|

My son, John W. Eubank III, requested information of my military career

in June 1996 and here is a brief summary. It took two years, leisurely, to

gather the material with much help from Jack Kelly, Guy Ziegler and Warner

Hutchinson.

September 24, 1942 I was inducted into the Army - FORT LEE, PETERSBURG,

VIRGINIA. I stayed there for a week - issued uniform, received shots,

received instructions and was humiliated as all G.I.s were.

September, 1942 - Departed from Fort Lee to ATLANTIC CITY, N.J. I was

stationed in the PRESIDENT HOTEL on the Boardwalk, 4 G.I.s to a room.

Wonderful accommodations and good food - except for Waldorf salad. They

served that at every meal - I had never eaten Waldorf salad before. Anyway, I

developed a huge dislike for Waldorf salad and when I got out of the service I

didn't eat any for over 25 years. I received my basic training and took

all kinds of aptitude tests at Atlantic City to determine what G.I. Buddy

should do for the W.W.II effort.

I loved Basic Training even though the D.I.s (drill instructors) tried to

act tough to discipline us 'yard birds'. I learned all the moves fast and

led some of the groups. It was a great deal of fun marching on the

boardwalk. A.C.s season was similar to Virginia Beach - Labor Day to

Memorial Day - so the beach was not too crowded. However, many bathing

beauties enjoyed watching us - hut-two-three-four- up and down the

boardwalk all day. One of them, beautiful petite, Lois Anderson, fell in

love with G.I. Buddy and cried when I left A.C.

Charlie Wood, a room-mate from Clifton Forge, Va. could not learn how to

march. He was a farmer and he couldn't learn to left-face, right face,

about face, to-the-rear march, etc. I can hear the D.I. now: "YARD BIRD",

he screamed, "WHEN I SAY LEFT FACE, I MEAN LEFT FACE" and so on. The rest

of us would go marching down the board-walk and the D.I. held Charlie back

alone yelling at him trying to get him to do "left face", "right face",

etc. It was very sad - Charlie could not learn - and one afternoon when I

came back to the

room - Charlie was there packing - they were sending him to cooking

school. It was rumored then that soldiers too dumb to learn things were

sent to cooking school. It's a pity. Charlie was extremely handsome, about

6'4", humped over from years of following a plow and never been out of

Clifton Forge, Va.

The aptitude tests said I should go into radio - a four hour test of

sounds in an ear phone I was wearing ie does dit-dit-dit-da-dit da da da

dit dada da sound more like dit-dit-da-dit-dit-da-da dit dit di dit-da or

like da-dit-da-da-dit-da-dit-dit-dit-da-dit da or like

dit-dit-dit-da-da-dit-da-dit-dit-da-da-dit--I got a good score on

this--maybe because I survived the 4 hour ordeal. But Abie Humelberg, a

Boston cab driver fell asleep during the test and he got a good

score-better than mine...

So off goes G.I. "Abie" and G.I. Buddy and others off to radio school in

November, 1942 to Truax Field in Madison, Wisconsin. Of course thousands

of other G.I.s were headed there also from all over the country. We

arrived in Madison (on a train) at about 2:30 a.m. It was late November

and it was raining cats and dogs and the temperature was in the low

30s..... we still were wearing khaki uniforms. As we got off the train,

the first thing we heard was: "Line up at attention"---We stood at

attention on the platform of the station for at least an hour. We got

soaking wet and were freezing ---Abie Humelberg fell asleep at attention.

We were at Madison, Wisconsin for sixty plus days. We went to school in

shifts as it was rush to get the soldiers trained. I guess the graveyard

shift was the toughest---12 midnight to 8 a.m. We would march to school in

250 below zero weather----your nostrils would ice up and frost on your

coat collar. I estimate there were 20,000 soldiers at Truax Field at a

time, all being taught how to maintain radios.

You probably guessed it--Abie Humelberg slept through most of the classes.

He flunked out and I think he was sent home. He was much older than the

rest of us and he had a lame leg and walked with a limp. I really don't

know how he passed the physical and got in the army. We became good

friends.

After finishing Radio School some of the guys joined outfits all over the

country.

A few of us who did well at Truax were sent to Radar School in Boca Raton,

Florida. Man, that was a pleasure leaving the freezing weather in

Wisconsin and arriving to 800 weather at Boca. At Truax we lived in

barracks with about 50 men in each. Showers and latrines were in a

separate building behind the barracks. At Truax the barracks were heated

by three pot-belly stoves. If your bunk was close to a stove you burnt up

and if too far away - it was very cold.

However, at Boca you didn't have a stove and air condition was unheard of

for the soldiers. In addition to radar school we received combat training

with guns, gas masks and everybody had to learn how to swim. There was

very little to do at Boca Raton -- Florida was undeveloped at that time.

Nothing much in Boca except one big Hotel Resort and hardly anything in

Fort Lauderdale.

One thing I vividly remember at Boca is this: There was a tough mess

sergeant and after each meal you (if on K.P.) would have to move all the

tables-benches (attached) out-of the mess hall. The mess hall was a big

open building with 2"-10" wooden floors. The mess sergeant would cut up

G.I. soap all over the floor and crush it into the wood floor with his

boots and the K.P. guys would have to scrub all the soap out of the wood

floor with a brush on your knees. Needless to say-- he had the cleanest

mess hall in the army. No ants or roaches and the wood was blanched white

from the scrubbing.

From Boca I was assigned to 394th Bomb Group in the 585th Squadron at

MacDill Field in Tampa, Florida. I would remain in Communications and with

the 585th Squadron of the 394th Bomb Group until the war was over.

At MacDill we lived in tents pitched over sand ... eight of us to a tent.

It was July 1943 and the temperature in the tent must have been 110

degrees in

the daytime. And at night the mosquitoes as big as horseflies came

out--wow! This was the most difficult duty that I experienced. It was

almost unbearable ... each day seemed like a week.. not only the

mosquitoes but there were sand fleas that were hungry during the day.

This was the first time we dealt with planes. It was a Martin B-26 and it

was nick named "the Flying Prostitute" because it was difficult to handle.

It had two big R-4800 engines to propel it over enemy territory and back

again at 300 miles an hour --- after dropping 4,000 pounds of bombs. For

defense against enemy fighters she had two fifty caliber machine guns in

the tail, two in the dorsal turret, two in the waist, two in the nose and

four fixed package guns along the side of the fuselage. The Lady was

equipped to take care of herself.

There was only one thing wrong with the dream girl--she was hard to

handle. The reason was she had stubby, cherub-like wings carrying 35,000

pounds of airplane. The Lady had to run like heck down the runway to get

off the ground. She would take off and land at 145 miles an hour. "She had

a lot of tricks." If one of her 2,000 horse-power engines missed a few

beats on the take off, it was too bad. The Lady did a disastrous side flip.

But once in the air, the Lady regained her equilibrium. She began to get a

shady reputation. Pilots began to groan about her. They christened her

"The Flying Prostitute" because of her cherub wings. They said that she

had no visible means of support --- There were rumors that the Lady was a

tramp and might be barred.

Yes, the B-26 Marauders were hot babies -- very temperamental and had to

be handled like a spoiled kid. The residents of Tampa knew she was hot

stuff -- they had an expression: "A plane a day in Tampa Bay". Some pilots

called her the "Flying Coffin" and suggested ornamenting the fuselage with

silver handles.

The young pilots were audacious and obstinate, too -- they flew the plane

until she was sk9broken. It took guts and nerves but they did it.

Then we continued our training in ARDMORE, OKLAHOMA, the "Land of the

Indians" The airfield was next to Gene Autry's Flying A Ranch and his

ranch was "off limits" to G.I.s. Boy! it got hot -- even hotter than

MacDill -- one day the mercury rose to 1200 on the runways. But

surprisingly there were no mosquitoes or other bothersome insects. The

planes practiced simulated training missions with practice bombs.

We left Ardmore the latter part of August 1943 for Kellogg Field in

Battlecreek, Michigan. At this time the Group had grown to 219 officers,

1,118 enlisted men and 31 aircraft. On one of the practice missions a

"flour sack" bomb fell on the rear end of a military police captain as he

was bending over. He didn't think it very funny. Around September 9th we

were moved to Atterbury Army Air Field, Columbus, Indiana for maneuvers.

To simulate combat conditions as closely as possible the planes flew

strafing runs on tanks, ground troops and blowing up bridges. The raids

were carried out as close to actuality as safety would permit.

When I went into the Army I weighed 140 pounds at 6'2" -- On October 15

when we left Atterbury to go back to Kellogg Field I weighed 175 pounds.

During the maneuvers at Atterbury the mess hall was opened 24 hours. Most

every night I would go in for a midnight snack. I would eat 10-12 eggs,

several big fresh sliced tomatoes, ham, bacon, 7-8 slices of bread. The

mess sergeant would fix you anything you wanted and it was the first time

in my life I had all I wanted to eat -- That made up for the hard work

during the maneuvers. More training for overseas during October, November

and on November 27 we received the long-awaited warning orders for going

overseas. However, we did not depart from Kellogg Field until February 15,

1944. The planes had left in December.

It took six trains to transport the ground echelon the 900 miles from

Kellogg Field to Camp Miles Standish, Taunton, Mass. This time was spent

attending lectures, films and obtaining any shortage of equipment needed

for overseas.

On February 27 we departed Miles Standish for the Boston Port of

Embarkation (30 miles). We boarded U.S. Army Transport, George W. Goethals that evening --- Then G.W.G. sailed for a destination unknown to

us.

The voyage over was calm and uneventful for the men of the 394th

Bombardment Group. We spent time playing cards, walking the deck with an

occasional glimpse or chat with one of the 200 nurses on board.

The ship served meals at 6 a.m. and 6 p.m. so if you missed breakfast or

were sick at sea --- you starved before dinner. There were no snacks or

canteens. A-few guys were so sick they couldn't get out of their bunks for

several days. The bunks started 12" from the floor and every 20" was

another bunk -- Bunk over bunk about eight deep. There was no hot water --

there was no fresh water for a shave or shower. Both were done in cold sea

water. Some of the guys who were sea sick and hungry probably thought they

would rather be dead.

There was a huge armada of ships making up our convoy that had to zig zag

the course to minimize the chance of detection by German Sub-marines.

Finally, on March 8, 1944 at 1315 the troops spotted land and a big roar

went up. Everyone was certain that they didn't want another boat ride soon

unless it was headed back home. The Goethals was now in the Firth of

Clyde, Scotland. Due to a very slow movement of the convoy up the river we

did not disembark until the next morning,

March 9th at Greenock, Scotland. During the entire voyage no submarines or

enemy aircraft attacked; however, it was learned that some submarines did

threaten to intercept the course of the convoy.

After disembarking practically everyone kissed the good earth -- even the

guys that were extremely sea sick felt good again and wanted to get into

the fight against the Germans.

We loaded an awaiting train. We received doughnuts, coffee and goodies

from American Red Cross girls. The train went through Glasgow, Scotland

and all along the way rosy-cheeked children gave us the V for Victory

sign. They would yell at us, "Any gum, chum?" as they had never had gum

before.

After an all night train trip we arrived in Chelmsford, England on March

10, 1944. At the station we were met by the air echelon and escorted to

Boreham Field. The ground and air echelons were glad to be together again.

Now we could get a combined effort towards getting organized and

operational to begin to bomb targets inside Europe. The first combat

mission was on March 23 just 13 days after we were reunited. Gosh!, there

was a great deal of excitement seeing the 36 plane formation leave for a

raid on an airdrome at Beaumont-le-Roger France. All returned safely but

due to a cloud cover the bombs fell long on the target. Three days later

the crews raided a heavily defended boat pen area at Ijmuiden, Holland. 52

planes (maximum effort) from the 394th (585th, 586th, 587th,588th) helped

to kill over 800 German soldiers. The 585th Squadron (my squadron) lost

its first plane in action and four men were killed and several other

planes were damaged by flak.

Luring April '44, 23 missions were flown using 539 sorties and dropping

1,000 tons of bombs to blow the "H" out of Hitler. Three planes came back

with one engine shot out and the planes made belly landings. 28 missions

were flown in May dropping 1500 tons of bombs on railroads, bridges, gun

positions, marshalling yards and troop concentrations throughout France

that the B-26s could reach. May was a good month; the group lost only one

plane. That was a 585th crew and all six men were seen parachuting to the

ground. Intelligence reports confirmed that two crew members were picked

up by the Free French, three became P.O.W.s and one missing in action. One

of them, Bill Edge, friend of mine that was picked up returned to duty and

when we arrived in France around August 25th Bill surprised us by coming

to our air strip.

On the night of June 5, 1944, there was a lot of excitement and

anticipation by everyone. We were sure something big was about to happen.

No one had said anything to us or even hinted anything but there was much

tension in the air. We were awakened at 6 a.m. on June 6th and told the

news of D-Day and the Battle for Normandy. The

394th made two missions over Normandy that day, one in the morning,

another in the evening. The crew members told us: "There were hundreds of

planes -- all a part of the Allies great air forces. Upon reaching the

English Channel they could see boats thick enough to almost make it

possible to walk all the way across the Channel". The 394th lost

four planes -- some mid air collisions due to poor visibility.

During June and July the 394th flew 39 missions using 2,249 planes and

dropped 2,200 tons of bombs on bridges, fuel depots, gun positions,

railroads, troop concentrations, etc. Most of the missions scored

excellent results.

Around July 25, 1944 the 394th moved from Chelmsford, England (Boreham Airfield) to the southern part of England, Holmsley South Station near

the resort city of Bournesmouth. The move was to get the group closer for

more flexible air support for the ground forces in France.

By the way, I left out an iimportant part of my military career. When we

arrived in England I was selected to go to an extremely secretive school

to study radar equipment the English invented that may have saved England

from a German invasion. I.F.F. equipment in England could identify German

planes as they left Europe to bomb England. It could identify the type

plane, number of planes and the speed. This invention came at a crucial

time in the war as Germany was beginning its massive attack by air on

England and maybe to follow up with an invasion.

I was sent to Cranwell (home of the R.A.F., Royal Air Force) for five

weeks or so to learn all about I.F.F. (Identification - Friend-Foe). I.F.F.

equipment was then installed in all of 394th air planes. The I.F.F.

equipment was also used to communicate between planes, air to ground, etc.

without the Germans being able to listen in on the conversations. It was a

revolutionary invention at that time.

As mentioned previously, we were moved to France the latter part of August

and lived under combat conditions for the first time. We were on airstrip

A-13 at Tour-en-Bessin, Normandy, France. The abundance of rain and lack

of mail temporarily lowered morale. Most people in the U.S. (outside of

Baltimore where the B-26 was made) didn't know the Marauder from a Piper

Cub. The French people did because we had been bombing German targets for

months before we moved over. They came to the airstrip and yelled: "Vive

Marauder".

Patton was chasing the Wehrmacht (German army) so fast that we moved to

Airstrip r:-59 the middle of September at Orleans, France. This airstrip

was formerly occupied by the Luftwaffe (German elite air force) and before

the war was known as France's "West Point of the Air". However, when we

arrived there it was in shambles as it had been bombed by U.S. planes so

frequently. Also a German general had just surrendered his 20,000 troops

to the Americans and they were walking around Orleans as there were not

enough prison compounds to hold them as they were surrendering so fast.

The Germans continued to retreat and the targets for the B-26 "Bridge

Busters" were out of range so we moved again to A-74 at Cambrai, France.

It was only 25 miles from the Belgium border. While in England our planes

had bombed this airstrip.

Many of us lived in small old houses in Crevecoeur, about one and one-half

miles from the air strip. Ten of us lived on two floors. There was no

running water, plumbing, or electricity in the village of about 300

people. German soldiers had lived in the house before we arrived and had

planted lots of potatoes before rapidly leaving.

I became acquainted with many of the people living in the village as we

were all neighbors. They were very happy to see us as liberators as the

Germans had been there for four years. The villagers said the Germans were

polite and well disciplined but the Germans were the conquerors and there

was no fraternization. One German soldier did fall in love with a peasant

and hid in a barn with the girl's help. However, the secret got out and

the 585th G.I.s captured him -- he was really frightened!

The industry in the area was sugar beets -- which are tremendous. There

were two gentlemen farmers who lived in Crevecoeur in big homes, high

gates, barns, live stock, etc. The balance of the people were peasants

working the beet fields for the farmers. I became friends with many

peasants and very close to one of the farmers. They had no petrol (gas), no soap, no luxuries, few necessities so we had candy and

goodies for the children but traded soap for eggs. We had not seen fresh

eggs since we left Boston. We could get 16 eggs for ivory soap and 20 eggs

for lifebuoy.

We had not seen fresh potatoes since leaving the U.S.A. so we'd fry them

in our skillet over a pot belly stove and crack 10-12 eggs on top of the

potatoes and with a loaf of French bread have a feast. Nothing better!

We were tired of K-rations and the food in the field mess-tent was scarce.

Several days all they had at mess was orange marmalade and bread. I have

no idea who sold orange marmalade to the Army Air Force but whoever it was

made a fortune for they had it on the table every day from my first day in

the Service to my last day.

When I married Nancy I informed her if she ever served marmalade I would

leave her. I actually did not eat any for over 30 years. Just when we

thought that the German war machine was ready to hibernate until spring,

she suddenly struck out with the greatest counter-offensive in war

history. The Nazis lashed out on Dec: 16, 1944 with a major attack at

Ardennes Forest. Thus the 394th plunged back into action.

On Dec. 18th two crews were lost by the 586th and 12 men were killed in a

practicing formation flying. They were new crews. I was involved in

identifying the bodies at the crash site.

The Ardennes battle (Battle of the Bulge) came to a close January 25,

1945. During December and January the :94th flew 384 aircraft and dropped

540 tons of bombs assisting in defeating the Nazis last big effort causing

them to become disorganized and in rapid retreat.

Christmas Day, 1944 was one of much activity but in spite of a big snow

and heavy schedule most everyone was able to enjoy a good Christmas dinner

consisting of turkey and all the trimmings.

On January 28, 1945 The "Bridge Busters" opened the bombing in the

Rhineland. 18 Marauders busted a railroad bridge at Sinzig, Germany. And

on the 29th more bridges were destroyed in Brandscherd, Germany. In

February the planes went beyond the Rhine River.

On "February 16th the group flew the first of 16 leaflet missions to

inform the German soldiers the accurate war news and news where our troops

were. The leaflets were in German. Before this the German people only got

news the Nazis gave them. By this time the war was almost dead but we

still attacked on occasions.

Luring Feb. and March 1945, 60 missions were flown using 1651 aircraft

dropping 2500 tons of bombs on Germany.

On April 8 the "Bridge Busters" flew their first maximum effort since

November '44. This was our fourth maximum effort of the war. 42 aircraft

bombed an oil storage unit in Neinheim, Germany with excellent results as

the dumps went up in bellows of black smoke.

April 12, 1945 was a very significant date. This was the day of the death

of our commander-in-chief of all the United States forces, President

Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It was a very sad day for all the troops. 1~!e

had a memorial service on Sunday, April 15.

On the 14th, the 394th continued the propaganda campaign by scattering 100

leaflet bombs on the Ruhr pocket. Two days later over 90,000 Germans in

the area surrendered unconditionally to the :'alies. On the 15th we bombed

the marshalling yard at Gunzburg, Germany. However, the.271st mission

which later proved to be our final mission,

was a leaflet dropping flight on the dwindling western front on ij,,ril

20, 1945.

There was little doubt that the 394th had seen their last combat flying in

World War 11 as by now the Allies in the west and the Russians in the east

were only a few miles apart. Another factor the range of the B-26 medium

bomber had been exceeded from our base in Cambrai, France.

After 7 months in Cambrai we moved to airfield Y-55 located near Venlo,

Holland -- however, the air strip for the most part was in Venlo, Germany.

The Germans, before departing the field, blew up every hangar and building

thereon.

It was wonderful being in a place where the natives spoke four languages

including English.

This is the story that the local Dutch residents told us:

The Nazi Commander had spent an evening with a local Dutch girl in the

city of Venlo. The following morning she erroneously informed him that the

Allies would be in Venlo the next morning. The commander quickly ordered

the airfield demolished. For this premature order, the commander and 40

other Germans were shot by the Nazi High Command.

All that was left of Y-55 was the runways, perimeter track, road-ways and

the floors of many hangars. This was much more for us to use than at cur

other bases. The entire 394th group, with exception of high staff offices,

was set up in tents. This was the first time the 394th Bomb Group, the

98th Bomb Wing Headquarters, the 397th

Bomb Group and the First Provisional Pathfinder Squadron were located

together. This gave an idea of the immense size of Station Y-55.

Although we knew for several days that the peace treaty had been signed,

the official announcement did not come until May 8, 1945. HALLELUJAH!

HALLELUJAH! V-E DAY HAD COME (VICTORY - EUROPE).

The first tip-off came on before the actual official announcement by a

teletype operator at 98th Wing who gossiped the news with the 394th group

operator. The copy of the teletype went something like this:

Wing operator: "Hey, Joe, didja hear the great news?"

Joe: "Naw, what?'

Wing: "Just heard the news of unconditional surrender by the Germans."

Joe: "No-n-no kidding! Oh baby, I could kiss you if you were here.

That's such good news you can send it again."

Wing: "Hey! Unconditional surrender has just been announced."

Joe: "Thanks, pal, see ya!"

Wing: "Yeah, China, mebbe!"

The official announcement of the German capitulation came through soon

thereafter. There was no doubt the 394th was a sound and successful unit.

Everyone felt good and looked forward to the future.

Whether it be the Pacific occupation, occupation of Germany, or home, the

394th Bomb group had fought its part of the war well.

And so came the end of the mightiest conflict of all times. The Armistice

signed in Rheims, France ended World War 11. Casualties were heavy in

every branch of the service and in every group in the AIR FORCE. The

following statistics were released on the 394th Bomb Group's 13 months of

combat operations. The "Bridge Busters" suffered:

170 men were missing in action, 86 killed in action, 53 men wounded in

action and 25 men injured in action. The group lost 26 aircraft in combat,

23 to enemy anti-aircraft and 3 to enemy fighters.

271 missions were flown in combat, using 9,036 sorties dropping 13,416

tons of bombs.

The months of June, July, August, 1945 were uneventful; a rest home for

men in the group was opened near Lyon, France. Also we were given R & R

leaves to Vichy, France, Paris, Nice and other exciting places before

being sent to ports of debarkations with names of cigarettes. I was sent

to Lucky Strike in Belgium. Since my specialty I.F.F. Radar mechanic was

no longer needed, I was one of the first to leave our squadron for P.O.D.

P.O.D.s were a "calm down from the war" situation. Great food from morning

to evening cooked mainly by German chefs and bakers who were P.O.W.s. Also

you turned in guns, masks, war equipment, etc.

and exchanged your European money into American dollars. An amazing thing

happened at the exchange -- we were able to turn in guilders (money used

in Venlo, Holland). Everyone had bags of guilders while in Venlo but did

not bring any with them for it was worthless in Venlo. There was nothing

to buy in the stores. Like everyone else I left a big bag of guilders with

friends when 1 departed. Ouch! There was a saying in Venlo by the

residents: "Nix in the shops, everything is in guilders".

Anyway it was great to see a few green backs again -- we received our pay

at Lucky Strike in "green backs".

Our trip back on a Merchant Marine ship was much more pleasant and faster

than the trip over on the G.W.G. All branches of the service were

together: Infantry, Rangers, Tank Corps, Quartermasters, Parachutists, Air

Corps, etc. It was one of the happiest experiences of my life -- "the

thrill of coming home".

Oh! I forgot to mention one of the most emotional feelings for me of the

war. After being moved to Venlo the pilot of one of our 585th planes

wanted me to fly back to Cambria with him to check out the I.F.F.

equipment. The flight crew were detained for several hours so I walked to

Crevecoeur, the village I lived in for 7 months. It is 1.5 miles from the

base and it was a down hill grade all the way. Well, one of the French

kids spotted me walking down the hill and spread the word that I had come

back. About 50 people were there yelling "Jean a ici" Jean a ici" "Jean a

ici" --my French is long forgotten but they were yelling and crying: "John

is here". They were all hugging and kissing me as if I had won the war

single handedly.

I was very popular there. I gave the natives most of my rations except the

cigarettes - for eggs exchange and I gave most of my cigarettes away also.

I had friends in the mess tent and frequently would get leftovers and

distribute around Crevecoeur. Also, my

Mother sent me goodies from home which I shared. These people had not seen

good food or sweets for years. I gave them some Hershey chocolate bars and

they made bread sandwiches with them.

That reception in Crevecoeur was much bigger than I received in Petersburg

when I arrived back on November 17, 1945.

The ship landed in Boston the first week of November and by train some of us

went to the Separation Center, Fort George G. Meade, Md. There we had

orientation sessions, given $300. in cash and talks on going back into

civilian life as well as a thorough physical evaluation.

The train ride to Petersburg, Virginia and a happy reunion with Momma,

Daddy, Ray and the twins - Bobby and Jimmy who were one year old when I

left and were now four and into everything. My brother, Ducky was a marine

in the South Pacific and was not discharged until the summer of '46.

It was a wonderful feeling being home again; home cooked food and the

reunion with family, friends and welcoming home other G.I. friends who

were returning from the war almost daily.

Lots of blood, sweat and tears were created by WW II not only, by the

service men but by the families of the men who laid down their lives for

their country.

John W. Buddy Eubank

June 30, 1998

Name: John William Eubank, Jr.

Age: 90

Division: 9 th Air Corps

Group: 394 th

Bomb Wing: 98 th

Squadron: 585 th

Duties: Radar Tech

Trained: Traux, MacDill, Ardmore, Kellogg, Camp Miles Standish

Sailed to Europe: Geo. W. Goethals on 2.27.1944

Arrived : 3.8.1944 Firth of Clyde, Scotland

Embarked: 3.9.1944: Greenock

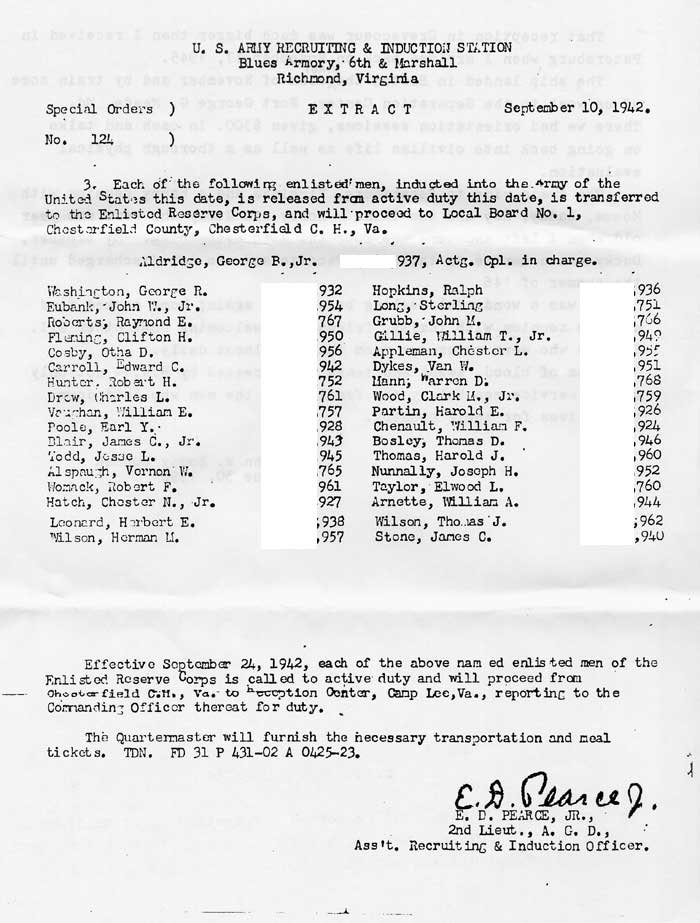

U. S. ARMY RECRUITING & INDUCTION STATION

Blues Armory, 6th & Marshall

Richmond, Virginia Special Orders ) E X T R A C T September

10, 1942.

No. 12)

3. Each of: the following enlisted men, inducted into the Army of the

United States this date, is released from active duty this date, is

transferred to the Enlisted Reserve Corps, and will proceed to Local Board

No. 1, Chesterfield County, Chesterfield C. H., Va.

Aldridge, George B., Jr. Acting Corporal (Cpl.) in charge.

Washington George R.; Hopkins, Ralph; Eubank, John W. Jr.; Long, Sterling;

Roberts; Raymond E.; Grubb, John M.; Fleming, Clifton H.; Gillie, William

T., Jr.; Cosby, Otha D.; Appleman, Chester L.; Carroll, Edward C.; Dykes,

Van W.; Hunter, Robert H.; Mann, Warren D.; Drew, Charles L.; Wood, Clark

M.; Vaughan, William E.; Partin, Harold E.; Poole, Earl Y.; Chenault,

William F.; Blair, James C., Jr.; Bosley, Thomas D.; Yodd, Jessie L.;

Thomas, Harold J.; Alspaugh, Vernon W.; Nunnally, Joseph H.; Womack,

Robert F.; Taylor, Elwood L.; Hatch, Chester N., Jr.; Arnette, William A.;

Leonard, Hobert E.; Wilson, Thomas J.; Wilson, Horman L., Stone, James C.

Effective September 21, 1942, each of the above nom ed enlisted men of the

Enlisted. Reserve Corps is called to active duty and will proceed from

Chesterfield CM, Va. to Reception Center, Camp Lee, Va., reporting to the

Commanding Officer thereat for duty.

The Quartermaster will furnish the necessary transportation and meal

tickets. TDN FD 31 P 431-02 A 0425-23.

E. D. PEARCE, JR.,

2nd Lieut., A. G. D.

Assistant Recruiting & Induction Officer.

|