|

|

Guest Book | Pages & Links |

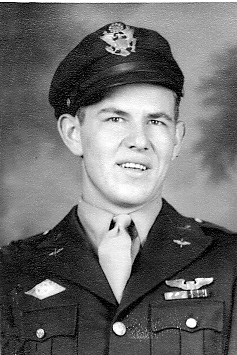

Benjamin "Ben" W. Hicks, Pilot, 65

Missions

387th Bomb Group, 558th Bomb Squadron

WORLD WAR TWICE (Part 1) by Ben W. Hicks

Prior to the United States’ entry into WWII, “War to End All Wars,” President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was frequently quoted, the quoter striving to copy FDR’s famous accent: “I hate wah; Eleanoah hates wah; ouah children hates wah.” But hatred wasn’t enough to prevent the USA’s involvement. Pearl Harbor changed the world on December 7, 1941.

Every veteran of World War II has his or her private memories of the conflict, each memory often times more important only to the individual. Given the persona involved, it is understandable that any recollection of those traumatic times for this survivor usually ends with these lighter moments:

The exact date is unimportant; it was probably in the summer of 1942 that O.B. Johnston and I gravitated from Dyess, Arkansas to Memphis, Tennessee to enter the Army Air Corps. We were transported to Tullahoma, Tennessee to receive all sorts of indoctrinating information, clothing and assorted gear. There I met Ed Hill from Millington, Tennessee. He was a “Slick Willie” from the city, about five feet four; I was a country bumpkin about six inches taller. Strangely, we hit it off and were inseparable for much of our (early) training. After we were issued our gear we changed into the GI (Government Issue) clothing and were told to go start a fire in a barracks number something or other and then sweep and mop it real good. We toted our stuff to the barracks, a torrential downpour began, and we put on heavy coats topped by rain slickers in order to keep warm and dry while we were performing our first duties in the Army Air Corps. It was then that several new raw recruits (probably “rawer” by twenty minutes than we) came into the barracks, and it was then that “Slick Willie” Hill showed his leadership abilities (remember that our raincoats would have covered any insignia or stripes): “Corporal” he said to me, “get two of these GI’s to building a fire and put the rest to sweeping and mopping. And make them windows shine!” he ordered, adding that he had to go to headquarters. Well, the new “Corporal” said “Okay. Sergeant” and started barking orders. It was very fortunate that the new recruits had a sense of humor when Ed came back without his stripes and they also discovered that there was also no Corporal’s insignia on my sleeves.

In a few days we went to Biloxi, Mississippi for basic training, then to Chicago, Illinois for instruction as radio operators. I left Ed in Chicago and went into the Aviation Cadets. Ed was later killed in the Pacific while serving as a Radio Operator in a B-24.

Basic training at Keesler AFB, Biloxi, was probably no different from basic anywhere else in the US except the weather was hotter than in many other places and we were near the Gulf of Mexico. The heat and humidity didn’t bother young people very much and the Gulf did not either: it was off limits anyway during our stay there. What bothered many in our unit was the refusal of one trainee to take a shower when he returned to the tent that was our home. We started calling him “Filthy McNasty” to his face; still no showering. After exactly three days of this the word went out and when the stubborn one returned one afternoon, he got a basic “G.I Shower” with strong soap and brushes. After that he washed assiduously. Well, a least regularly after that!

Shortly after our arrival at Chicago—we were quartered in the Hotel Stevens. This is where our Radio School Training would be located and conducted. The next day we had our first morning roll call. This was to be held in the hallway, after we had made up our beds, all the chrome fixtures in the bathroom glistened and the mirrors were spic and span. All would attend that roll call dressed in the proper attire-shirt, pants, socks and shoes-all except one “O.B.” “O.B.” answered his first roll call dressed in pants, shirt, necktie and blouse (coat) but barefoot. He said that he didn’t have time to put on his socks and shoes. That afternoon he had his head shaved. It didn’t matter that it was in the dead of a very cold winter in Chicago. “OB” said, “combing hair took too much time and was just too much trouble anyway!”

The “dit-dah” days began. We started learning Morse code and it wasn’t long before I would silently translate into Morse Code every sign we passed while marching in formation along the Chicago streets. When we did close-order drill within the confines of Soldier Field, I would spell out in the dit-dah language what I thought of those requiring our marching in knee-deep snow. Several weeks before graduating from the school I applied for Aviation Cadets and was accepted. It was probably a good thing, because although I was transcribing 30WPM I had never learned to assemble a “five-tube super heterodyne” xxx @&*%@x*x radio. When I finally did finish assembling one, it just wouldn’t work and doubtless, I would have failed the course. What a stupid chance I took one time, when I took another cadet’s Morse Code examination (he couldn’t handle the code, like I couldn’t handle the radio assembling). I turned in a perfect paper for him, and two days later took the same test for myself and turned in a paper that was not perfect - and never did understand why the (same) instructor failed to recognize my ugly face.

My Aviation Cadet class was labeled 44-A, meaning that we would graduate in the first month of the year or in January 1944.1 was sent to Montgomery Field, Alabama for Pre-Flight and it was the last class to undergo hazing by upperclassmen....what we suffered, we could not later dish out. Primary training was in Stearman bi- planes at Carlstrom Field near Arcadia, Florida. Remembered for the sulphur water that smelled like rotten eggs and tasted worse. I remember my primary flight instructor who was the lovable N.A. Otto, who instructed me in acrobatics. I lived in horror of having to spin an airplane solo then I learned later that spinning an airplane to the ground was the quickest way to lose altitude when we wanted to get into the traffic pattern and land. I found a reason to actually like it.

Arcadia was also remembered for the WOCs—the Washed Out Cadets that were my friends but whose area of expertise evidently lay in fields other than piloting an airplane.

Our basic training was at the Greenwood (Mississippi) Air Force Base in BT-13s, the famous Vultee Vibrator. Some planes vibrated more than others; one cadet on his first solo flight became so un-nerved with the shaking that he bailed out and was dismissed from the program. I thought I would also be similarly dismissed the time I started taxi-ing to take off with the pitot tube cover still on, but unfortunately I was forgiven after I memorized verbatim the account of a fatal crash when one cadet left the cover on the pitot static tube and since no airspeed was indicated on his instrument panel, he stalled out on his approach and crashed.

Junior McKaskle brought my Papa from Dyess, Arkansas to Greenwood to visit me and they thought I was pretty “hot stuff’ when I got permission to take them out to the flight line and photograph them with the airplanes close-up. When graduating time came every cadet it seemed wanted to go to single-engine Advanced Flying School so the Air Force adopted a unique, singularly scientific method of determining who would go to twin engines and who would fly single engines. A deck of cards was provided, cadets marched by the deck two by two, and whoever cut the highest card went to single engine. Anyone who believed in fatalism could dwell on that ritual for quite a spell.

The low card I cut sent me to Beechcraft AT-10s twin engine flight school at Columbus, (Mississippi) AFB. Advanced Training started November 10, 1943 and ended just before “graduation” on January 5, 1944. Weather during December was rarely conducive to flying and the cadets were encouraged to “pad” their flying reports in order to get in the minimum number of hours. The almost two months at Greenwood were fairly uneventful. I do remember flying over Dyess, Arkansas one day (when the cadet flying co-pilot said okay) and buzzing my hometown. I also remember flying co-pilot for a cadet one winter night when we flew to Biloxi and on the way back the carburetors iced up. After receiving permission to make a straight in approach to the field (no pattern) this would make it a no-no downwind landing. He came down over the field, then racked the AT-10 up on one wing into a vertical position and spun the aircraft around 180 degrees and made a landing into the wind. That was the night arthritis started in mv lees! I thought that I would never get my knees to quit knocking! Just thinking about today... does it again!

(To be continued in the August 2002 Newsletter as Ben Hicks continues his exciting war adventures)

WORLD WAR TWICE (Part 2) by Ben W. Hicks

(Editors Note: In the April Newsletter Ben tells his story as a “young country

bumpkin from Dyess, Arkansas who joins the service because of the Japanese sneak

attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called it, “The Day of

Infamy.” It changed everyone’s lives and the world. Ben signed up and went to

Radio School, then qualified to become an Aviation Cadet. He chooses not to

relate the unhappy situations, but to tell those stories let reflect the lighter

moments, incidences, and the little adventures along the way during his war

years. To continue this story in Part 2 Ben is an Aviation Cadet in Advanced

Twin Engine Flying School where his last paragraph is worth repeating again).

I also remember one training flight where I was flying co-pilot on a cross country to Biloxi, Mississippi and returned. It was cold, black winter night. On the way back the carburetors started icing up and the engines were complaining. Getting back close to the airfield, the pilot radioed the tower for permission to make a straight in approach ( forget making a pattern around the field). He received the “Affirmative,” but our current heading to the airfield would make it a no-no downwind landing. My pilot dropped down in altitude headed straight down the runway for it’s full length and when he reached the end, racked the twin engine AT-10 up on its left wing tip into a vertical position, spun the aircraft around 180 degrees and made a landing into the wind. That was the night arthritis started in my legs. I thought I would never get my knees to quit knocking. Just thinking about that again today...does it to me again!

Another unusual thing stands out like there was a cadet in our Advanced Class named Johnny Fuchs, pronounced “Fukes,” but nobody ever called him Fukes.

There was also nobody at my graduation to pin on my pilot’s wings, but I survived. After a few days delay en route spent at home, I reported to Shreveport, Louisiana where I was assigned as a co-pilot to a B-26 twin engine Martin Marauder crew.

February 15, 1944 was the first B-26 flight with Robert Brockett, Pilot, at Lake Charles (Louisiana) AFB. The “bombagator” (bombardier-navigator) was Warren Butterfield. Bob at that time was married; Betty was as cute as a speckled pup. She and another pilot’s wife got into the habit of arriving on the field each day shortly after we landed and hugging and teasing Bob’s country-boy co-pilot (me) just to watch him blush. That lasted until one day the big co-pilot grabbed both of them in a bear hug and smooched their lipstick all over their pretty faces - no more teasing after that - and no more bear hugs!

Our training ended April 23rd 1944. The crew was sent to Hunter Field, near Savannah, Georgia to pick up our new B-26 Martin Marauder combat plane. After two flights to calibrate instruments, we flew the Northern Route to the European Theater of Operations (after layovers at Fort Dix, New Jersey and Bangor Maine). We were assigned an ATC (Air Transport Command) navigator and made stops at Goose Bay, Labrador then on to Greenland. We were briefed to fly over the icecap but the airplane would not achieve the required altitude. So back down the fjord we went, around the southern edge of Greenland. The navigator took frequent sightings and kept reassuring us that we would have enough fuel to reach the Greenland Airfield. He was right - and that was the last time we landed an airplane on its gasoline fumes. From Greenland we flew to Scotland, then to Warton AFB near Bishop Stratford, England. Subsequently, we were sent to Toome, Ireland for further combat formation training.

Before we went to Ireland, someone in the Squadron slipped up and we (our crew) were advised that we would go to London-town for three days R &R. We, of course, were briefed on every step and after arriving by train we all got in a big taxi for the ride to the hotel. There was no chattering, just rubbernecking, and I felt like somebody should say something and asked the driver how far it was to the hotel. This was the first time I had heard an Englishman say anything, and it sounded like he said “thirty miles” (I learned later that distances were reckoned by the price of riding a bus or a trolley. He said, “It was a three-penny ride only” but it sounded to me like “thirty miles.” I replied: “Aw. it ain’t that far, is it?” and he exploded, “You know and you awsk me!”

All the way across the Atlantic we had heard about the joys and pitfalls of “Picadilly Circus” in London. It is a circular intersection where in the center is a “Statue of Eros” the Goddess of Love and where ladies of the night ply their trade around the circle. A commodity for sale that was sometimes referred to as a “quickie.” After we got settled in our room, Ralph Craig (our radio-gunner) and I decided to check out the attractions. London was practically in total blackout after four years of German nightly airraids. There was virtually no light, excepted for slitted beams coming from vehicles in the streets and similar slits at the intersection traffic lights. We were slowly walking along in the gloom when a young English miss - she was nearly five feet tall -edged up and inquired, “can I do anything for you, sir?” Suddenly, I let out a very loud growl - more like a guttural animalistic shriek, right up in her face. She let out a frightening, sharp squeal to high heaven. A nearby British Bobby rushed over and yelled, “What goes on here? What goes on here?” Craig and I slipped behind a kiosk in the black shadows and doubled up with muffled laughter while the policeman tried to locate the source of all the shrieking noise in blackness.

On May 30, 1944, Robert Brockett's crew returned from Toome, Ireland and we were assigned to the 558th Bomb Squadron of the 387th Bombardment Group (M) at Chipping Ongar, England. They started flying bombing Missions on Railroad bridges in preparation for D-Day. Then there was the night before D-Day Normandy when they systematically took each aircraft during the night into the hangars and painted three invasion stripes on each aircraft’s wing and around the rear fuselage. The group flew missions to the Normandy invasion beaches and area. The German lines were forced to move back and on July 18, 1944 to keep the tactical medium bomber group closer to the enemy lines, a move was made to Stoney Cross Airfield near the Southern Coast of England.

The German’s were pushed entirely out of Normandy, so on 27 August ’44 the 387th Bomb Group, Ninth Air Force, moved to the Cherbourg Peninsula. The group operated from Maupertus, Site A-15, a metal mesh landing strip previously used by allied single-engine fighters and prior to that German aircraft. Our 558th squadron was bivouacked in an abri vacated by the retreating Germans.

Among the assorted paraphernalia issued prior to moving across the English Channel were English-French translation booklets containing a variety of situations. French tykes followed us around as closely as we allowed and when a couple of kids ventured into our new quarters, I pulled out the booklet, pointed to one and reading from the booklet ordered: “Venezici.” He came to me. I pointed to my cot and said “Assayez-vous la.” He went over and sat on the bed. “Hey guys,” I said to my bunkmates, “this really works.”

I found out later, after the group had moved on September 19, 1944, site A-39, to Chateaudun which was South of Paris, that my French translation was not all that good and could lead to problems. Our tents at Chateaudun were situated in the middle of a wheat field and we built wooden sidewalks in order to keep out of the mud. A Frenchwoman and her daughter, about 21, would come periodically to pick up laundry and one day I was going into my tent when the daughter came along and said something in French which I reckoned had to do with washing clothes. I intended to tell her to wait on the sidewalk (“Attendez vous ici”) but without consulting the booklet I said “Venez avec moi.” When I got inside the tent I realized that I had told her to come with me, which she did. When she got my laundry and left the tent her mother began screaming at her in French. I learned later that some of the French people had strict rules against fraternization, with either Germans or the Allies. I learned this after I saw the young mademoiselle the next time. Her head was shaved as punishment for “fraternizing” in my tent. I felt bad about that, mainly because she had not done anything to deserve such treatment. C’est la guerre!

The 387th B.G. moved again to be closer to the front lines so on November ’44 they took over the airfield at Clastres, designated Site A-71, near St. Quentin, France.

Jim Benton was Dick Gunn’s bombardier. Jim was from Louisiana. He spoke Cajun French very well. One afternoon after our morning mission Jim and I were walking down a street in St. Quentin and noticed an attractive young lady on the other side of the street, window-shopping (which even in wartime France was still a popular pastime). Jim says, “Let’s go over there and you ask her where she’s going.” I says, “You ask her - you talk the language. “Jim said, “I’ll tell you what to say and you ask her” (one of us was bashful and it wasn’t I) I said “okay.” He said just say “Ohh Allay voo” (which I learned later at the University of Arkansas when my minor was in French) was spelled as “ou allez-vous?” Well, we crossed the street and walked up to the girl and I had full command of the situation and spoke: “Pardonnez-moi, mam’selle; ou allez-vous?” She was more in command of the English language than I was in French. She replied in beautiful, clear English, “Not with you!” She was only 16 years of age and was going to the nearby university to learn to be a farmer. We also discovered that she was not going to “allez-vous” with us. No way! Period! End of conversation! Good-Bye!

Dick Gunn’s co-pilot, Richard "Dick" Ainsworth, was from California who apparently got in on one of those card-cutting decisions mentioned earlier (about single engine vs. twin engine school) at any rate, he was also a co-pilot in a B-26 twin-engine bomber. He constantly wished aloud that could have been in fighters. Any time a fighter landed at one of our air strips and he was anywhere nearby, he would always rush out to talk to the pilot and look over the beautiful fighter aircraft.

Dick had early informed the 558th Operations Officer Major Lewis R. Sheen that anytime he needed a copilot for a mission he was available. He would volunteer for extra missions so he could quickly achieve his required 65 mission tour and go back to the States for a P-38 Fighter school assignment. He was eager and did finish his tour of 65 missions early and was sent home. That’s the last I heard from Ainsworth. For all I know he might have become an “Ace” in fighters. (Editors note: The dream never happened! Dick returned to the States and found all fighter training schools full and closed to new prospects. There was even an assigned pool full fighter pilots waiting around for overseas assignments.)

Next to Dick Ainsworth desire to be a fighter pilot was his love of poker and eating ice cream. Once he walked two miles to another base when he heard that some ice cream had been delivered there. Being from Southern California, Ainsworth didn’t know very much about snow. Along about the middle of December snow fell on A-71 and at least two good things came about: we didn’t have to go hit the Huns and your young Southern Arkansas lad who lived in the same tent made a helmet full of snow cream (we usually had some scrounged canned milk and sugar) in the tent. I was lapping it up pretty good when Ainsworth entered our humble abode and wanted to know what I was eating. “Ice Cream,” I replied. His yell could have been heard a quarter-mile away. He was quite a cusser also: “Where in the blankety-blank! @#$%&* did you get it?” “Actually, Dick,” I replied, “I made it - it’s snow cream!” Well, he had never heard of such a thing after I described the ingredients he ran outside for a helmetful of snow and began eating it and wishing we had some flavoring like vanilla or strawberry or .. .’’Just think of the possibilities if we had lots of flavoring!” he exulted. Yes, Dick! Yes! yes! yes!

For three days the boys ate nothing but snow cream—then the sun came out and the granular snow-ice melted. Fin!

Ainsworth was also quite sympathetic. The inside of our tent was usually covered with ice when we arose each morning, at least until someone lighted the space heater (if we had any wood or coal), but he would also cuss a blue streak and wonder how in the world the “blankety-blank infantry bastards” could stand the terrible weather without a tent over their heads.

When our crew arrived in the ETO (European Theatre of Operations) the tour of duty for B-26 flight crews were 50 missions. Before I reached 50 the tour was changed to 60. Before I reached 60, Guess What? It had been extended to 65, and before I got to 65, guess what? The War Ended! My last operational mission was on April 18, 1945; the target was the railroad yards in Newberg, Germany. It was my 63th mission. On May 1, 1945, the 387th Bombardment Group (M) moved from A-71 near St. Quentin, France to airstrip site Y-44 Beck, Holland near Maastrich.. The airfields code name was “Dark Gray.”

There was a Captain (his name escapes me) in our Squadron from North Carolina and everyone knew when he was in the traffic pattern. “Dahk Gray, this is ship numbah so-an ’-so; ah ’m a-fixin ’ to turn in on the base laie.” Then: “Dahk Gray, ah’m a-fixin” to turn in on the approach” When we moved from one base to another we forgot about the Weights and Balances scale and just threw everything into the bomb bays of the airplanes. We’re talking about tents, stoves, trunks, furniture, luggage - anything we couldn’t leave without and could jam in. When we moved to Y-44 this Captain from the Tarheel State turned on to the approach and dumped his flaps and something—somebody said later that it was a parachute -fell out of the waist gunner hole at the rear of fuselage and the chap in the tower got all excited: Ship number so-and-so, something just fell out of your airplane!” The pilot remained imperturbable” “IVav-ul Dahk Gray, Ah cain’t so back foe’ it naow! Can I?”

I received the news that the war was over from two Dutch girls. A friend and I were walking back to the base from a small town nearby when they came along on bicycles and (they spoke excellent English) told us how to say “The war is over” in Dutch: it was something like “Der orlog ist gedun. ” We got on their bicycles, the girls sat on the luggage racks behind us, and we pedaled back to the village and went “round and “ round the square yelling “der orlog ist gedun!” (Or something like that) Then we went to the home of one of the girls and her father brought from the cellar some real ancient cognac. We toasted each other and everything else we could think of, and “der orlos” in the European Theater of Operations was finally “sedun!”