Home > Guest Book > Historians > Pages & Links > About Us > B26 Site Index

At the 2000 reunion, Colonel Smith delivered an insightful lecture on the intricate process of a B-26 mission:

"Saturday Night Banquet. Colonel Gayle L. Smith was the Headquarters Group Operations Officer and gave an excellent talk on how a B-26 mission in the ETO was received, planned, and executed. He started with target selection, bomb selection, and how the information was passed on to the various groups who held crew briefings, scheduled take-off times, assigned routes to the target to avoid enemy flak batteries, located the Initial Point (IP), set heading to target, determined bomb release, and planned the route back to base."

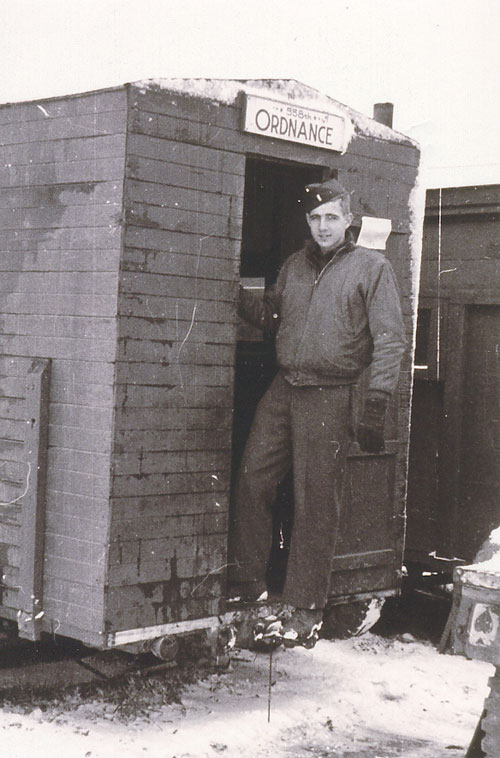

Col. Smith reported on an invitation from the people of Clastres, France (Airdrome A-71) to commemorate the unveiling of a memorial for all airmen who occupied the airdrome. The event, held on October 19-21, 2002, honored French, German, and American forces, including the 387th Bomb Group.

For the occasion, Col. Smith designed a plaque presented by 19 representatives of the 387th. The plaque, inscribed in French, translated to:

"The 387th Bombardment Group (M) AAF, comprised of the 556th, 557th, 558th, and 559th Squadrons, presents this plaque to the citizens residing in the area of Airdrome A-71 during the period from November 1, 1944, to April 29, 1945. They graciously supported our operations, despite the daily dangers involved with storing highly explosive munitions and the constant disruption of massive take-offs and landings. Their understanding, patience, cooperation, and assistance were outstanding. They accepted us as partners in their community and should always be remembered for their contribution to our common goal and ultimate success."

The plaque featured an engraved photograph of Col. Carl P. Storrie's B-26 aircraft.

I sought advice from several individuals on the type of presentation that I should give. They ranged from a Senator John McCain patriotic speech to a "feel good," to a President Harry S. Truman type - "Tell them like it is." I think, in today's political and socially correct society, I better steer clear of President Truman's method of calling an S.O.B. an S.O.B. or his "give them hell" method or the trial lawyers might hit me with a class action suit.

Recent attention to our generation by Tom Brokaw and others has bestowed upon us the label of "the Greatest Generation." It isn't something that we sought, and it, like our participation in WWII, isn't any more than recognition of what we were proud to accomplish. We served a good cause - to regain freedom for many at great sacrifice in lives and injuries. We retained this right for our fellow citizens only to have freedom used as justification for activist disruptive behavior - i.e. the flag controversy; the disruptive behavior at the Seattle World Trade talks, the disruptive behavior at both political conventions. I don't think this is quite the way we felt that freedom would be interpreted.

Our generation grew up facing adversity. We didn't dwell on the fact that we had little. This attitude helped us build character and compassion for those that were worse off than we; this attitude created camaraderie with each other and it overcame adversity. We were proud simply to be just plain American.

Now I'll talk about our contribution in making the 387th Bomb Group a proud contributor to the World War II victory. Those of us serving in the 387th know what we did, so I will be covering some things that you accomplished and never really talked about to your wife, significant other, children, grand children, and yes, even to your great, great grandchildren. I hope that I will even reflect on some events unknown or long forgotten. To those of us who were in the 387th from its forming, we will reminisce. To others we will hear a bit of history.

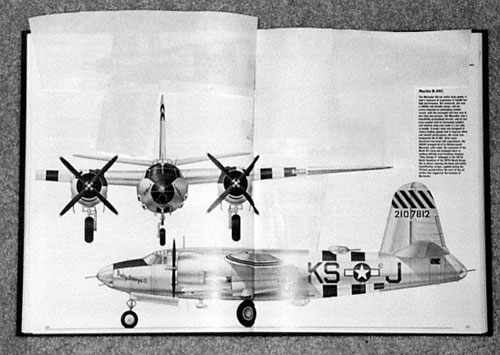

Pictured above is 42-107812, 387th Bomb Group, 557th Bomb Squadron "BABY BUMPS II", 30 May 44 to 2 Jan 45 damaged at A-64 St Dizier, France, repaired and reflew to wars end. Lt Robert W. Fairburn

The B-26 almost never made it. Design began in 1939, well in advance of the attack on Pearl Harbor (Dec. 7, 1941). The initial order for 201 aircraft at $78,000 each resulted in the first aircraft rolling off the line on November 25, 1940 and the first four aircraft being accepted by the Army on February 22, 1941.

The B-26 was a marked change from past bombers. The takeoff and landing speeds were more than twice the speeds of anything flown by pilots out of pilot training. Likewise, maintenance requirements exceeded those in Army Technical School.

The lack of experience was cited as the main cause of the high accident rate. This resulted in such unflattering references as: "the flying coffin," "the widow maker," "the flying prostitute-no visible means of support," and, slightly less offensive references as "one a day in Tampa Bay," or "one a day the Barksdale way," etc.

Along these lines, please permit me to make personal reference to my introduction to the B-26. I had just graduated from pilot training and commissioned a 2nd Lt. (shavetail to those experienced army troops). I was transferred to Barksdale Army Air Base in Shreveport, Louisiana. It was one of those bases where you entered the base down a beautiful boulevard toward a massive masonry control tower inside a traffic circle. Just beyond it was the flight zone that ran perpendicular to the entrance road. It was just dark enough for night flying to begin. As the bus carrying a number of us was approaching the tower, we saw this trail of sparks going down what we later learned was the runway. Well, this seasoned 1st lieutenant that was in charge of the bus transportation, said, "Welcome to one-a-day the Barksdale way." That slogan, along with the others, became more understandable as we were briefed on the reputation of the B-26. (The cause of the sparks-releasing the landing gear too soon.)

This occurrence, along with others, resulted in three different, very formal attempts to cancel the B-26. Hearings reached the level of then Senator Harry S. Truman's Committee in July of '42. The inquiry involved a number of people, but it is widely held that aviatrix Jacqueline Cochrane and General Doolittle were instrumental in saving the B-26. Apparently, Jackie Cochrane, after flying the B-26, said, "Any person who doesn't want to fly this aircraft is a sissy." (sort of sexist in today's political and socially correct society.)

The aircraft I have been showing was taken from David Alderton's book, The History of the U.S. Air Force. The aircraft number and name was then Major Joe Whitfield's aircraft with the 387th tiger stripe. Major Whitfield became the 557th Bomb Squadron Commander shortly after we arrived in England when then Major Charles Keller was returned to the states through medical recommendations. Major Whitfield became a frequent Group and Box Leader and was our "D-Day" Group Leader.

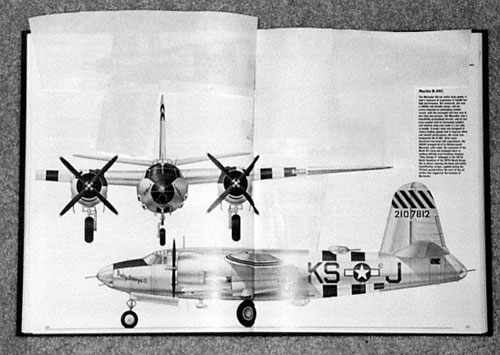

This is Col. Carl R. Storrie, our Group Commander. He was the body and soul of the 387th Bomb Group from January 1943 to VE Day (May 7, 1945), even though he was transferred on November 14, 1943. He was the inspiration for both the enlisted man and officer. The early contact with him was the so-called "hat in the ring" appearance. There were actually two "hat in the ring" meetings-the first one February 2, 1943, when a meeting was called in the theatre. This was attended by approximately 3/4 of the 387th personnel. Another quarter of the total overall strength of the 387th had not yet reported for duty. They were called to a meeting in the fireproof machine room of the hangar.

This group, about 400, including myself, had settled in to the area behind the large metal doors. When the time arrived for the meeting, the metal doors banged as if hit by a battering ram. This really focused our attention on the doors. We could not see Col. Storrie, but this hard-visored hat came sailing into the room. His first and only words were, "My hat is in the ring-is yours?" He meant every word of it. He then proceeded to say that this Group was going to be the best and he expected everyone to believe it.

Colonel Storrie carried this same enthusiastic attitude in training and combat. He wouldn't expect you to do anything that he wouldn't do. He was a believer in everyone doing the job he was supposed to do. He was the boss, and friend, of enlisted and officer alike. If a person needed disciplining, he was the one to do it, but only after he was convinced that that course of action was required. It didn't make any difference whether you were a private or squadron commander. His enthusiastic attitude, work ethic, and inspiration were evident throughout our entire training and combat period. It seemed to me that he had instilled a loyalty among all, and they retained that "hat in the ring" attitude throughout our 2 1/2 years.

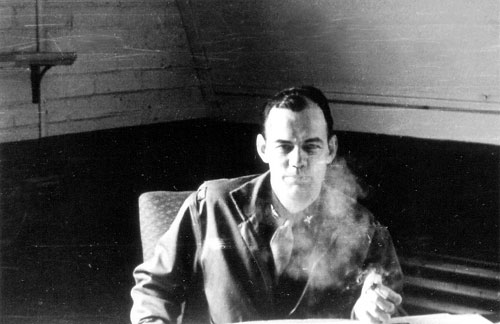

This abbreviated organizational chart is shown to reflect the method of operation. Basically, the S-3 officer (Group Operations) was responsible for developing and scheduling all flight training and combat flight mission activity. Particularly in combat the S-2 (Intelligence) and S-4 (Materiel) personnel at Group and Squadron level worked closely with S-3 (Operations) on every mission.

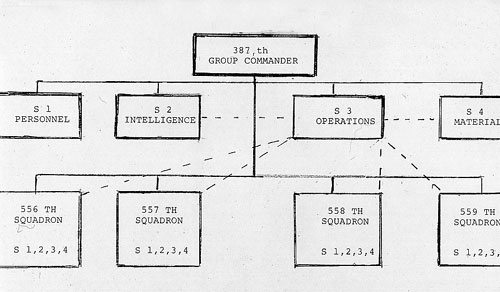

This is the 559th Squadron Intelligence Officer Samuel "Sam" H. Monk. He, along with Bill Engler, the Group Intelligence Officer, was a steadying force in my life. Bill Engler was a WWI veteran, so he was old enough to render sage advice at all times.

I would judge Sam Monk to have been in his middle 30's, and was also a stabilizing force in day-to-day missions. Sam was all heart to everyone. I worked with Bill and Sam in every mission and they left me with the most pleasant of memories, along with their tremendous assistance in mission planning. Gus Shields of the 556th Squadron, Karl Peterson of the 557th Squadron, and Stan Rowe of the 558th Squadron were the other intelligence officers that did terrific jobs in debriefing crews on return from missions.

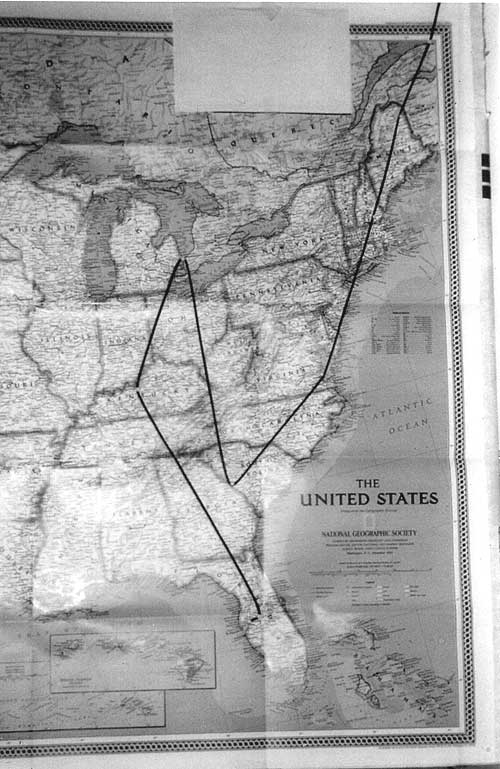

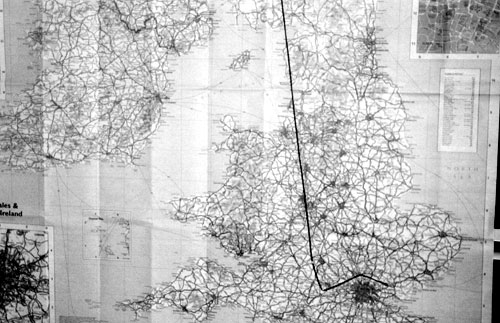

This is the road map of the 387th Bomb Group while in training and in preparation for overseas. We trained at MacDill (Practice Bombing, Night Flying, Instrument Training and Formation Flying) until April 1943. We moved to Lakeland, Florida where we undertook the Low Level Attack Training. The danger involved with low level formation flying occurred on April 23, 1943 when two 556th aircraft collided and crashed.

Several other events occurred at Lakeland: We experienced a shortage of aviation fuel and a decrease in training. On April 29, 1943, all co-pilots were transferred back to MacDill to become first pilots in a follow on group: On May 3, 1943 new co-pilots were on board; Major Phillip Sykes replaced Col. Robert Stillman as Executive Officer. [Col. Stillman left to become the 322nd Bomb Group Commander that was en route to England.] Col. Stillman would be considered a "technocrat" in today's society, but a pleasant one. Before you could say "Good morning, Sir", he would have asked you a technical question concerning the operation of the B-26. Col. Stillman, leading the second low level mission of the 322nd B.G., was shot down along with the entire formation. Seriously injured, he survived, becoming a prisoner of war. [This triggered the change from low level to medium altitude.]

May 11-12, 1943. The group left for Godman Field, Ft. Knox, Kentucky, to conduct air and ground forces training for the next two weeks. Since the Group had departed from Command Control over our training, Col. Storrie, received a written commendation from Command Headquarters citing the 387th for having the best record of maintenance efficiency and overall flight time experienced to date.

May 25, 1943: The Air Echelon, augmented by selected aircraft maintenance specialists, moved to Selfridge Field, just north of Detroit.

The Ground Echelon had applied for an all-expense paid cruise to England on board the Queen Mary. However, the next scheduled departure from New York was June 24, 1943. So, I am told, remaining at Godman wasn't all fun and games. [I have also been told that on board ship canteens were not necessarily filled with water.]

This was our aircraft on the ramp at Godman. I show this for two reasons: First, please note the amount of ramp space used to park just 20 aircraft. When I continue with the route map from Selfridge, visualize the amount of ramp space required at each airfield en route to England to park over three times that number, i.e., 65 aircraft. The second reason I am showing this slide is to correct a misconception that the aircraft were left at Godman and that the Air Echelon traveled to Selfridge by train. All aircraft flew to Selfridge on May 25, 1943. We did not, during training, possess aircraft for individual crew assignment, hence two-thirds of the crews, including myself, had to travel by train.

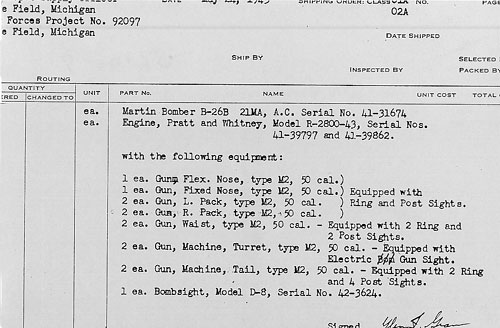

I was given the task (privilege) to assign an aircraft to each crew, i.e., 65, including Col. Storrie's. The pilot of each crew completed this type of invoice. They signed for an aircraft costing approximately $100,000 without any collateral. This invoice was for Capt. Glen Grau's aircraft-one that he had to crash land on returning from a mission. (I doubt he ever received a turn-in slip.) Walter Ives was the original 556th Commander, however, after a few months in England, he was transferred to an in-theatre higher headquarters and then Capt. Grau became the 556th Squadron Commander until close to VE Day (May 7, 1945). He, also, was one of our frequent Group and Box leaders. He led the Second Box on D-Day.

While at Selfridge, each crew test hopped their aircraft-making sure that guns, bomb racks and the aircraft was fully operational. Three events that remain in my memory were two complaints from small fishing vessels on Lake Huron that didn't appreciate being attacked by those pesky, low-flying aircraft; the third event was an accidental firing on the fixed nose guns. The aircraft was parked on the ramp facing the hangar. During inspection and preflighting, according to all people around the aircraft, the aircraft guns just accidentally fired a burst that ricocheted off the pavement, went through the empty hangar doors and out the back side. No injuries were sustained and everyone declared their innocence. There was no time left to find out what really caused it.

<

June 10, 1943

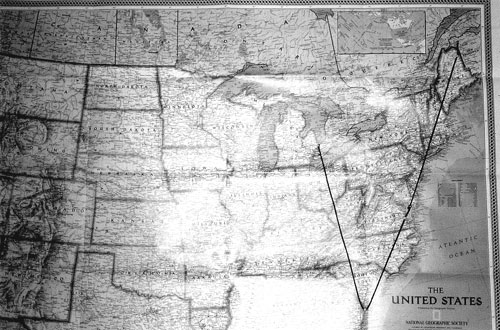

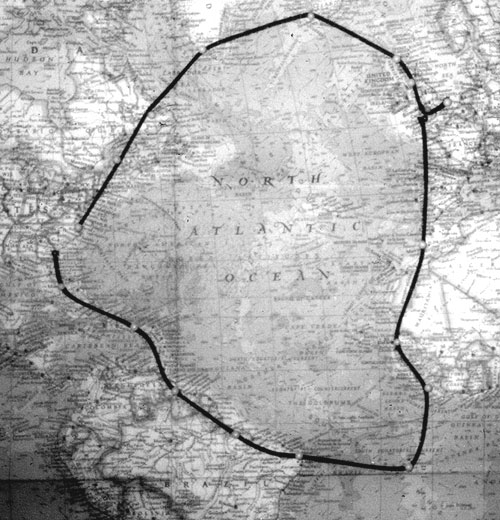

This is our route from Selfridge to Maine. The first stop was Hunter Field, Savannah, Georgia to pick up our personal equipment, clothing, eating utensils, bedrolls, pup tents, etc. Weather en route caused many to land at alternate airfields. All aircraft were at Hunter the following day. Everything was completed by June 14, 1943. Col. Storrie and Capt. Strauss, the Group Navigator, briefed all crews about the northern route.

June 15, 1943

Flew to Langley Army Airfield, Virginia, for clearance.

June 16, 1943

Flew to Grenier Field, New Hampshire. Bad weather prevented us from getting to Presque Isle, Maine.

June 17, 1943

Flew to Presque Isle, Maine and were weathered in June 18, 1943.

June 19, 1943

Presque Isle to Goose Bay, Newfoundland with no alternate airfields available in case Goose Bay closed because of weather. It was a flight of no return.

June 20, 1943

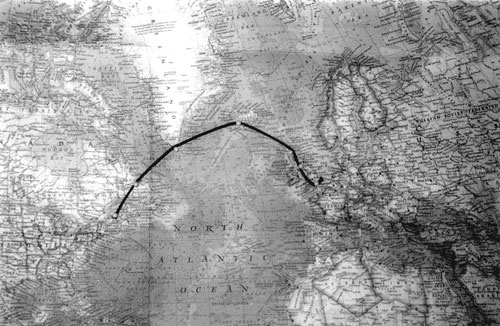

Goose Bay to BW 1, Greenland. The entire Group flew in weather until approximately 75 miles from shore. We broke out into the clear and you could see for hundreds of miles. Icebergs, ice cap were clearly visible. Landing at BW 1 was up a fjord - from sea level up to 168 feet. You had to land because there was no room to turn around for a second attempt. One aircraft was lost in a pullout from a high-speed dive. The aircraft was lost, but every part that could be cannibalized was taken. The crew was distributed among other crews. This was the second flight without an alternate.

June 21, 1943

BW 1 to Meeks Field in Iceland. Take-off was downhill toward the sea, circling back over the ice cap en route to Meeks. Excellent weather with 24-hour daylight in the summer's longest days.

June 22, 1943

This was a day of rest before heading into the changeable weather to be experienced in Scotland and England.

June 23, 1943

Meeks, Iceland to Aldermasten, England. Weather plagued us the entire way and as a result, aircraft were scattered from Scotland to the destination of Aldermasten. Col. Storrie, leading the 558th Squadron, landed in Prestwick, Scotland to refuel and then was unable to reach Aldermasten because of weather, hence landed to the north at the Airfield Brizenorton.

June 24, 1943

Most everyone made it into Aldermasten by nightfall.

June 25, 1943

All but five aircraft skirted London to the north, avoiding the balloon cables, and finding only 4200 feet of usable runway available at Station 162, Chipping Ongar. The US Army Corps of Engineers were building the airfield on a short time schedule, and were still finishing the runway and housing facilities. The first 2000 feet of runway was not available because utility trenches were not closed in. Aircrew members had to sleep in and around their aircraft using pup tents and sleeping bags.

June 26, 1943

The Group Navigator and Z flew to Aldermasten to lead the last five aircraft to Chipping Ongar. On landing, the last aircraft sheared his gear on the open ditch. Luckily there were no casualties. We lost two aircraft, but crews were safe. Arrived with 63 aircraft.

July 1, 1943

The ground echelon arrives so the approximately five-week separation comes to an

end.

This drawing of the airfield at Chipping Ongar was courtesy of Peter Crouchman, a British friend of the 387th. The Crouchman home was near the north end of the runway. The daily noise that we created in dispatching 36 aircraft almost every morning and returning in the afternoon had to require strong nerves by the local residents. They took it wholeheartedly, saying, "This is sure better than the alternative."

These Quonset huts, not fully completed on arrival, were typical of living areas at Chipping Ongar. Larger Quonset huts were used for other purposes.

This is a photo of aircraft on the taxi way prior to take-off (note the condition of the areas around the taxiway and runway). This procedure was normal for every mission, every aircraft and crew were lined up in a specific position that they would occupy in the overall formation.

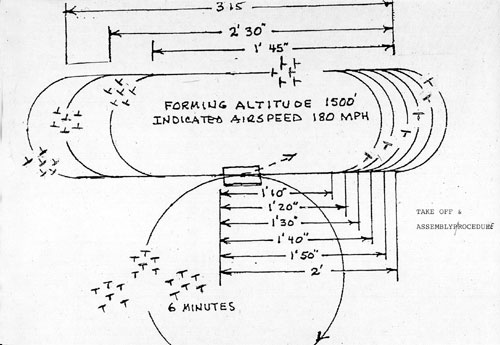

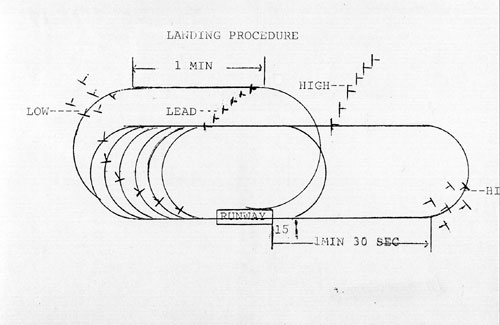

This is the standard take-off, assembly, and flight formation procedure that I had the honor of developing. In England, other air bases were in close proximity, so a procedure had to be developed in order to avoid a conflict with other patterns. This procedure was retained throughout our missions.

Take-off roll, by the lead aircraft began at the precise time [predetermined at the Mission briefing]. A time hack was the last element of any briefing to be sure that start engines, start taxi, and start takeoff roll conserved fuel to ensure a return. All of this was to assure an exact time over the target. Each aircraft followed the preceding aircraft by 20 seconds. If any aircraft experienced trouble on takeoff and had to abort, he fired a flare to signal his trouble to the aircraft immediately behind so that aircraft could either delay his takeoff roll or also abort to avoid a collision.

Forming the six-ship flight and the 18-ship box was accomplished by adhering to each aircraft following the timing into the turns. The second box of 18 aircraft would be exactly six minutes behind the first box; hence, the six-minute turn that allowed the boxes to get into formation.

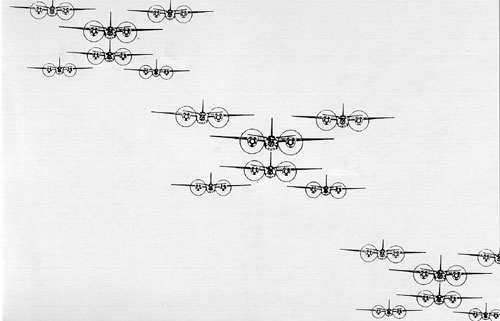

This is the relative position of a box of 18 aircraft. This elevation difference would prevent accidents between flights during turns. Each box of 18 aircraft would fly high and/or low on the other box for the same safety reasons.

This is the standard procedure for landing on return from a mission. Aircraft returning with wounded on board had priority and would drop out of formation to land first. The aircraft, low on fuel, was also given priority. (We had one close call with one aircraft losing one engine and landing with a later determined 35 gallons of fuel). At Chipping Ongar we had to depend on the main runway, so any aircraft with major battle damage that might crash on landing and tie up the runway would be delayed, if non-life threatening.

This single engine practice provided training that would permit the crews to cope with having to fly formation with the loss of one engine from battle damage.

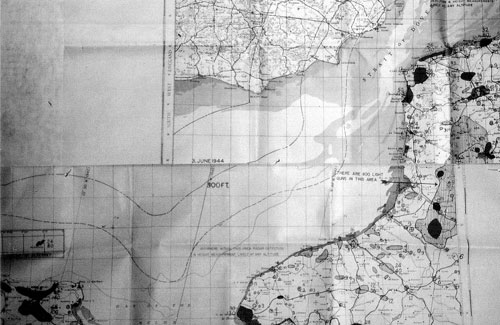

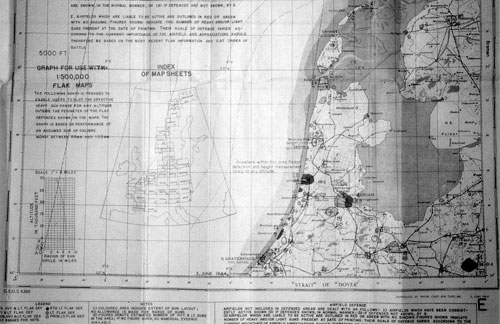

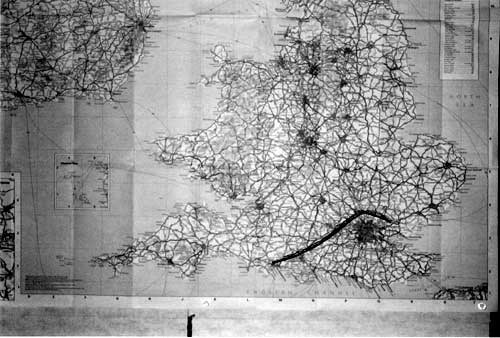

This flak map, of the French coastline and limited interior area, reflects the more permanent installation that we tried to avoid, or that we had to penetrate on the missions. Crew members on debriefing after each mission would continue to verify these, as well as identifying other enemy defenses.

This provides the same information in the Netherlands. Some of the most intense flak would be located around German airfields in the Netherlands and France. A majority of our missions, for the first three months, were directed at the airfields to disrupt the German air capability, and hopefully destroy a lot of their fighters in the meantime. Missile sights on the French coast were also protected with the same intensity.

This was one of the lesser damaging crash landings.

They are really awaiting their aircraft to return from a mission. These aircraft were their pride and joy. It was their baby and they treated it accordingly.

Thomas M. Seymour, Grover G. Brown, Jack E. Caldwell

This photo is the follow on Commanders to Col. Storrie. Col. Caldwell, far right, took command from Col. Storrie. [Col. Caldwell was shot down on April 12, 1944, while leading the group against a missile site/coastal defense site at Dunkirk.] Col. Seymour, left, became Commander, but lost his life in a B-26 crash near Chipping Ongar on July 17, 1944. Col. Brown, center, became Commander through VE Day, May 7, 1945.

42-96246, 387BG 559BS, TQ-H, Missions Flown 14, 14 Jun 44 to 17 Jul 44

On admin flight to Chipping Ongar prior to reaching his destination pilot

reported that he was on one engine.

Passed over the field at Chipping Ongar and appeared to be going round for a

landing on what would normally be a base leg,

lost altitude and crashed into trees and an open field 2 miles south of the

field near Stondon Massey, Essex. Salvaged by 55th Air Service Group 19 July 44.

Col. Thomas M. Seymour Group Commander (Killed in crash)

42-107581, 387BG 559BS, BLACK JACK, TQ-Y, Missions Flown 3, Missing Aircrew Report MARC 3745

26 Mar 44 to 12 Apr 44 flak over Dunkirk right wing blown off, spinning down

tail came off, crashed 1/2 mile off harbour, two chutes seen just prior to crashing into sea

Lt. Col. Jack Caldwell Group commander P; 1.Lts Donald L Standard C/P; Maj Daniel

E Williams N; 1.Lt's Richard C Moffitt B; Frederick Busch B/N;

John R McGhee, Jr FCO; S/Sgt's Irving L Dibble T/G; Pete Hess, Jr. E/G; Valentine

G Frisz, Jr. R/G. (McGhee bailed out wounded and POW, rest of crew killed)

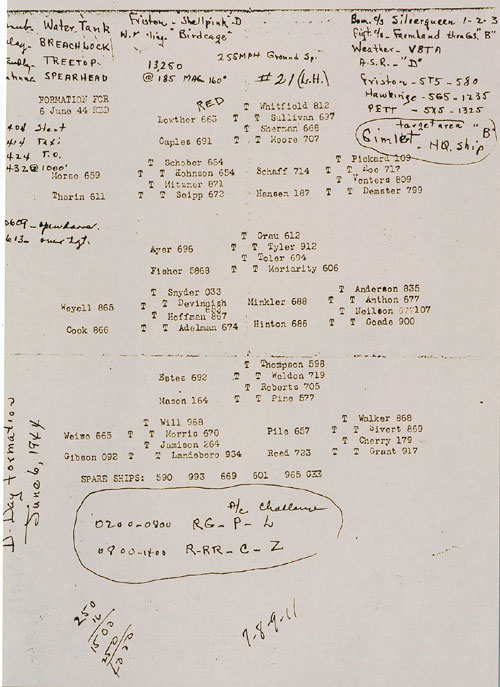

This is our D-Day (June 6, '44) formation against coastal defenses in the invasion area. Then Major Joe Whitfield, the 557th Squadron Commander, was Group Leader; then Major Glen Grau, the 556th Squadron Commander, was the 2nd Box Leader, and then Capt. Bernard Thompson, 559th Squadron, a frequent Box Leader was the 3rd Box Leader.

Briefing began at 2 a.m.; take-off at 4:24 a.m.; time over target at 6:13 a.m. Timing was of the essence as was accuracy on the target. Airborne troops would be behind the coastal defenses; ground troops would be coming on shore. The unusually bad weather forced aircraft to visually bomb at or below 5000 feet--a major departure from our normal 12,000 feet.

Another mission in the afternoon concentrated on bridges, out of the invasion area, destruction of roads, bridges, railroads, fuel dumps were post D-Day targets-an effort to deny German reinforcements to the area. Our last mission at 162 was July 19, 1944 (railroad bridge at Tours).

We moved to Stoney Cross on July 21, 1944-flying our first mission on July 23, 1944 (Railroad Bridge Senguigny). This move provided us the range to cover targets south and west of the invasion area. The airfields, roads, railroads, and railroad yards were continuing targets.

While at Stoney Cross we flew three missions, dropping surrender leaflets in the Brest Peninsula area. Advancing ground forces had cut off the area and German troops were isolated.

Our last mission from Stoney Cross was on August 17, 1944-the Beaumont Railroad Bridge. Two additional missions were planned for August 18, 1944, and August 20, 1944-both were scrubbed.

This shows our route from Chipping Ongar to Stony Cross in July of '44; to A-15 Cherbourg in Aug. 1944; to Chateaudun in September 1944; to A-71 in November, 1944; to Beek, Holland in late April, 1945; and back to France (Amiens area) in late May, 1945.

Our first stop at A-15 Cherbourg saw us continuing to target fuel supplies, transportation facilities, strong points. Our first mission at A-15 was on August 26, 1944 (St. Gobain fuel dump). The last on September 16, 1944 Metz strong point that had to be aborted.

An oddity that occurred while at A-15 was the acquisition of a P-47. The P-47 had the same engine and propeller that we had on the B-26. Shortly after arriving at A-15, a P-47 landed. The pilot told us the engine was missing as he flew across the channel. He walked away and never returned. We didn't try very hard to find the name of the pilot, or the organization to which he belonged.

Well, Mr. P-47 moved right along with every move we made to Beek, Holland. The 557th Engineering/Maintenance section kept it in perfect flying condition.

Our move to Chateaudun, near Chartres, on September 17/18, 1944, was a move to be at closer range to the targets in support of Army ground forces. Our first mission was on September 21, 1944 - the Ehrang Railroad Yards. We continued to target ammunition and fuel dumps, railroad bridges and highway bridges. Our last target, on October 31, 1944, was the Moerdijk Highway Bridge-a mission that was scrubbed.

We moved to A-71 (St. Quentin) northeast of Paris, on November 1-3, 1944. The first mission scheduled was November 4, 1944 against gun positions at Eschweilen. Identification and accuracy were predominant criteria to be followed on every mission to avoid any friendly casualties. This mission was aborted.

The period from early November through December 22, 1944 was one of frustration. The weather, rain, snow, and fog prevented us from accomplishing many missions. During this period we flew 13 missions against German defensive positions; ammo and ordinance dumps, defensive artillery positions, and other strong points. However, weather caused us to scrub 23 missions, and 9 missions had to return with bombs aboard.

It was during this period that the German army mounted an offensive - strafed A-71, and also caused us to be placed on a 6-hour alert to evacuate A-71. On December 9, 1944, we experienced our worst ground disaster. On one of the missions in which we could not identify the target, and had to return with the bombs aboard, one aircraft crashed at the approach end of the runway, catching on fire. Bombs on board exploded, injuring many and killing 29 medics, firefighters and others who exposed themselves unnecessarily. (This figure is controversial.)

The weather cleared briefly from December 23, 1944 through December 27, 1944. We were able to fly seven missions in 4 days against railroad and road bridges, including the Mayen Bridge on the 23rd. The defenses of road and railroad key areas, particularly bridges, were becoming more intense as the ground troops kept closing in on the German retreat.

Weather throughout January '45 continued to haunt us. We were able to fly only 9 missions, while scrubbing 17. Weather began to be on our side starting the middle of February '45. During the last seven days of February '45 and all of March we flew 48 missions in 41 days with only 3 missions that had to be scrubbed. The targets, until the last one in April, were directed at bridges, railroad yards, communication centers, ammo and ordinance facilities, strong points, and defense positions. Our last scheduled mission was on April 26, 1945 - the Schrobenshen Oil Storage facility-the mission was aborted. We moved to Beek, Holland on April 28-29, 1945, and never flew another mission prior to the German surrender on May 7, 1945.

The Final Tally Total

Mission Days 620

Total Briefing Preparations 614

Total Briefings 596*

*18 Preparations Cancelled Prior to Briefing

Home > Guest Book > Historians > Pages & Links > About Us > B26 Site Index