|

|

Guest Book | Pages & Links |

Curtis S. Church, Pilot,

320th Bomb Group, 441st Bomb Squadron

|

|

|

|

Curtis S. Church - FlyBoy |

FlyBoy |

|

|

|

|

Pilot training |

Home from war |

|

|

|

|

Pilot training |

|

|

|

|

|

1st Lt. Curtis Church; S/Sgt. Brosi; 1st Lt. Ambrose Riley; Sgt. Martz; Sgt. Meeker; Sgt. Christianson

Behind Barbed Wire

Curtis S. Church

August 21, 1943

The morning dawned clear and bright (as usual) on the outskirts of Tunis. We

were awakened early and taken to the briefing room for the mission of the day, a

raid on a railroad yard just northeast of Naples.

Nothing unusual about the briefing or the target.

On the flight line the crews assembled and went to their respective planes. Soon

the roar of engines became deafening and clouds of dust swirled in the air as

four squadrons of planes taxied to the end of the runway.

My co-pilot for the day was Lt. Tom Hammond of Seattle, Washington, while the

navigator/bombardier was Lt. Max Rickles of Rochester, New York. The crew was

filled out with three enlisted men; tail gunner, turret gunner, and waist

gunner. Our position in the formation was the last lead flight in a V formation.

The group (320th) was taking off in pairs on dual dirt runways. The noise and

dust increased as the heavily laden B-26s headed down the runways and ultimate

airborne status. Eventually I was waved forward and, with full throttle,

thundered down the field almost lost in the heavy dust that still hung over the

field from the twenty-one preceding ships. Soon we, too, were airborne and, with

perfectly functioning engines, were able to quickly join our squadron formation

and then the group formation. Assembly was routine and we proceeded out over the

Mediterranean toward our target. Out ahead of us was the 319th group of B-26s

(Martin Marauder medium bombers) in similar formation, while 75 P-38s offered

common coverage overhead.

Nothing unusual occurred on our way to our target except our flight leader,

Captain Dobney, lagged back considerably from the group and thus backed up the

following eight planes of his flight. Dobney's element of planes needed a

special surge of power as we crossed over the Italian coastline in order to

catch up with the rest of the group.

We were at 12,000 feet and the view was spectacular. Straight ahead were the

Apennine Mountains; slightly to the right was Mount Vesuvius. Below were

beautiful, white cumulus clouds drifting by, allowing glimpses of the brown

terrain beneath. This serenity was soon to change dramatically.

An occasional burst of flak appeared and mushroomed into a bright orange flash

and then heavy, black smoke. We passed by a fighter field down on the left and

could see the fighters taking off and zooming into the air; trouble was on its

way!

The flak became more intense as we headed further inland; our formation

tightened up as we huddled together for mutual protection. We began evasive

action to throw the ground gunners off. Despite this, we took a direct hit into

our right engine. I feathered the prop and shut the engine down. By pouring more

power to the left engine, I was able to keep up somewhat, but did begin to lag.

Rickles was in the nose preparing for the bomb run when the flak suddenly

disappeared and the fighters were on the scene. They swarmed over us (we

estimated between 45 and 60; later we learned it was 70 or 75) and took runs at

us from overhead and to the rear, diving down on our tail three at a time and

then below and up, blazing at us with machine gun and small cannon fire all the

while. We were well into our bombing run and Max managed to toggle our load. The

group then started a long turn to the left to leave the target, the land, and

back over the Mediterranean, resuming evasive action. The attacking fighters

were very persistent, boring in for one attack after another-they just swarmed

like bees over and around us.

Our fighter coverage had left us to escort the 319th out over the

Mediterranean, but soon returned to give us (the 320th) an assist. In the

meantime, the damage had been done. I called Rickles out of the nose to assess

our damage. I knew that our right engine was out; my side window and windshield

had been shattered and the instrument panel destroyed.

Off to the right I saw a lone B-26 flying parallel but out from the formation

with its vertical stabilizer in shreds. This was only a brief glimpse and who it

was I haven't the slightest idea; I was too busy with my own problems to give it

any thought.

Rickles went back through the radio/navigation compartment to the bomb bay and

quickly returned with the word that the bomb bay was on fire. With our other

problems, Tom, Max and I agreed it was time to abandon ship. I reached up and

turned on the alarm, used the emergency bomb bay door opener, trimmed the ship

the best I could, counted a slow ten to give the crew time to get out, and then

followed out through the bomb bay. Opening the doors had apparently blown the

fire down or out, for we were able to leave via that exit with no difficulty. It

took no second guessing to leave the ship and soon after jumping, I pulled the

cord, the chute rustled out, and after a tremendous jerk as the parachute fully

opened, I was floating in the sky. How calm and peaceful everything seemed after

the noise and violence of the air battle. I was now among the huge, puffy clouds

and I could count the chutes trailing off in the distance, like a row of white

flowers. In the other direction the air battle continued as the 320th proceeded

on out to sea and the returning P-38s mixed it up with German Me109s. I was

later to learn we lost four bombers that day, while the Germans lost twenty-five

or thirty of their fighters. My crew claimed four kills, but these were not

confirmed because we did not return to base.

The serenity of the moment was quickly shattered as a 109 came boring in with

guns ablaze-he was shooting at me! And then another one-and another. No words

could then, or now, describe the shock and fear I suffered in those few moments.

While flying, I was too busy to be afraid, but now I had nothing to do but watch

helplessly as the Messerschmitts attacked me. But one fly-by by each, and it was

over.

Soon, however, I was approaching the ground and at several thousand feet of

altitude I began to attract ground fire. Before long it seemed that anyone on

the ground who had a weapon was firing at me. Huddled in a ball, I pulled on the

shrouds to make myself oscillate as much as possible in order to present as poor

a target as possible. If I was scared before, I was now almost petrified with

fear. I watched with fascination and amazement the trajectory of the ground fire

on its way up to me. I could actually see the bullets in flight! All coming up

in a cone shape, apexing on me!

Suddenly the ground seemed to rush up at me with an incredible speed. Luckily,

my landing was soft as I lit on the side of a conical shaped haystack.

I must have had exceptionally good fortune. I estimate twenty-five or thirty

passes by the 109's while flying, plus ack-ack from the ground, three passes

while in the chute, and intense ground fire from small arms-at least forty to

fifty thousand rounds fired at me or my plane, and I came out of it completely

unscathed. Incredible!

Quickly, I shed my chute and tucked it under the edges of the haystack and my

thoughts turned to escape. A plan of sorts had been developed back at our

base-anyone shot down was to proceed, if possible, to a point of land south of

Naples. On a given night between ten and twelve, a sub was to surface just off

the coast and would send in a rubber boat to pick up any survivors off the

beach. Far-fetched, but it was the only plan I had.

By now it was mid-afternoon of a hot August day in a stubble field on gently

rolling land. Off in the distance was a line of trees that might border a

stream, an irrigation ditch, or possibly a canal. Whatever, it offered a hiding

place until dark, when I might be able to work my way out of my seemingly

untenable position.

Nearby was a peasant's home with all of the indications of occupancy. In another

direction one of the 26s (possibly mine) had crashed tail-up and was burning. An

open field lay between me and the tree line about 1½ miles away. Slowly and

carefully, I began to make my way across the deserted fields. Shortly, it dawned

on me that I was still wearing my bright orange Mae West flotation device that

probably could be seen for miles. Quickly, I removed it and threw it down a

nearby well. Further along, I threw away my web belt and canteen-my .45 had been

left behind in the plane. Soon, I stripped off my throat mike and threw it on

the ground and then realized I was leaving a “Hansel and Gretel-like” trail:

parachute, Mae West, web belt, throat mike.

While crossing the open fields, I was aware of 109s flying above and making

passes, but not firing. They were marking my position so that ground troops

could intercept me.

I had been on the ground possibly forty minutes or so and had just gone over a

gentle rise, down into a shallow hollow and was making my way up the far side

when I heard a loud shouting behind me. Slowly I turned my head only to see a

squad of soldiers behind me, rifles to their shoulders menacingly pointed in my

direction.

With sinking heart-I knew it was over-I raised my hands in surrender and slowly

turned from side to side to show I was not armed. The leader of the squad, an

Italian, gave a sharp order and the rifles were pointed down, except for that of

one soldier who kept up continuous yelling and threatening motions. Gradually

this squad of six Italian soldiers encircled me as I nervously stood with my

arms up.

Was I frightened? Not at this stage. I had used up so much adrenaline in the

past hour or so that there was none left for emotion.

As the soldiers closed in on me, the one who was so angry came up behind me with

his rifle and bayonet at the ready. Roughly, he pushed it into my back, not

breaking the skin, but leaving an indentation that lasted for several days. I

really thought my time had come.

But the sergeant in charge drove my aggressor away with a push and a kick.

Immediately I was patted down for weapons. Finding none, they relieved me of my

escape packet. This contained a map of Italy (in good detail), a small compass,

cigarettes, chewing gum, a D bar (chocolate concentrate), halogen tablets with a

rubber pouch for purifying water, and a quantity of Italian lira, probably more

than these men would see in the rest of their lives.

The afternoon was extremely hot; not only was I exhausted and perspiring, so

were my captors. After the search they motioned for me to be seated, and we all

relaxed a little before our next move. They were eager to try the American

cigarettes (Lucky Strikes) as well as to divide up the money.

They remained fully aware of me as an enemy prisoner, yet were certainly not

unfriendly, and even offered me a cigarette-but not a share of the money! After

several minutes they indicated it was time to move on and so we arose and

continued in the direction of the line of trees. These bordered a deep drainage

ditch. It was easy enough to descend into the fifteen-foot deep chasm; but

getting up the far side was another matter. The slope was steep and by now my

muscles and body were sore and exhausted, sore probably from the sudden jerk of

the opening parachute. The soldiers gave me a hand up and soon we scrambled to

the top.

As we continued along, we passed a large farmhouse surrounded by huge shade

trees and weeping women and children who apparently thought I was going to be

shot by the soldiers. I indicated I needed a drink of water and soon a pail was

dropped into the nearby well and water was drawn up and offered to me. I gulped

down a quantity of cool, cool aqua and was refreshed. I'll always remember the

kindness and warmth of those women and children.

As we continued on our way we entered a small village where we were immediately

surrounded by a menacing group of older men and young boys wielding clubs,

rakes, scythes and other weapons, all intent upon taking me away from my

captors. The soldiers quickly formed a protective circle around me, snapped open

their bayonets, leveled their rifles into the mob and indicated they were to let

us through. There were a few tense moments of confrontation until the sergeant

in charge had the soldiers fire over the heads of the crowd and then immediately

lower them into the mid-section of the mob. A lane opened up and we passed on

through toward a heavily used road that now appeared in the distance.

Soon a military truck approached, braked to a stop and I boarded, leaving my

escort behind. Already on board were the others in my crew as well as members of

other crews who had also been shot down and captured. My crew was all accounted

for, but two of them had received gunshot wounds in their legs. Fortunately, no

vital organs had been struck and no bones broken.

The truck, with military police aboard, continued on its way toward a town on

the outskirts of Naples. Along the way a young medical doctor (army) treated our

wounded as best he could, but little could be done without benefit of hospital

and surgery. The injured later were transferred to ambulances and sent off to

hospitals for treatment. I was not to see them again until after the war.

Before long we arrived at our destination on the outskirts of Naples where we

were temporarily jailed, probably in the local Bastille. We were to spend the

night there in a large cell in the company of mosquitoes and bedbugs by the

millions. We were to find that the latter were a very common phenomenon of

Italian jails and prison camps. In fact, in one camp, PG21, we were allowed to

use blowtorches to burn these voracious, blood-sucking creatures out of their

hiding places. The effort gave us little relief for the little pests bred (or

laid eggs) faster than we could torch them.

Our quarters that first night were not sumptuous to say the least. The cell was

quite large, with a concrete floor, iron barred all around, one single bare

bulb, an open latrine at one end, and raised planks for beds with a cross plank

at one end for a pillow. This space was probably originally designed as the town

drunk tank. We shared these accommodations with the mosquitoes and the bedbugs.

Sometime that evening we became aware of our hunger. We had not eaten since

early that morning back at our base. Breakfast had been three stewed prunes,

toast and coffee served at 4:30 a.m. (Since the fall of Tunis we were on short

rations, because we had to feed the thousands of prisoners we had captured.) By

now it was close to midnight and we could hear our jailers in an adjoining room

playing cards. After a lot of shouting and banging we managed to attract their

attention and indicated by sign language that we were hungry. A considerable

length of time passed before they returned with a stack of sliced brown bread

heavily coated with orange marmalade. Although I detest marmalade, I did eat and

quickly satisfied my hunger. Then began the almost impossible task of falling

asleep-our bed partners were busy all night.

The following morning we were given more bread with marmalade and ersatz coffee

made from ground, roasted barley. The balance of the day was spent in the cell

and being taken to an air raid shelter several times. There were no facilities

for bathing or taking care of our personal hygiene, a situation to which I was

to become somewhat accustomed.

Once, while in the air raid shelter, one of us, Lt. Paul Heimberg, was

approached by an Italian colonel who demanded that Paul speak to him in Italian.

Because Paul was olive-skinned with black hair and deep brown eyes, the Italian

assumed that Paul must also be Italian. We thought this was somewhat amusing,

although we maintained our silence and composure, because Paul was actually a

Jew.

Late the evening of August 23rd, after more bread and marmalade, we were

escorted from our cell by soldiers who linked their arms with us as we walked a

considerable distance to some waiting flatbed trucks. The night was black, which

made the stars stand out brilliantly, and in the distance we could see the

red-orange glow of Mt. Vesuvius. As we walked along, twelve or so of us

prisoners were moved to sing God Bless America and our voices rang loud and

clear in the silence of the night. Even the guards joined in, although they

didn't know the words. What a weird sight we must have been!

Somewhere along the way I suddenly remembered that the 22nd was my wedding

anniversary. The previous day a year ago I was married to the love of my life in

the base chapel at MacDill Field, Tampa, Florida. Only a few weeks prior I had

arranged to have the Red Cross in Ft. Worth, Texas send a dozen red roses to my

sweetheart. I fervently hoped they had arrived.

By early morning of the 23rd we were loaded into the flat bed truck which had

raised edges about 18" high. We were told to stay flat and not look out because

we would be going through Naples, which had just been heavily bombed. Despite

the warning, we did look out from time to time and saw the tremendous damage to

the waterfront with ships sunk and damaged, often times keel-up.

One amusing incident occurred as a tyrolian cap slowly appeared over the side of

the truck followed by the amazed look of a curious soldier who wore it-such

astonishment I have never seen.

The truck soon veered away from the harbor and eventually we made our way

through a long tunnel that now housed refugees from the constant bombings of the

city. On the other side of the hill was a long descent toward another bay. Off

in the distance, we could see the Isle of Capri.

After unloading, we were taken across a long revetment that extended into the

water toward a huge rock. The rock stood up on end like a giant egg. Stairs were

carved into the side. We ascended to the top, which proved to be an ancient

fortification. It was now our temporary place of confinement-infested, of

course, with hordes of relentless bedbugs.

Several times each day we were escorted down the stairs to a large cave dug into

the rock. The occasions were air raids in the immediate vicinity. This was to

become our routine over the next several days.

Food was becoming a problem, because the Italians had made no arrangements to

feed us. However, one evening we were taken back across the revetment to an

Air-Sea Rescue base operated by the Italian Air Force and given a scrumptious

dinner. It was in the officers club; we were placed in a separate dining room.

Soon huge silver trays of steaming foods were being carried in by formally

attired waiters and we were able to eat to our hearts' content-and in style.

This was to be our last good meal for the next twenty-two months.

Our numbers continued to grow as new POWs were brought in-we now numbered

twenty-five or so. Along the way we were interviewed by International Red Cross

people and allowed to write a brief message home-which never arrived. On about

the fifth day we were awakened, taken to the bottom of the rock, and loaded into

a large bus for transport to Rome and beyond.

Food continued to be a problem as we were fed only sporadically and

infrequently. However, for our bus trip we were each issued a day of Italian

rations consisting of several tins of stew and meat with several slices of

bread.

During this period I became aware that I was not feeling well. Soon I developed

a case of diarrhea, followed by nausea. Then my skin and the whites of my eyes

turned yellow; I had yellow jaundice. This was to stay with me until mid-October

and I was to become increasingly more ill to the point that I almost died from

it. Because I could not tolerate the food given me-oily or fatty-I gradually

lost weight and strength. No medication or hospitalization was offered. It

probably was not available.

When the bus was loaded we were on our way to new adventures and experiences.

Beside the driver we were accompanied by eight armed guards, each of whom

carried a leather briefcase, which later proved to contain food and wine for

their personal use. From time to time as they smoked, our guys would bum

cigarettes from them. As we became bolder, when a cigarette was offered we would

take the entire pack and pass it around, much to the amazement of our guards. We

prisoners laughed and kidded and took as much advantage as possible, even to

stealing the food and wine from their briefcases. The guards raised no note of

protest, although they stayed alert so that no escape was possible-it was on our

minds constantly. Probably we could have overwhelmed them, but not without

bloodshed-ours.

From time to time the strong urge of diarrhea would overtake me and I would

indicate to the sergeant in charge to stop the bus to accommodate me. At first

he refused, but with much urging I pointed to his cap indicating I would use it

for my purposes. He did stop the bus and, accompanied by a guard, I was led off

to the side of the Appian Way where I was able to relieve myself. What a sight I

must have been to the Italian motoring public! Stooped down with my pants

lowered and watched over by an embarrassed guard.

Along the way the bus broke down and had to pull over to the side of the road. A

courier was sent back to Naples to send a replacement bus. We waited in the hot

August afternoon but no help arrived. It became apparent that we would have to

spend the night where we were and so we were escorted to a nearby field, which

had just been burned over to get rid of the stubble. In the morning our uniforms

(suntans) and faces were covered by black soot making us rather grotesque, as

well as repulsive, looking characters.

By now I had been in captivity for seven or eight days without any opportunity

for personal hygiene-shaving, bathing, brushing of teeth, change of clothing and

all the rest. In the military the word “rank” is used a lot, and I was.

A tow truck and mechanic arrived by mid-morning and he determined our problem

was a broken rear axle. Our bus was then towed away and soon a replacement

arrived. Again we boarded and continued our journey. My jaundice was still with

me and on occasion I would have to interrupt our journey in the same way as

before, for the same reason.

On one stretch of the road we were high up on a steep slope paralleling the

coast of the Mediterranean. We pulled into a rest area where a stream catapulted

down in a broad, many-fingered fan. It was really a beautiful area, covered by a

grove of shade trees, the cascading water, and the blue Mediterranean Sea

below. Several portable type food shops were near and we were all “treated” to

an Italian type (spumoni) ice cream cone. Because we hadn't eaten in the past

thirty hours, I ate my cone although it did nothing to improve my ailment and

the bus stops became more frequent.

Soon we were entering the outskirts of Rome and before long we were aware of the

Roman Amphitheater and later the Vatican in the distance. We stopped at the

Italian Army Headquarters for a few minutes while our escort logged us in and

got further orders for our disposition.

In the late evening, after climbing up mountain roads, we arrived at a converted

monastery. It was to be our interrogation center and “home” for the next thirty

days. Exhausted from the trials of the last several days, we were escorted to

individual cells where we flopped down on mattresses on the floor and soon fell

asleep.

Early in the morning, I was aroused by the opening of the cell door and handed a

bowl of vegetable soup and a small bread roll for breakfast. As I had gone

without any substantial food for three or four days, I gulped the meal down-only

to pay for it with severe nausea and diarrhea.

My cell was approximately eight by ten feet in dimension, with solid walls

broken only by a small barred window that looked out over a patio area and a

solid door with a peephole that led to an inner hallway. Otherwise the room was

bare except for the mattress on the floor and a dim light bulb suspended from

the ceiling.

It was now my ninth or tenth day of captivity. During this period I had eaten

poorly. I was sick. I had not bathed, shaved, brushed my teeth, washed, and I

still wore the uniform in which I had slept alongside the Appian Way in a

burned-over stubble field. Surely, by smell and appearance, I was ready for

burial.

The days soon turned into a routine: morning soup and bread; pounding on the

door to attract the attention of a guard to take me to the latrine; an exercise

period of half an hour spent walking in the patio; evening meal of soup, bread,

and cheese; and lights out around eight or nine in the evening. The meals were

greasy or fatty. They aggravated my jaundice and its side effects, so I ate very

sparingly and slept most of the time.

One day dragged into another, so that the events became blurred and timeless,

until one morning I was ordered to remove my clothing in exchange for a ragged

but clean Italian shirt and trousers. My clothes were taken for laundering.

Several days later when they were returned, I was taken to the patio area for a

shower and shave. Probably forty-five days or so had elapsed since I last

experienced these luxuries and, though they were simple, they were wonderful.

The shower was merely an overhead pipe that tapped into a natural spring and was

as cold as Siberia. This and a piece of no-lather soap allowed me to at least

rinse away some of the accumulated grime and smell of the last month and a half.

As I stood in the shower, “shivering like a dog passing peach stones,” I was

also allowed to shave with a razor that seemed to have been used by all the

prisoners back to the time of Hannibal. Although my beard was not stiff or

coarse, it was long and, thus, it was torture trying to shave smooth and clean.

But finally the job was done and I really felt refreshed.

Then back to my cell, where I was able to don my clean suntans, before being led

down to the commandant's office for my formal interrogation.

I was amazed by the information they had about me: place of birth, schools,

names of parents, home address, telephone number, flight schools, bomb group and

squadron, name of commanding officer, location of the group, and many other

facts and figures of a similar nature. These facts were intended to impress me

with the extent of their knowledge and lead me to confirm other data that was

interspersed with the accurate information-an attempt to get beyond my name,

rank, and serial number routine.

After fifty or sixty minutes of sparring back and forth, the colonel became

quite angry and dismissed me. He had tried to soften me with kindness (even

offering me an American made cigarette, which I had refused to his

astonishment-I didn't and don't smoke). In turn, he cajoled me, became

buddy-buddy, then confidential, and finally angry when I refused to respond

beyond name, rank, and serial number but asked: "What would you do, sir, if our

positions were reversed?"

All during this period I had been treated decently except for food and

sanitation. For the most part I was left alone, which suited me just fine,

because I felt miserable. The isolation was intended to soften me up for the

colonel, but its effect was to allow me to rest and try to recover.

Several days had elapsed after my interrogation when twenty-five of us were

again assembled and loaded onto another bus. We were transported over the

Apennines to the Adriatic Sea and our prison camp, PG 21 at Chieti, Italy.

Except for exercise periods, when we were not allowed to speak, we had been

separated from one another for the past thirty days. Our trip to PG 21 afforded

us an excellent opportunity to share our accumulated personal experiences.

From initial captivity to the present we were under heavy guard. Although escape

was always on our minds, no opportunity presented itself. Several factors

hampered any attempt:

1. We didn't speak the language.

2. We were unfamiliar with the territory.

3. We were not organized.

4. We had no plan.

5. We were still in something of a state of shock about our captivity; our

thinking was fuzzy.

Later these deterrents were either resolved or became unimportant.

Our bus looped and curved and climbed its way over the Apennines. At one point

we encountered a steep grade into a valley. The driver rode the brakes instead

of downshifting in the American fashion. After a descent of a number of miles,

we entered a small village with our brakes on fire. We pulled into the village

square where the driver used a bucket to douse the burning brakes with water.

The average Italian soldier knew very little about mechanics, perhaps because in

his youth he had little opportunity to work on things mechanical. He was either

from a small farm operated with hand tools or from a poor urban family where

even a bicycle was a rarity. American youngsters had wagons, bicycles, old alarm

clocks, and even old cars to tear apart and reassemble. So our undereducated

driver was really not to be blamed for his ignorance about the operation of his

vehicle-or maybe he was just stupid!

Eventually we arrived at PG 21, a compound with high, thick walls covering

several acres. Guard towers were evenly spaced around the walls. Inside we went

through routine admission procedures. We were checked for contraband such as

escape aids; for example, a small compass tucked into the rectum-a thorough

search indeed!

Nothing was found; my only possessions were the clothes on my back, my shoes,

and an Omega wristwatch that my parents had given me when I graduated from

flight school in August 1942.

Although beset with jaundice, I was finally admitted into the main compound

along with my companions of the last forty-five days. There we joined those who

had preceded us into custody. There were about fifteen hundred POWs. Most of

them were British, taken during the North African campaign. Only several hundred

were American, including a chaplain who had served with the British at Tobruk-Father

Byer from Boston. My POW number was 262, signifying that I was the 262nd

American that the Italians had captured to that point.

One of the first to greet me inside the compound was Lt. Robert Patterson of

Columbus, Ohio, a fellow pilot and member of my squadron. Patterson went down

after the May raid on the airport at Rome. We had met little opposition that

day. However, after turning off the target, well out to sea his ship (he was

flying on the left wing of our lead ship and I was on the right) suddenly veered

off and plunged toward the water. We were at twelve thousand feet at the time.

As I watched, I saw several parachutes and then the ship hitting the water

followed by a widening oil slick. Because the target for that day was an

extended mission, right on the very edge of our range, we had been instructed to

conserve fuel as best we could and loosen up our formation after leaving the

target. Despite these instructions, I followed Patterson down and buzzed the

area. I saw two swimmers in the water. Doing part of a figure eight, I came back

over the area and, as planned, the crew threw out our life raft. We could do

nothing else to assist, so we continued back toward our base in Africa. Because

of low fuel, we had to land at Bizerte to gas up before returning to our base

outside Tunis.

My entry into PG 21 at Chieti was the first any of us had seen or heard of

Patterson since May 1, 1943. We had a great reunion and a chance to exchange

stories. After Bob left the target at Rome everything was going smoothly with no

indication of problems at all. Well out over the Med, Patterson's control cables

snapped and the plane plunged to the water. Although the alarm was sounded only

two of the crew were able to parachute out: Patterson and an enlisted man. The

co-pilot and other crewmembers perished, including Sgt “Red” Baines who had been

a crewmember on the Jimmy Doolittle Tokyo raid in May of 1942.

After a few minutes of struggling in the water, our B-26 flew low over them and

dropped a life raft within a few feet of them before it taking off toward

Africa. At that time, he had no idea it was us, but was extremely grateful for

the help. Swimming to the raft, they were able to clamber aboard and take stock

of their situation. There were emergency rations, but the water cans ruptured

upon impact and the contents were lost to the two survivors.

They were adrift in the craft for five days and six nights until they were

finally washed up on the shore of Sardinia. They were eventually picked up by an

Italian patrol and followed the same path that I was to follow several months

later. Fortunately, they were only weak from hunger, their thirst problems

having been solved by several providential rainstorms.

Despite my continuing illness, I quickly adapted to the routine of prison camp

life. Because the camp was mostly British, we had a British C.O. and daily

events were by British custom. The Italians presided over morning roll call,

followed by “breakfast” at 6:30 in the mess hall adjacent to the kitchen. This

“meal” was composed of a breadroll which was to last the day, and a cup of

“brew” (tea). Later in the morning we were usually served a barley soup and

whatever we wanted as a supplement from our Red Cross parcel, which had been

handed out earlier in the week. Another “meal” was served around 4 p.m., and

another “brew” was offered around 8:00 in the evening. Although it seems we were

stuffing ourselves continuously, the fact is that these “meals” were pretty

sparse. Often they would consist of a fresh fig or two and a small piece of hard

cheese. (Just what I needed with my Yellow Jaundice.) The Red Cross

parcels-mostly from England-were supposed to supplement the Italian food for one

man for one week, but in actuality we were given one parcel for twelve men, most

of which was taken out beforehand by the kitchen crew.

An English parcel consisted of a small tin of oatmeal, a tin of powdered egg,

sometimes a can of bacon or corned beef, hardtack biscuits, a chocolate bar,

boxed raisins or prunes, tea, and English cigarettes. Individually, we kept the

chocolate, biscuits, and cigarettes, while the remainder went to the central

mess.

The inside of the compound was about eight acres in area and surrounded by a

high solid wall with sentry boxes and searchlights at each corner and in

between. These were manned around the clock by armed Italian soldiers. An

amusing sidelight was the practice of some British prisoners. Knowing of the

Italian susceptibility to superstition, they would stand near the wall and stare

up at the sentries. This would make the sentries extremely nervous and they

would complain to their commander.

He, in turn, issued the prisoners an ultimatum-stop or risk being shot. The poor

ignorant peasant/soldier thought he was being given the Evil Eye and feared for

his future.

Included in the compound was an administration building, a small infirmary, a

central building, mess hall, and several large buildings each with several

dormitory bays. Each dormitory bay slept 120 men in wooden bunk beds. Again we

were plagued by bedbugs, which we attacked with blowtorches (loaned on parole)

to drive them from their crevices and cremate them. Their aggravation was

intensified by hordes of flies that seemed to be bent on keeping us constantly

slapping, brushing, and miserable.

Although we were each given an allotment of 100 to kill each day (a task which

could be accomplished within ten minutes) there seemed to be no diminution in

their number.

Our days were spent in roll calls, eating, exercising, slapping flies, torching

bedbugs, lots of sack-time, and talking-I had the added chore of going to the

bathroom about every thirty minutes. Incidentally, the bathrooms were inside and

central to the dorm rooms. They were beautifully tiled in blue and contained a

large vat of water with a pail for flushing and also for showering. The latrine

itself was merely a shallow trough with a number of holes emptying into the

sewer system. A pail of water would serve as a flush. Also the pail could be

used for showering, bathing, and washing clothes.

As mentioned previously, I came into the camp with absolutely nothing on my back

except my suntan uniform and military insignia. Father Beyer, the aforementioned

chaplain, shared his towel with me by simply tearing it in half. Because he had

received a parcel from home that day, he gave me his old toothbrush, which I was

to use (after cleaning it up, of course) for the next several months. The

Italians issued me a large gray wool blanket and a canteen cup, both of which I

retained until the end. These were my worldly possessions.

Because my acute illness persisted, I recall very little of the daily events or

activities of the camp. After several weeks I was moved to the infirmary. It was

manned by some British non-com medics and an American who had one year of

medical school to his credit. There, with rest and a milder (bland) diet, I was

on my way to recovery. Nonetheless, I still had remnants of jaundice until the

middle of December-probably five or six months in all-and there were times when

I thought surely I was dying.

We heard about the landing in Salerno, and that landing craft which were

scheduled to be used in an American effort to liberate our camp had to be

diverted to bring fresh troops to the intense fighting at Salerno.

One afternoon we heard that Italy had capitulated. By early morning all the

guards had gone AWOL and left the camp unguarded. By orders of the British

commander all escape attempts were to be cancelled in anticipation of a rescue

attempt by the Allies. We remained as prisoners for several more days with camp

routine as usual.

On the fourth or fifth day after capitulation, a German unit entered the

compound and took over the camp. We were now German prisoners of war-Kriegsgefangenung.

The sentry boxes were mounted, roll call (appel) was as usual, only under German

supervision rather than Italian or British. Several days later we were rousted

out of bed around three in the morning, as if for roll call. One unit of British

were escorted outside the gates and soon we heard the rat-a-tat of machinegun

fire. Then unit by unit we too were marched to the outside and loaded into

trucks to be transported to another camp inland at Salmona, about 35 or 40 miles

from Chiete.

The machinegun fire was for effect only-and it did its job. No prisoners were

shot and no prisoners made an attempt to escape. The dulling effects of poor

diet, the shock of captivity, the early morning low, and German psychology, all

had their influence on our mental condition at the time. We were quite passive.

Salmona was located inland from the Adriatic in a river valley. It was at the

end of a railroad line running over the Apennine Mountains to the west. The camp

itself was a leftover from World War I. It was in a sad state of repair,

certainly not ready for occupancy. Once again we were down to the basics of

survival. It became apparent immediately that the Germans were not ready for us,

because food and water were in very short supply.

The camp consisted of brick and rock barracks surrounded by barbed wire and

guard towers. There was no central kitchen and each prisoner was on his own for

food and any comforts of life he could find, scrounge, or improvise. Our British

command was in disarray, and the Germans were interested only in keeping us

confined until they could otherwise dispose of or provide for us.

Surrounding us were high craggy mountains that looked dry and arid. Many

attempted to escape by simply crawling under the wire, heading for cover, and

eventually moving into the mountains and going south. Still suffering from

jaundice, I followed, but was recaptured by a roving patrol with dogs. I was

returned to the camp with no consequences. It became obvious that the Germans

did not have an accurate account of our numbers or identities, very unlike their

usual Teutonic efficiency. The following several days were a blur. I recall

little of the day by day events, except for feelings of hunger, extreme

discomfort, and filth.

Early one morning we were marched in small groups down to the railroad yards. We

were loaded into wooden boxcars, called “goods wagons”, about half the size of

an American boxcar. We were locked in, thirty-five to the car, and supplied with

German field rations, but no water. Lack of water was becoming a chronic

problem. Soon all prisoners were loaded and we were on our way across the

Apennines.

We were packed in firmly, but not crowded-at least not as crowded as we would be

later. Robert Patterson and I had paired up and shared what rations we had. A

small, wooden-hinged window was discovered at one end of the car and we soon had

it open. One by one prisoners went through the aperture. Reaching around the end

of the car, they could grasp the ladder and make their way to it. As the train

was slowed by a steep grade or sharp curve they could jump off, go over the

embankment, and hopefully find freedom.

Eventually it was Patterson's turn. He had his few possessions in a Red Cross

box tied securely with heavy twine that he had scrounged somewhere. When he

jumped, I was to toss the parcel after him. Soon he was on the bottom rung. When

the train slowed on the way up an incline, he jumped to the rail bed and I

dropped the parcel in front of him. Running fast from the momentum of the train,

he grabbed the box in a quick swoop and went over the side, rolling and

tumbling. I didn't see or hear from him again until the end of the war, when we

met at Camp Lucky Strike near Le Havre, France.

Next was my turn. I made my way through the exit, on to the ladder, and down to

the last rung. I waited for the train to slow down. It soon did-just as it

pulled into a well-lit train station to take on water. I was immediately

discovered and, with much shouting and excitement, returned to the car. A guard

was posted to ride on top of the next car and the window was securely shut.

Later the twenty-some of us who had not escaped were transferred to another car,

building up its occupancy to almost sixty. This group was mainly British, and

they were busily engaged in cutting a trap door in the floor of their car. Using

a case knife broken off near the handle and the iron heel of a British boot,

they had managed to chisel their way through one of the wooden planks forming

the floor of the car. To their dismay, the first cut put them astride one of the

steel crossbeams of the undercarriage. Undaunted, they started over and

eventually succeeded in cutting their way through enough of the flooring to make

an exit passage sufficient to accommodate a good-sized man.

One by one they lowered themselves through the hole. As the train slowed because

of a grade, they would drop on to the ties while the train passed over them.

Many made good their escape via this means, but it was slow going. In the

meantime others were working on the side door. In time, they succeeded in

opening the door, but the cold wind that entered just about froze us. We were in

mountainous country in late October and poorly clad for such conditions-we had

all been based in North Africa and were clad only in suntans.

We managed to jury-rig an Italian gray army blanket across the opening to cut

the wind. The following morning we were slowly pulling our way into the rail

yards at Florence. We could tell where we were, through the early morning light

and the light mist, because of the distinctive dome of the church that dominated

the skyline of that city. When the train stopped and the guards jumped off, our

open door remained undiscovered until the headlight of an engine on a nearby

track shone on it. A surprised guard raised the alarm.

Again, we were transferred to other cars, half of us in one and half in another.

Our car now held around seventy-five, and we were crowded to the point where

half would stand so that half could sit. From time to time we alternated

positions and somehow managed to survive. Sanitation was becoming a real

problem. We used cans from Red Cross parcels, passing them along to where they

could be dumped out. On later train rides this would become the only way to

dispose of the products of our bodily functions.

As we left Florence, we continued northward, but now stopped from time to time

to off-load for water and personal relief. At one point we stopped at the

station platform of a small village and went through what was a necessity.

Across the way an indignant Italian lady was protesting loudly to her neighbors,

with voice, hand gestures and bodily movement, about what was happening in their

beautiful town-comical as well as ludicrous.

By now the Germans had their act together and there were no more escape

attempts. Guards were posted atop all the cars and in the doorways of each.

Slowly we made our way north, eventually crossed the Po River and passed the

beautiful lakes on the approach to the Brenner Pass. Several days elapsed as we

were shunted from line to line and often sidetracked as German troop and supply

trains passed by, heading south.

One mid-morning we pulled into the rail yard at Bolsano, Italy, the last Italian

city before going over the crest and dropping down into Innsbruck, Austria and

the northern end of the pass. Our train stopped in the middle of the yard. At

almost the same moment we heard the sound of high flying planes and sirens, and

witnessed the guards dispersing to revetments on the edge of the yard. Then came

the roar of 88's firing all around the perimeter. We were under Allied air

attack. Peering out, we could see formations of B-17s moving up from the south

on a bombing run.

This was the first bombing of the Brenner Pass and the target was the rail yard

at Bolsano-and we were in the middle of the target.

Almost immediately we heard the eerie sound of dropping bombs-a frightening

“whoosh,” caused by speed and the creation of a partial vacuum which was

instantly filled-a collapsing sound, very distinctive, which had a shuddering

effect on the whole body. Soon the bombs were exploding all around us. We

managed to kick our way out of our boxcar and went up and down the train

releasing the other prisoners. In the midst of this chaos several cars were hit

or knocked over. At the same time, the guards in the revetments began shooting

at us; probably thinking this was a mass escape.

Max Rickles (my bombardier and navigator) and I made our way across the tracks

and into the city. We took refuge in the second basement of a large brick

building. It was extremely dark, there were no lights, and we huddled together

discussing in whispers our next move. Our plotting was in vain; before long a

German patrol swept through the area and rousted us out. We were taken to the

inner court of a large apartment complex for the balance of the day and the

night.

Our stay in the courtyard was uneventful. We had water, and some German rations

were issued-but bathroom facilities were nil, we had to be escorted to the

street to take care of our needs. The courtyard was paved with macadam and here

we spent the night the best we could with the temperature dropping to freezing.

In the morning, hot water was available for drinking, along with heavy brown

German bread with an oleo spread. None of us had had an opportunity to wash,

bathe, shave, brush teeth, or take care of other grooming essentials or

luxuries. We were a motley looking crew, dirty and disheveled in our un-uniform

uniforms; uniforms that had not been washed, pressed, or changed in weeks.

We learned there were casualties caused by the bombing and the firing by the

guards. If any escaped, we did not find out. Our train and the yard were heavily

damaged, but by the afternoon of the following day we were loaded on another

train and continued on our journey to Germany.

Back aboard the train, we continued climbing up the Brenner Pass with snow

covered Alps closing in on us and the temperature continuing to drop. We were

miserable with cold, fatigue, hunger and other factors. The misery probably

helped us to survive. Numbness set in and blocked out all other considerations.

Survival was number one.

Many chilling hours later we descended the Brenner into Innsbruck, Austria,

where we stopped for several hours, again under heavy guard. There we were able

to wash our hands and faces somewhat, use adequate latrines, and finally, eat a

hot filling ration of thick barley soup-the first cooked food in a number of

days, supplied by the German Red Cross.

We continued on our journey toward Germany and Munich. On the way we passed

beautiful snow covered mountains, forests, meadows, and occasional chalets with

stacks of freshly cut firewood piled neatly on the porches. The contrast between

the neatness, cleanliness, and organization of the countryside of

Austria/Germany and the dirt and disrepair of Italy was dramatic.

Had it not been for the fact that we were prisoners of war and the harshness of

our immediate surroundings, this could have been a scene straight out of a

Christmas card.

We passed through Munich sometime in the middle of the night and proceeded

another twenty miles or so without incident to Moosburg. Moosburg was the site

of Stalag VIIA, a prisoner of war camp left over from World War I. It was a huge

complex, completely surrounded by barbed wire with strategically placed postern

(sentry) towers. Inside, the area was sectioned off into numerous smaller

compounds by more barbed wire. Each compound had several wooden barracks

structures to hold four or five hundred men. The barracks were divided into two

sleeping bays and a wash room in between with a hand pump to draw water. A

separate latrine was in a detached building. Beds were of wood, four tiered,

side by side, and end to end, making sixteen beds in all. Each bed had a wood

shaving filled mattress supported on wooden slats. Not very comfortable, but a

blessing in that there were no bedbugs.

From the main gate we were taken to a shower room where we were allowed to take

a hot shower, our first in a number of days, and were strip-searched. They were

looking for any contraband, such as tools, or any escape materials, such as maps

and compasses. The Germans were again very thorough. We then proceeded to the

individual compounds and barracks.

Inside we met prisoners captured on all the fronts-Russians, Serbs,

Yugoslavians, Poles, Greeks, Indians, and partisans from everywhere-thousands

and thousands of men. Our rations were sparse, consisting mainly of potatoes,

barley soup, and heavy German bread. Red Cross parcels were in low supply and we

received one parcel for eight men.

We (those of us brought up from Italy) were at VIIA for only a matter of days

until we again boarded a train headed north toward Berlin. Instead of boxcars,

we entrained onto third class passenger cars, which allowed us to be seated en

route. Before boarding, we were warned by a monocle-wearing army major that if

anyone escaped, ten would be shot. He was very pompous and showered saliva as he

spoke, making us all laugh and jeer at his words. This, of course, infuriated

him and he turned on his heel and left in a huff.

We rode for several days and nights. Finally we pulled into a siding at Sagan,

Germany, on the Bober River on the border with Poland. The countryside was flat

but contained a dense pine forest. We threaded our way through the forest in a

thick fog for several miles to the campsite of Stalag Luft III, Center Compound.

This was to be my “home” for the next sixteen months.

Before entering the compound, we were held on the outside for a search

procedure, picture taking, and identification check. The Germans again were very

thorough, except they erred when they herded us into an area where there were

several buildings housing offices and rooms, such as mail, dental, and Red Cross

parcel distribution, all manned by British prisoners. They opened windows and

talked to us and at the same time we were able to pass them tools that we had

been able to scrounge at Moosburg. No matter how strict the security was, it

seemed we were always able to obtain contraband materials!

While standing in the detention area, I became aware of someone on the inside of

the barbed wire shouting my name. I looked and saw my best friend, Ambrose J.

Riley, jumping up and down, waving one arm, and shouting at me.

Ambrose and I had gone through flight school together, I was best man at his

wedding, and we were assigned to the same bomb group and squadron. We became

room and tent mates and even flew as pilot and co-pilot together on several

missions. We were both shot down on the same day but he was picked up by a

German patrol while I was picked up by the Italians.

Late in the day I completed the outside checks and was admitted into Center

Compound. Again I had very few possessions: the clothes on my back, a half

towel, a toothbrush, an Italian army blanket, and a canteen cup I had stolen

somewhere-and my good health, for I now had fully recovered from my illness.

Riley and I had a great reunion and he introduced me to Kriegie (short for

Kriegsgefangenung-prisoner of war) life and all of its complications and

routines.)

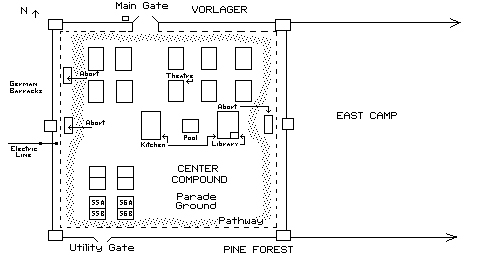

The camp was possibly 12 to 15 acres in area, all surrounded by a double barbed

wire fence with coiled barbed wire in between. About twenty feet within the

inner fence was a warning barrier, a single strand of wire beyond which we could

not go without being shot by a postern (guard). Rectangular in shape, each

corner had an elevated postern box with another in the middle on each long side.

The boxes were manned twenty four hours a day by two soldats (soldiers), each

with a rifle and handgun plus a mounted searchlight. On occasion the outer

perimeter would also be patrolled by soldats, each with a dog. Two gates broke

the fence. The main gate led into the vorlager (utility area) where a number of

buildings were used for camp administration, warehousing, storage, and shower

room (used by the prisoners on a weekly basis). There was also a back utility

gate.

To the east, and adjoining on a long side, was the East Camp where British

noncommissioned officers were imprisoned. In addition to the double barbed wire

fence separating the two camps, there was also a tall wooden fence built in

between to prevent communication-oral or visual-between the two camps.

Within the Center Compound in the southeast area was a large parade ground used

mainly for team athletic programs and appel (roll call). In the center was a

large square pool made of red brick for water storage in case of fire but used

for swimming in the summer and ice skating in the winter. Opposite the pool on

the east and west were two large wooden buildings used for various

administrative purposes but serving mainly as a central kitchen, mail and

parcel distribution, and a camp library.

On the north and west sides in the shape of an “L” were the barracks where the

POWs were quartered; fourteen buildings in all, each holding about two hundred

men.

Encircling the camp just within the warning wire was a walkway used by the POWs

mainly for exercise but sometimes for security in communicating with one

another. On the two long sides stood buildings called “aborts” (latrines and

washrooms).

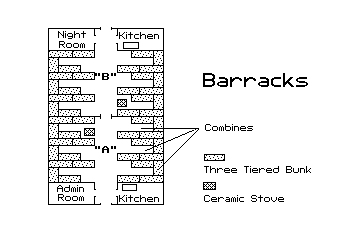

Several of the barracks had been partitioned off into rooms to house six to

eight men each but most were divided into two bays, holding about one hundred

men each. Each block (bay) was divided up by use of bunks into sections of eight

to twelve Kriegies called a “combine.” Each combine had a fuhrer (leader) who

rationed food, made cleaning assignments, and acted as liaison between the

prisoners and their leadership (American). Internally we were organized on a

military basis with the senior American officer as our commander. This was

separate from the German structure of command.

I was assigned to Block 56B, the first combine out of eight in the block, along

with five other officers. I was appointed Combine Fuhrer, a dubious distinction

indeed! Within the block was a large central heater covered with ceramic tile.

It burned compressed coal-dust briquettes for winter heat. An aisle went down

the center. At one end was a door leading to the “A” block, at the other a door

leading to an anterior set of rooms. The interior was dimly illuminated by bare

electric bulbs and four double windows on either side. At the rear and just

outside the door the aisle continued to the back exit door. On one side was a

room used as the night latrine. On the other, there was a small kitchen area

where each combine prepared its own meals.

A typical day would start at 6 a.m. with appel, when we would be awakened by a

bugler playing reveille. After lining up by individual barracks in rows of five,

we would be counted by the Germans. When the count was correct the senior

American officer would dismiss us. Before the count, we would be called to

attention by our own commander, standing at the opening of our “U” shaped

formation on the parade ground. Our commander would then about face and salute

the German commander, who would then order the count to be started. We remained

at attention until our barracks was counted and then stood at ease until

dismissal, when the Germans would salute our officer and then turn and leave the

compound.

Some days would not be typical and the pattern would be drastically changed. For

example, when an escape attempt had been made we needed to confuse, or at least

delay, the count. We would deliberately not cooperate with the count by several

different ruses. One such tactic had the lines of five leaning in opposite

directions and then altering positions in a rhythmic way so that an accurate

count was impossible. Eventually the count would be taken, but not before the

Germans were quite enraged, especially if we laughed at their confusion or

threats.

At other times, particularly if it was cold with snow on the ground, while we

were waiting for the Germans to count our individual barracks, the men would

play horse-and-rider or other active games in order to stay warm. It was really

quite a sight to look across the parade ground and watch grown men participate

in such antics.

An evening appel would be held at five and the same procedure (and antics) would

take place as in the morning.

Occasionally, we would have surprise appels or even “picture parades” in which

we would each pass by a German officer seated at a desk as he pulled out our

identification cards with our pictures. He would compare the picture with the

soldier, ask several questions to confirm identity, and then pass the soldier on

to the waiting formation. These events would take several hours and were very

miserable in winter.

A lot of cooperation took place between the various camps, mostly of a

clandestine nature. This was especially true between our Center camp and the

East camp which was adjacent but separated by barbed wire and a high wooden

fence. Messages would be thrown over the fence at various set times and with

adequate safeguards to prevent detection.

At other times, when prisoners had escaped from either of the two camps, an

appropriate number of men would be sent via a tunnel to stand in for the

escapees so that the count would come out correctly. For example, if two men

escaped from the East camp, Center would send two men as replacements. When the

East camp was tallied and dismissed, the two men would then return to Center

while the Germans were exiting the East camp and coming to the Center for the

counting. This procedure would take approximately four or five minutes, enough

time for the exchange. The men would then stand for Center's appel, the German

count would tally, and the escapees gained more time before they were found to

be missing.

The tunnel between the camps was from abort to abort (latrines), which were the

closest buildings between the two camps. The seats closest to the fence were the

“traps” and the dirt from tunneling was dispersed into the pits, which were

regularly pumped out by the Germans and spread onto nearby farmland. The traps

were appropriately designed so that they could be used without anyone becoming

soiled or contaminated.

Escape was always on our minds, mainly because it tied down a goodly complement

of the German troops assigned to guard the camps. Very few of the attempts were

successful and some were even disastrous; for example, the Great Escape out of

the North Camp of Stalag Luft III. Some eighty British fliers tunneled out and

many were shot and killed by the Germans as they were recaptured. (That story is

pretty well told in the movie The Great Escape, starring the late Steve

McQueen.)

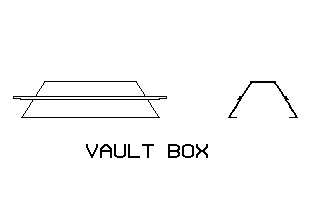

In the East Camp, two British non-commissioned officers made good their escape

by using a Swedish horse (or vault box), a gym exercise contrivance made out of

wood. The box-like device was carried out to the parade ground with two men

inside. Placed over an exact spot, a “trap” was made over a period of time. The

tunnel was made under the barbed wire and out to a forested area on the other

side. Two men successfully made their way to the Baltic and to Sweden where they

were transported back to Britain. The story is well told in book form, but I no

longer recall its title.

As indicated before, escape was a constant, on-going activity in our camp, and

I'm sure in all the camps. We were well organized for such an objective,

starting with an Escape Committee that had to approve all plans for the

attempts. Some people were assigned to camp security. Others were responsible

for making equipment, such as clothing, compasses, documents, maps,

identification, and the like. Others worked on tunnels and plans. Everything

connected with escape had to be done under the constant surveillance of the

German guards.

Much of what was going on was so secret that even most prisoners were not aware

of it. We were instructed (ordered) not to pay attention to anything going on

that seemed unusual; just continue with our routine so as not to call attention

to the activity.

Escape usually involved tunneling from a barracks, under a fence, and into a

wooded area adjacent to the camp. A trap (door) would first have to be made. In

addition to being undetectable, it had to be easy to open and close. Usually

traps were made by lifting a stove from its base or tilting it to one side. Then

a hole could be chiseled through the concrete base. Earth then had to be dug out

to a depth of eight or ten feet before the tunnel could be started.

Once the tunnel was underway, it would need shoring up from place to place

because of the sandy nature of the soil. Bed boards from our bunks would be

“requisitioned” so that instead of having 10 or 12 boards we would be down to 5

and would be barely able to hang on to our places. Later we used flattened Red

Cross parcels to fill in for the missing boards-and even later we used the metal

straps off the Red Cross crates in a criss-cross pattern to eliminate the boards

altogether.

Dirt disposal was always a problem. Its telltale light or fresh color would give

away the digging activity. It was mainly disposed of on the parade ground where

constant activity of games and such would quickly mix it with the old topsoil.

From the entry room it would be placed in socks. Prisoners would suspend these

dirt-filled socks from a girdle arrangement around their waists. They would then

walk out onto the parade ground, slip their hands into their cut-off pants

pockets and untie the knots at the toe of the socks. The sandy dirt would empty

out and be scuffled into the soil.

Between the barracks was an area that we used for vegetable gardening. When the

need arose, we would lift the topsoil, empty the tunnel soil into the garden,

and cover it back over with the topsoil. Sometimes we would dump the dirt into a

volley ball court when an active tournament was underway. Other times some of

the dirt would be dumped down into a latrine which would later be pumped out by

the Germans and spread onto their potato and cabbage fields.

As tunnels progressed, a trolley system was worked out using boards for rails,

rope for towing, and tram wheels made out of bed boards and the bottoms of cans.

A ventilating system was devised by fitting cans together to form a pipe and

using an air pump made of boards and canvas from duffel bags. This forced air

contraption would support the man at the end of the tunnel and his

illumination; a candle made from a can, margarine, and a rag wick. As time went

on these tools became increasingly sophisticated and we were even able to tap

into the camp's electrical system for better illumination.

In Center Compound we never had any successful escapes by tunnel because they

were always discovered before they were ready for use. Either we would become

careless, or the Germans would find them in a periodic sweep. I often felt they

were also playing a game, allowing us to stay busy on such projects until it was

time to close in on us just before the big breakout.

A number of methods were employed to obtain equipment, tools, and supplies for

our escape efforts. Guards could be bribed with American cigarettes (which had a

powerful appeal to them), chocolate, or coffee - all of which came in Red Cross

parcels. Another method was sometimes used when a repair crew entered the camp

with a horse and wagon. A diversion would be created, such as a fight between

two Kriegies (prisoners). Bystanders would contribute a lot of yelling and

excitement, distracting the workers' attention long enough for other POWs to

steal tools, wagon lanterns, and other things loose on the wagon. For the most

part though, we just converted things at hand into what we needed.

Many other methods of escape were attempted; clipping through the wire at night,

going hand over hand along the main electrical line during a heavy snow storm,

riding out on the garbage wagon, and others. None from our camp succeeded in

gaining their freedom for more than a few days.

The penalty for attempting escape or other misdemeanors was a period of time in

the “cooler”, or camp jail. Toward the end there was such a backlog of people

waiting their turn that the whole system became meaningless. Besides, “cooler

time” was like a luxury: food was served to you, you had a room to yourself, the

cell was warm, and there was a peace and quiet unknown in the main camp.

The ingenuity of the POWs was remarkable. They came into the camp with nothing

but the clothing they wore. They were given a paillasse stuffed with wood

shavings, a mattress cover, one bed sheet, a blanket, eating utensils, and food

supplemented by Red Cross parcels. Everything else the Kriegies made for

themselves out of whatever material was available. These were mainly made from

items salvaged from the Red Cross parcels; such as metal from cans, solder from

Argentinean corned beef tins, cardboard, and metal strapping. They also used

materials stolen, “borrowed”, or obtained through bribery, from the Germans.

For example, the metal from tinned food containers was formed into utensils and

tools with which we cooked and ate. One of the food items in an American food

parcel was a can of powdered milk, called Klim (milk spelled backwards), the

size of a typical one pound can of coffee. The top and bottom would be cut off,

and the side split at the seam, making a flat rectangle of metal. The lateral

sides were curled back and over to form a narrow slot; this was done by using a

straight edge of our cook stove and a hand-made, wooden mallet. A thin strip of

metal was then cut from another metal strip by using a narrow slit on our mess

tables and a regular metal knife used for eating. This strip of metal was then

shaped laterally into a letter “C” and slipped down the sides of two larger

sheets already shaped as previously described. Then, gently tamping the curled

edges down, a watertight seal was made.

A number of sheets would be thus clamped together and finally closed together to

form a circle for the sides of the pot being made. A bottom would be made and

shaped to the size of the pot and then soldered to the sides with solder

salvaged and saved from the drops of solder used to initially seal the cans.

Dishes and cups were similarly made and later even time clocks were made from

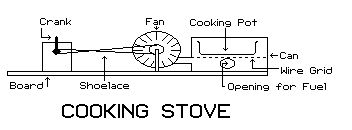

the metal saved from cans. Still later, when we arrived back in Stalag 7A at

Moosburg (near Munich), where no cooking facilities were available, we made

forced air burners from metal, wood, and a shoelace. These latter devices were

very efficient to boil water or cook food in very short order using splinters,

twigs, paper, or any other solid fuel we could scrounge.

The following is a picture of the device:

In time we became quite adept at using the materials around us to make the

things that we needed. A section of the Wright-Patterson Museum in Dayton, Ohio

is devoted to these devices made and used by the prisoners of war. The

Kommandant of Stalag Luft 3 also kept a collection of Kriegie handiwork. It is

surprising what can be done with a few simple materials, tools,-and imagination.

Food was usually on our minds, especially when we were on short rations. A

Kriegie doggerel poem highlights this quite vividly:

I dream as only captive men can dream

Of life as lived in days that went before,

Of scrambled eggs, and shortcakes thick with cream,

And onion soup and lobster thermidor;

Of roasted beef and chops and T-bone steaks

And turkey breast and golden leg or wing;

Of sausage, maple syrup, buckwheat cakes,

And chicken broiled or fried or a la king.

I dwell on rolls or buns for days and days,

Hot corn bread, biscuits, Philadelphia scrapple,

Asparagus in cream or hollandaise,

And deep dish pies - mince, huckleberry, apple,

I long for buttered creamy oyster stew,

And now and then, my pet, I long for you.

Besides “housekeeping” (making up our beds, sweeping, and cooking daily meals)

our most common activity was “walking the perimeter.” One lap around, just

inside the trip wire, was probably _ of a mile or slightly less. Rain, snow, or

shine, we went four or five laps two or three times a day. We usually walked in

groups of three or four, chatting about events, or the war, or home, or recent

letters, or ___.

Ambrose Riley and I usually walked together, along with several others, even

though we were quartered in different barracks. Either he would drop by to pick

me up or I would go by his quarters for him. Ours was probably the most solid

friendship of my life. Later, as a fireman in Rochester, Minnesota, Ambrose lost

his life when he volunteered to go under the ice in an attempt to rescue a child

who had fallen into a frozen river.

Once a week we could go on “shower parade” (and more often if the line was

short.) A line formed every day beginning at 10:00 a.m., at the main gate (and

about every half-hour until noon) and then we marched under guard outside into

the “vorlager” area to the shower room. In the summer time we would be pretty

well stripped down except for our towels, but in winter we went out in our “long

johns.” The shower room, which could accommodate about fifty men, had a concrete

floor and about 25 or 30 showerheads. It was operated by the “shower fuhrer,” a

German non-com who took his work seriously; two minutes of water for a wet down

and then water off and time for a soap down. Then water back on for a rinse off

for two minutes. For two or three American cigarettes he could be bribed to let

the water run for five or six continuous minutes. And then a dry-off and a march

back into the camp.

Washing our clothes was especially difficult, particularly in winter due to the

bitter cold. All of our socks, underclothing, shirts, and trousers had to be

laundered from time to time, even though most of us had no change. We had no hot

water for laundry, so, of course, we had to use cold. We seemed to have plenty

of the so-called G.I. type bar soap that was strong and usable in cold water.

Off would come the trousers to be laid flat upon a table in the wash room, where

cold water was run over them. They were soaped, scrubbed down with a stiff

brush, thoroughly rinsed, and then hung out to dry. And so with our other

articles of wear. Because of the intense cold, sometimes clothes didn't get

washed, or only one article at a time was laundered. It was a common sight to

see someone doing his laundry with his great coat on. I mention all this to

indicate that personal hygiene was important, although at times a chore and a

problem.

At first the Center Compound of Stalag Luft III was a mixture of Allied air

officers from all over the world. But as more and more Americans were shot down

and captured, (because of massive day-light bombing raids), the camp became over

crowded and the other Allied airmen were moved to a new compound, leaving only

Americans in the Center Compound.

At this time, Colonel Delmar Spivey became the senior American officer and

organized the camp according to American military regulations. Beards were

banished, Saturday morning inspections were instituted, and, all-in-all, the

entire camp and personnel were spruced up.

Life in camp settled down to a routine with little variation. We were awakened

at 6:00 a.m. for roll call, followed by breakfast, consisting usually of barley

mush with milk and sugar, and coffee. A few minutes were usually devoted to

sweeping, cleaning and bed making before we took our first laps around the

perimeter. Then, time for personal needs and grooming before we participated in

other activities such as sports, library, classes in our Kriegie University,

more perimeter laps, or “sack time.