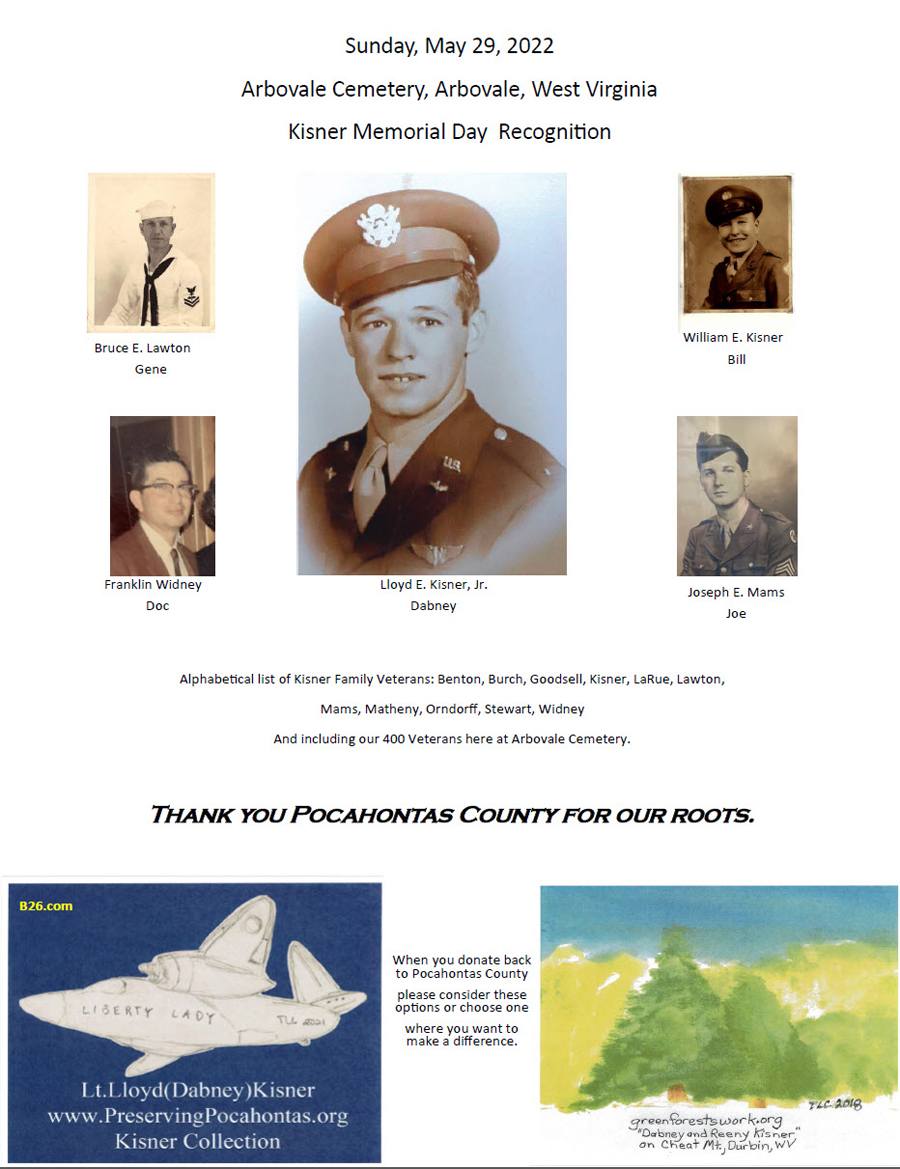

On Sunday, May 29, 2022 a Memorial Day service and military ceremony was held in

Arbovale, WV.

The following is quoted from THE POCAHONTAS TIMES NEWSPAPER article written by

Suzanne Stewart and photograph by Suzanne Stewart. Retired Marine Capt. Rick

Wooddell is commander of the Pocahontas Veterans Honor Corps.

Wooddell added that he wanted to make a special tribute to Pocahontas County’s

own Dabney Kisner who passed away at the age of 100 on December 1, 2020. We

would like to honor World War II USAAC veteran Lt. Lloyd E. Kisner, Jr. (Dabney)

who is best remembered for having to bail out of two damaged aircraft and was

protected by Belgium citizens until he could be repatriated. Wooddell said. Let

us honor all our heroes who are no longer with us. Let us strive to live up to

these examples of selfless patriotism.

The ceremony was concluded with a 21-gun salute and Taps.